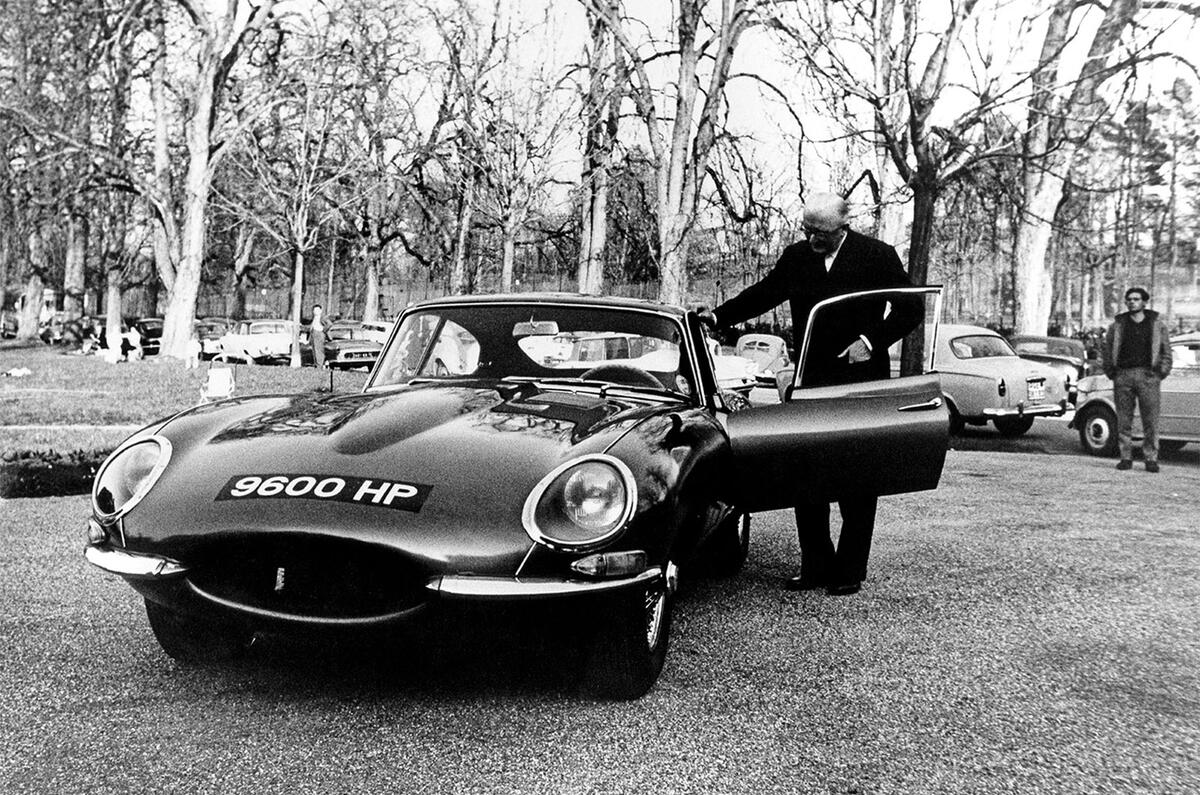

Plenty of stories about great car heroes turn out to be based on sand, but the one about Ian Callum finding his future career with his six-year-old nose pressed against the showroom window of the Edinburgh Jaguar dealership, Rossleighs, most definitely isn’t. His indulgent grandfather had taken him 80 miles from home in Dumfries just to see the extraordinary new E-Type sports car – and the rest is history.

That experience famously encouraged 14-year-old Callum to write to Jaguar boss Bill Heynes, who politely and correctly suggested he study design. Callum still has the letters and eventually followed the advice, finding a variety of car design jobs after graduation and eventually progressing to the top design job at Jaguar – where he not only redesigned every model, some several times, but also created a portfolio of new ones.

Then last year, he left Jaguar to launch a Warwick-based design studio with three partners but under his own name, promising to tackle car and non-car work. The studio’s first big job is a hugely detailed design upgrade, just launched, of the original Aston Martin Vanquish, a Callum original from the late 1990s.

“My grandfather used to get Life magazine, and it was my reaction to the famous photograph of Sir William Lyons and a grey metallic E-Type coupé on the back cover that encouraged him to take me to see the car in that Edinburgh showroom. If I hadn’t seen that E-Type in that magazine on that day, I’m not sure my life would have been the same.

“When I saw the E-Type in the flesh, it seemed to me that the future had arrived. It was so different and perfect and so utterly beautiful. I’d never seen beauty like that before. It was the exaggerated proportions that affected me, long before I realised that this was what the car’s designers, Malcolm Sayer and Sir William Lyons, were playing on. Little old British sports cars – and even the Porsche 356, which I also loved – all had more normal proportions. But the E-Type seemed so special, and it’s still special today.”

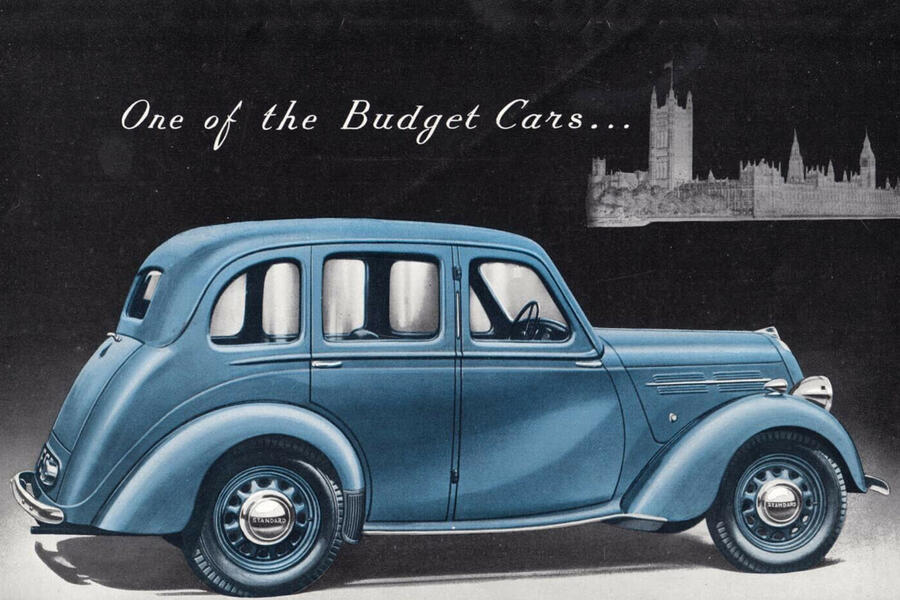

Callum’s father, a solicitor, wasn’t a car man, but it was still a big day in 1960 when the family acquired its first car, a pre-war Standard Flying Ten, although it didn’t last that long.

“Its arrival was a source of fascination for me,” Callum recalls. “I was already drawing lots of cars, and I can remember being fascinated by the curves of the Standard’s front wings. I used to climb on top and slide down them, which my father didn’t like. And I was fascinated by what I saw as the sporty rake of the rear. It wasn’t a sporty car, but it looked good to me.”

Join the debate

Add your comment

Pride

Sundym wrote:

Why are you proud of this man? Simply because you share the same nationality.

This illustrates the dangers of nationalism. In outline it is the danger of identifying oneself with one group against another group. That's how wars are started.

Did his designs work for

Suggestion

Get Carter wrote:

Good idea. The more this type of fawning articles appears, the more one wonders whether in the actual car reviews the author isn't doing his mates a favour.