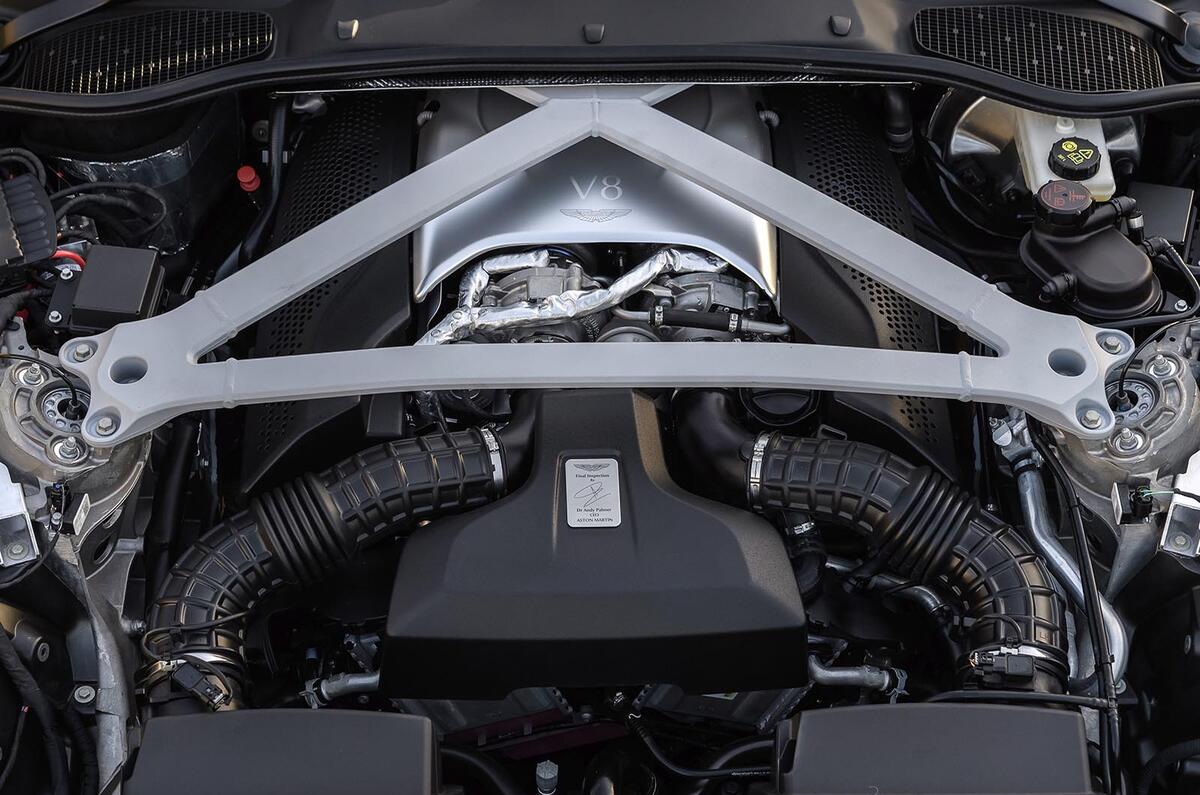

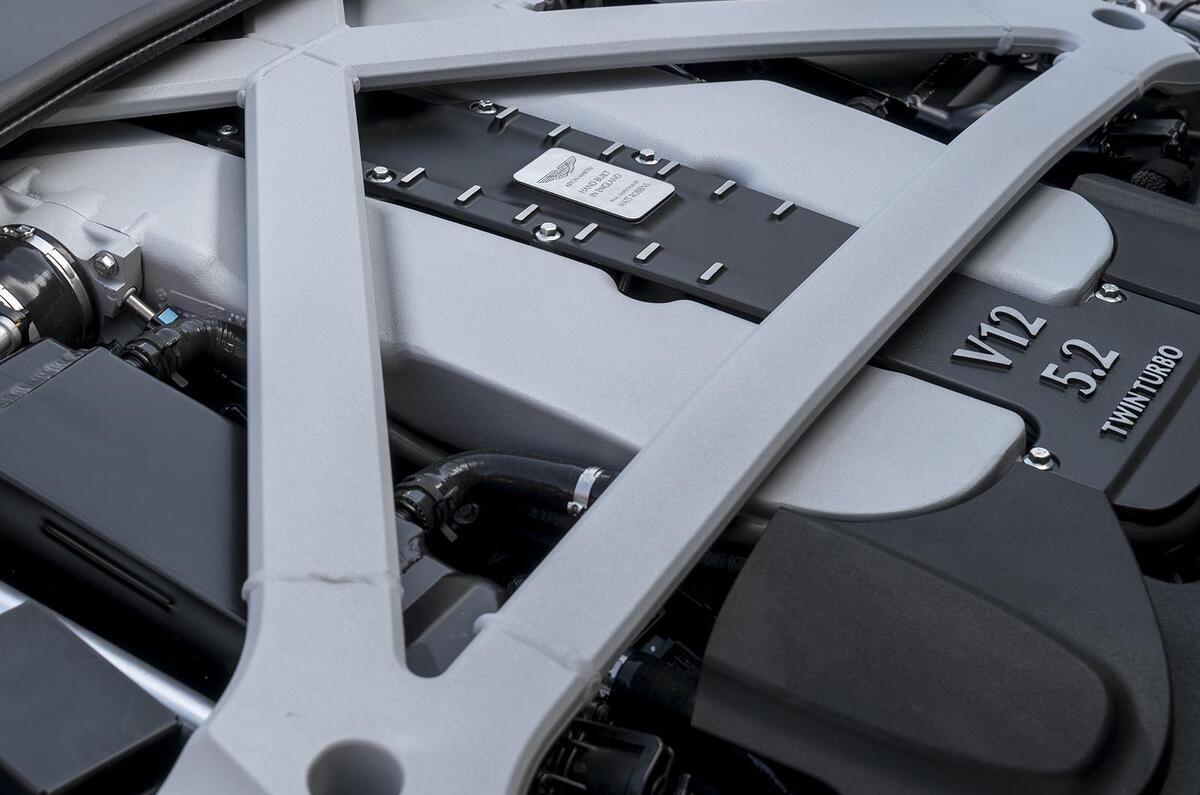

So, the new Aston Martin DB11 is now available with an engine not made by Aston Martin, but Mercedes-Benz.

Aston Martin may be able to tune it a little to produce a bespoke power output or sound, but these are relatively minor mods that affect in no way the truth that this is someone else’s engine. The question is: does it matter?

To me, the answer is emphatically that it does not. The truth is that engines are abominably difficult, expensive and time-consuming things to design, and most small sports car companies simply don’t have the resources to do it (and even if they did, they’d be much better off spending the money elsewhere).

