It was a drive in the new 4.0-litre Porsche 718 Cayman GTS that did it. I took the car on the exact same route on which I’d recently driven the Cayman GT4 – just to see whether the normal GTS could get even to within viewing distance of standards set by its vaunted sibling and product of Porsche’s fabled Motorsport division.

But, as I drove, something appeared to be wrong. It wasn’t meant to be like this. I was actually having just as much fun in the GTS as I’d had in the GT4. You couldn’t use the GT4’s extra grip on the public road, but you could certainly appreciate the surer foot of the GTS’s less extreme tyres on the often wet surfaces, as well as the clearly superior ride quality.

Was the steering any less lucid? You’d need them side by side to tell. Was it significantly slower? Did it sound any less good? Was I, in short, enjoying myself any less as a result? Not that I could see. But the GTS costs £11,000 less than the GT4, so does that not make it therefore the better car?

It’s certainly possible, and I’d say definite for someone looking for such a device as a daily driver, rather than occasional recreation. Which started me thinking about other ranges where the headline grabber may not actually be the best of the bunch. What about those cars which are neither too hot nor too cold, but just right?

Defining the automotive Goldilocks principle

I am not the first to have thought about this. Indeed, it’s a well-documented concept with applications in medicine, economics and science called, predictably enough, the Goldilocks principle. By far the largest and most obvious example is our planet, as we’d all find out to our considerable cost were we ever rash enough to try to live on Venus or Mars.

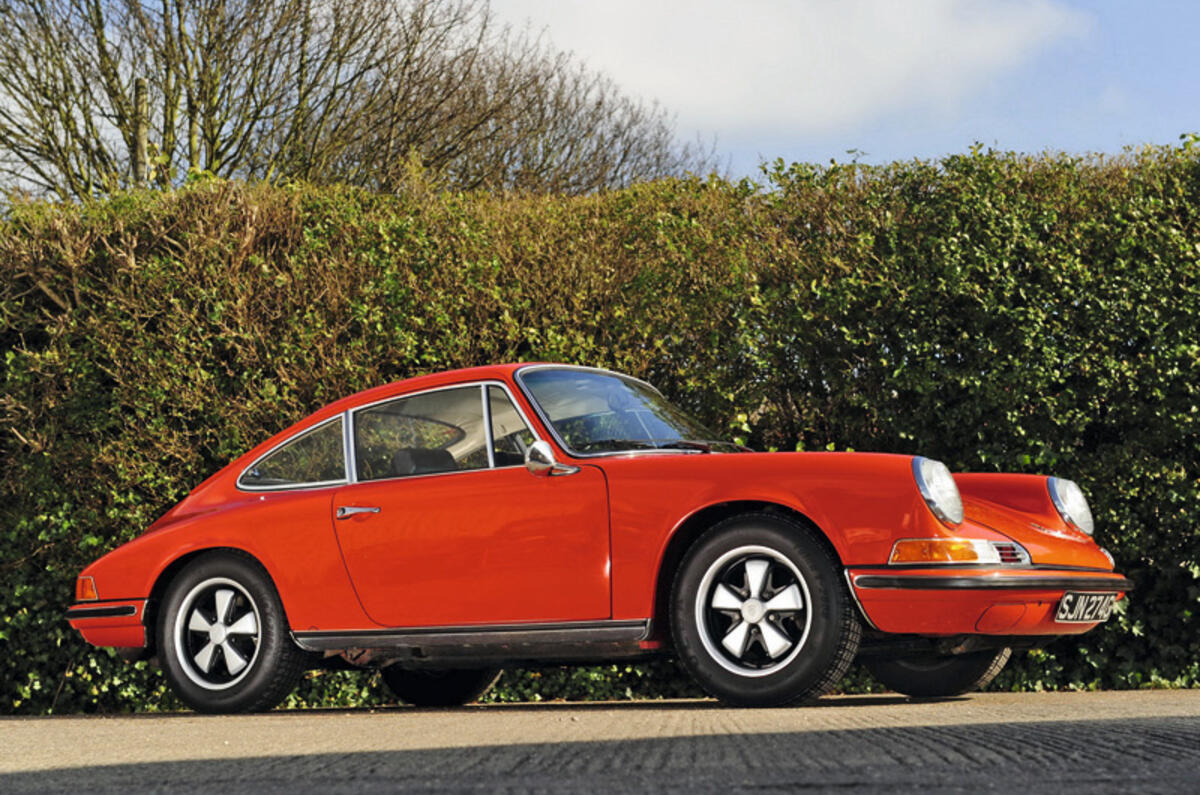

Goldilocks cars are nothing new. They’ve been around at least since the 1920s, when the six-cylinder Bentley Speed Six was at times compared unfavourably with the four-pot 41/2-litre model because, as someone put it, ‘I miss that bloody thump’. More recently, the 3.8-litre six-cylinder Jaguar E-Type was a far better driver’s car than the flabbier 5.3-litre V12 E-Type that followed it at a discreet distance.

An Aston Martin DB4 is a better driver’s car than a DB5, a Mk2 Volkswagen Golf GTI nicer than the same car with 16 valves. And an original S3 Lotus Esprit is a better car than an Esprit Turbo as well. Controversial, I know.

More recently, the shining example has to be the original Audi R8 with its super-sweet V8. The V10 that joined it sounded cool, but it spoilt the balance in terms of its handling neutrality and feel, and the balance between the powertrain and the chassis in determining your progress.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Great article. The obsession

Great article. The obsession with making cars faster and faster, with performance and grip completely unusable on public roads, at the expense of making the cars heavier or giving it a rock hard ride is a bad one...

this

is why i'm always wishing lotus would put a 100bhp honda S660 engine in a reintroduced Elise S1. It would be roughly as quick to around 100mph as the original, and lighter, with a lower percentage of the weight in the engine bay, and be an absolute masterclass in what a Lotus should feel like. Hopefully costing about the same as an mx5

Agree

I too very much subscribe to the less is more mantle. My first new car was the standard 8v Mk2 GTi and never had any aspiration for a 16v or the G60. Lower powered, lighter and more sensibly wheeled cars are generally sweeter to drive and more liveable everyday. I also had a Gen 2 997 911 and never regretted not buying the S which only had about 25 more horses. Spec exactly the same except for wheels (£1500 to upgrade) and exhaust. If I recall the price differential to the Carrera S was something like £8k which paid for the long list of pretty essential Porsche options including PDK and even Sat Nav. Same theory applies to current 992. Having owned three MINI Cooper S hatch's I would never considered a standard Cooper even though I did test drive the 3 pot when BMW closed the power gap between the standard Cooper and the S. Just no comparison - the Cooper is a perfectly nice Supermini runaround but the S is a proper hot hatch. I say proper because I think some of the fun is lost when the power output starts exceeding much more than 200 bhp. My current everyday car is a BMW i3s which is better than my previous standard car - not because it is that much more powerful but because of its lowered suspension, wider track and wider wheels that transforms it from a city car to a very warm hatch that with its low centre of gravity sticks to the road quite nicely.