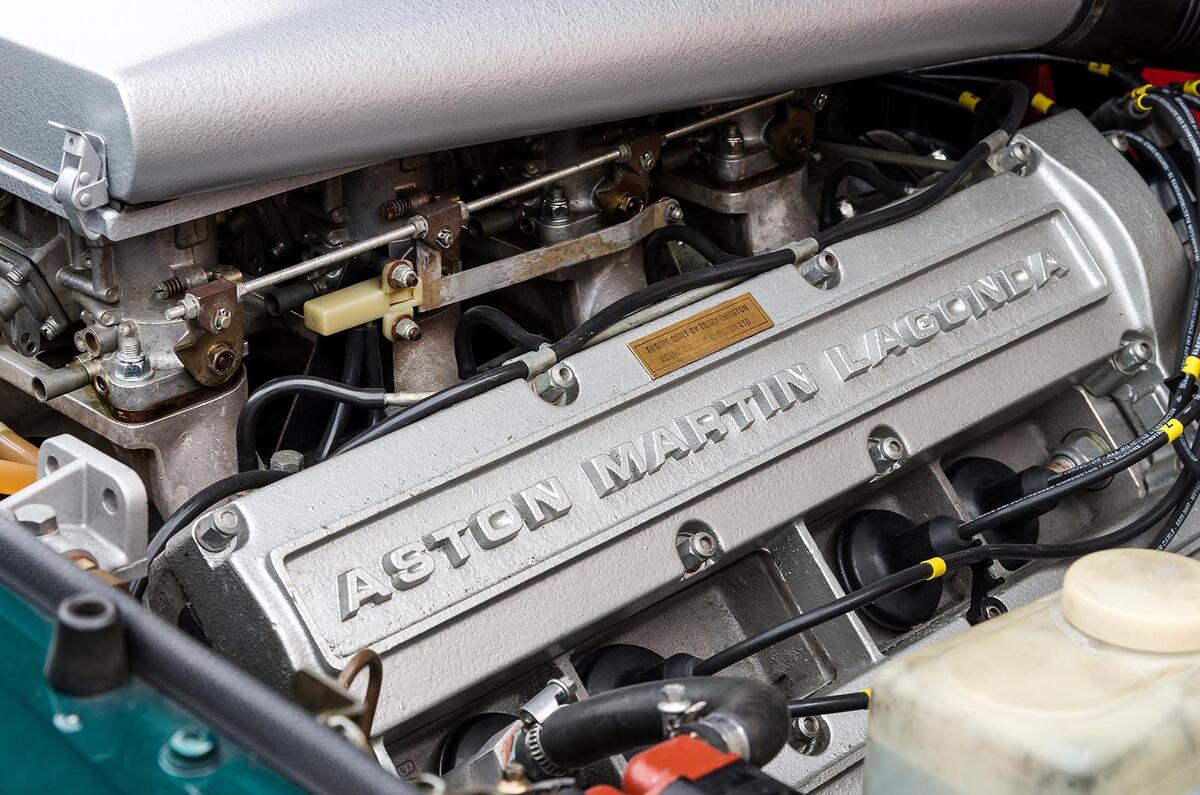

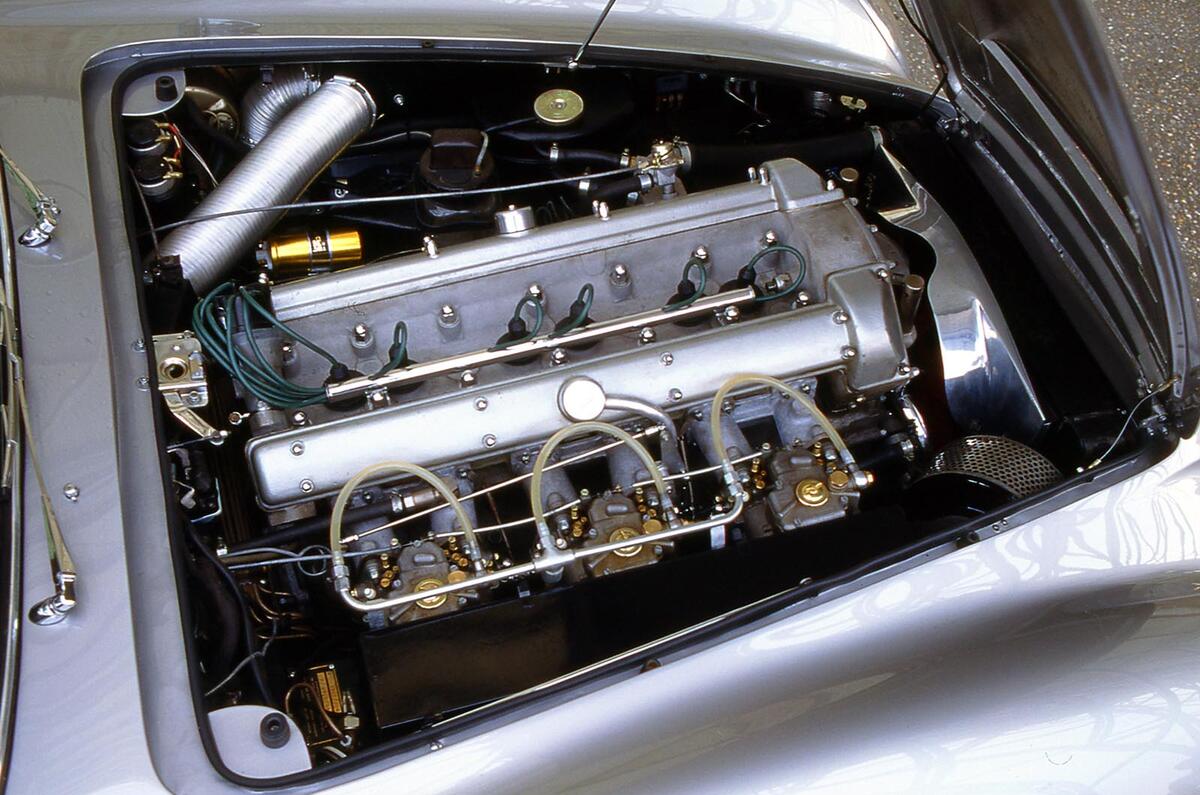

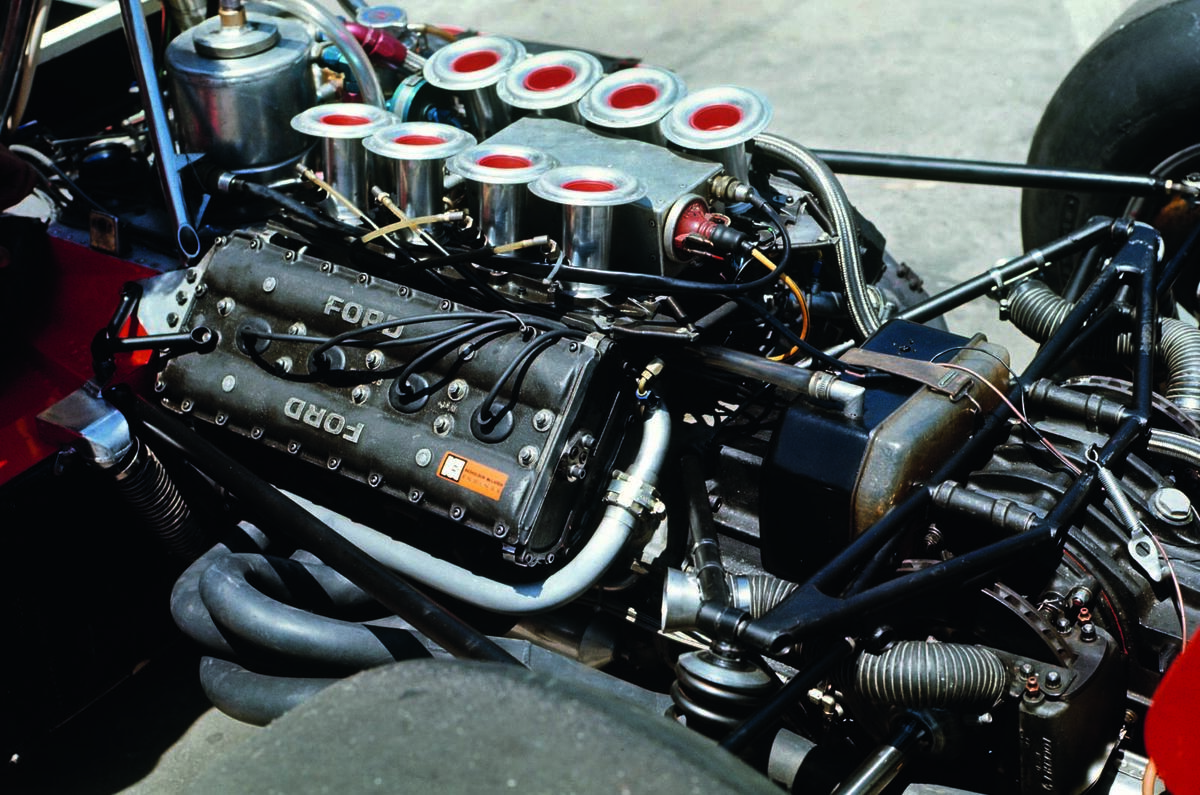

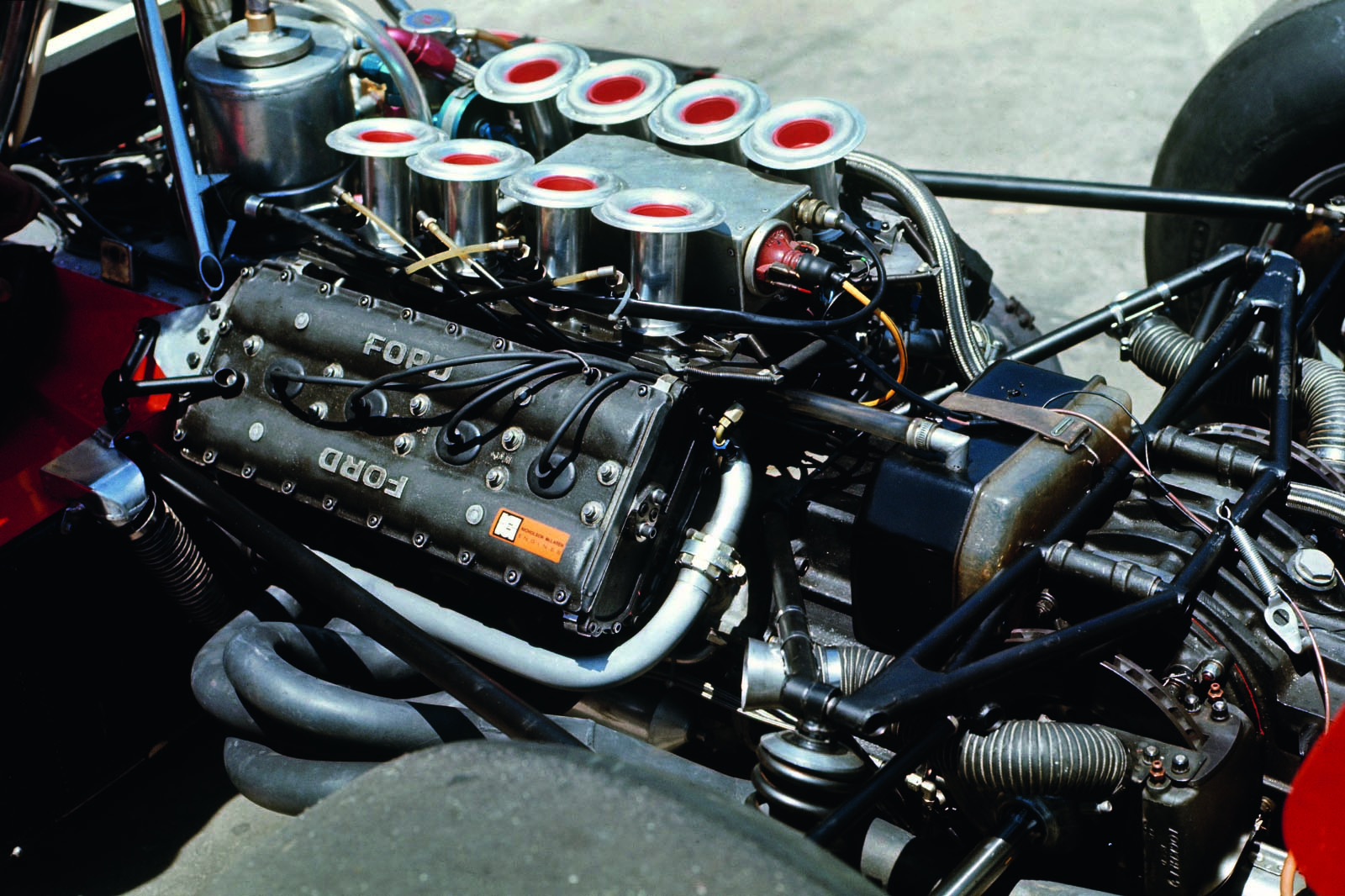

There is no better example than Aston Martin, which, in its entire post-war history, has designed from scratch just two of its own engines: the straight six used in the DB4, 5, 6 and S, and the V8 used in the DBS and all other Astons with the exception of the DB7 up until the turn of the century. Both were nightmares to develop. Everything else was designed elsewhere, from the motor Aston inherited when it bought Lagonda after the war and used in the DB2 (designed by none other than WO Bentley) to the V8 used in the current Aston Martin Vantage, which was originally sourced from Jaguar. Even the current V12 can trace its roots back to the union of two Ford V6 motors.

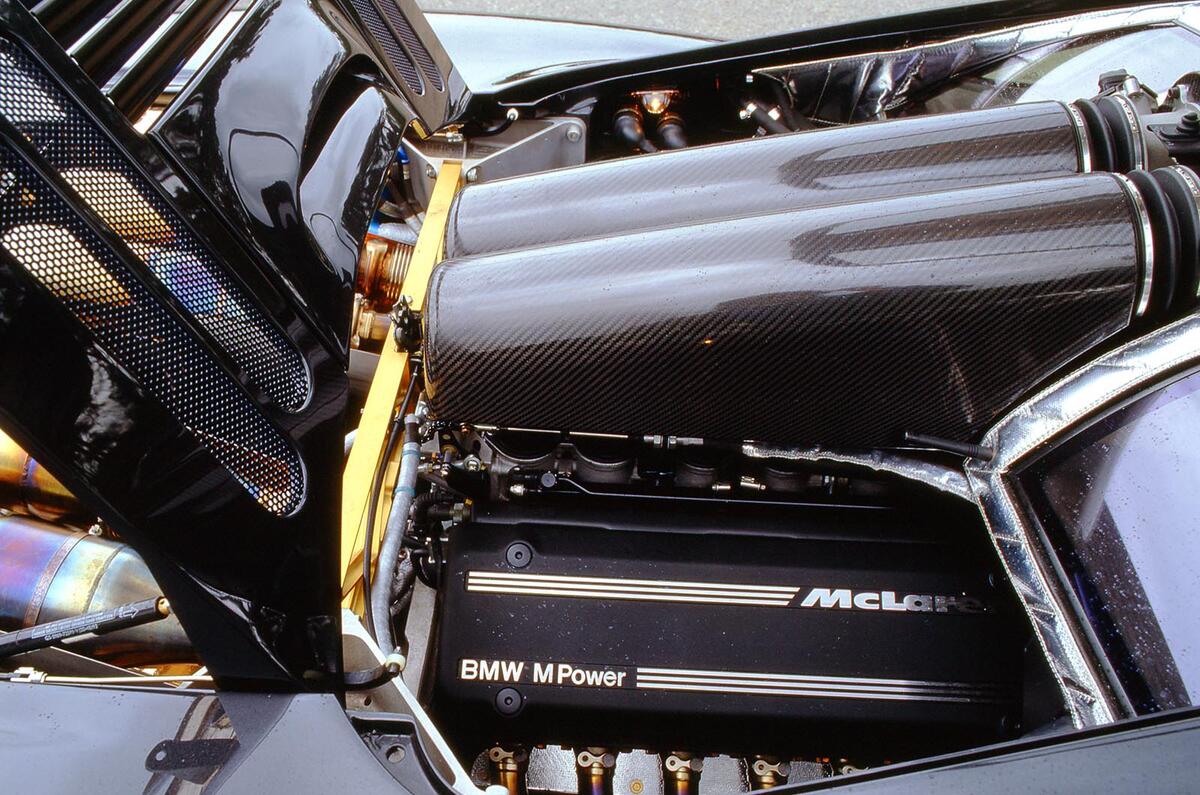

Some of the world’s greatest cars use other people’s engines (OPE). The McLaren F1 famously used a 6.1-litre engine sourced from BMW, and arguments rage to this day as to what engine or engines from BMW’s standard range it was based on. The engines in modern McLarens have evolved beyond recognition but are still ultimately derived from an IndyCar engine developed for Nissan by Tom Walkinshaw Racing but never used. Even the W16 engine used in the Bugatti Bugatti Chiron and Veyron can trace elements of their architecture back to the W8 engine that appeared briefly and somewhat implausibly under the bonnet of a Volkswagen Volkswagen Passat.

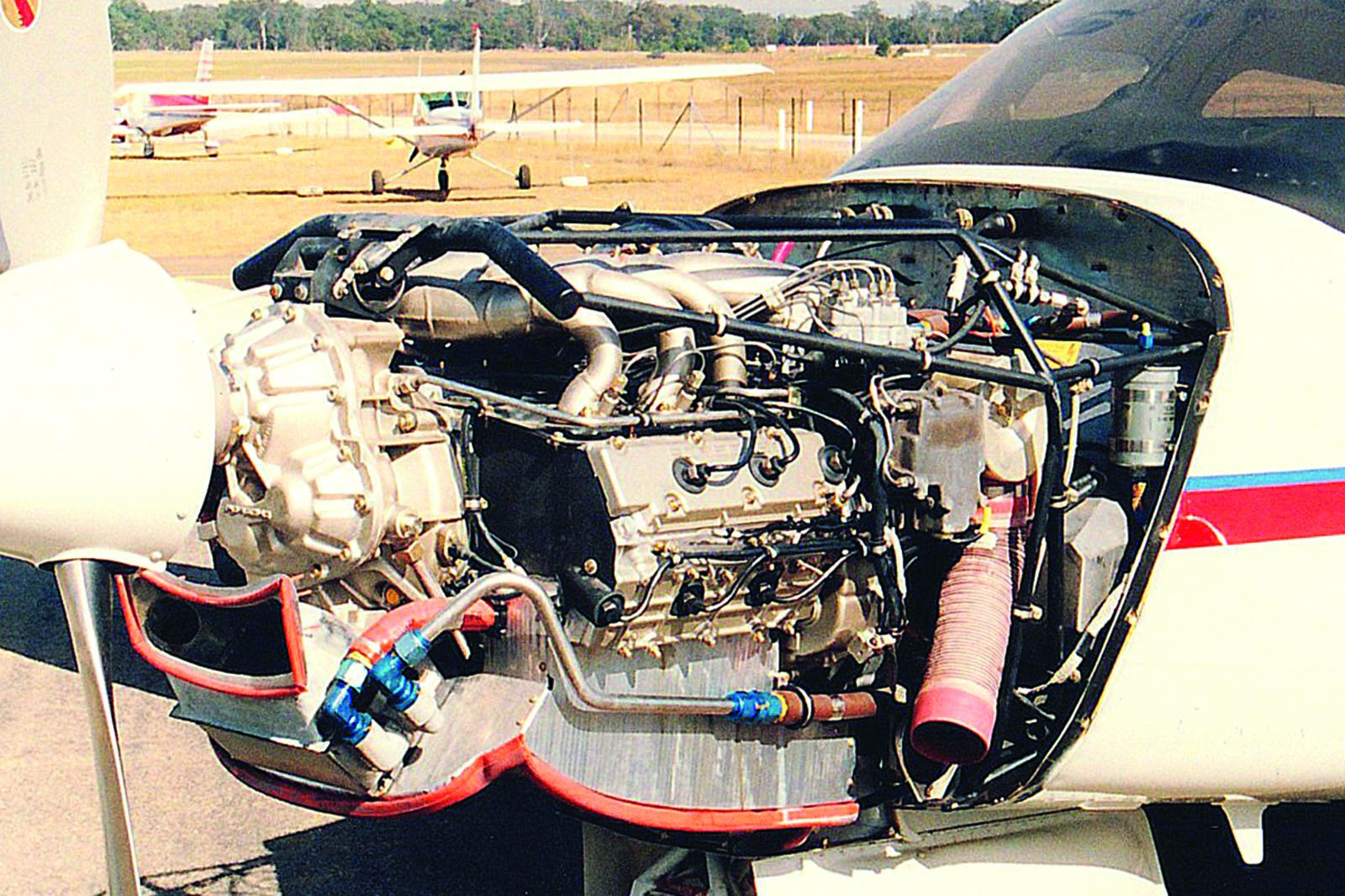

Aston Martin is not the only small manufacturer to abandon the idea of doing its own clean-sheet engine designs. Remember the Lotus Esprit V8, with its beautifully compact and pretty home-grown 3.5-litre twin-turbo engine? If ever there was an engine that was better on the drawing board than on the road, this was it.

It sounded terrible and had serious early reliability issues. Ever since, Lotus has sensibly relied on OPE.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Don't think anyone mentioned...

...Rover's V8. Designed for the Buick Special but dropped (too expensive to make?) Sold to Rover in the 60s, at first to power the ageing 3.5-Litre then also the 3500. Still going strong!

The Beast

I saw the car at a model aircraft display at Kempton Park in 1974, and I still remember how shoddy and rusty the engine bay was.

Whether you like it or not, it will become more frequent

I was informed recently that JLR & BMW will form a joint alliance to build new v8 engines, both diesel and petrol,as it is adeclining market,all engines getting smaller so the v8 is the old v12 and v6 the old v8 so to speak.Not even mentioning the e word.