Being rather brighter in outlook than my apparently sometimes-curmudgeonly demeanour might suggest, I spent lockdown trying if not exactly to see the sunny side of it then to at least learn any useful lessons that might be learned therefrom. And without sounding too profound, I’ve concluded that what matters most, other than the obvious, like family and friends, are experiences. All the things I recall with the most joy are those that I’ve done, not those that I’ve owned.

Yet you need at least some stuff in order to have those experiences. You’re not going to get very high up a mountain without some decent walking boots, nor jump out of an aircraft without, well, an aircraft out of which to jump. So I’ve been thinking about what you actually need in terms of equipment to experience driving in its purest, most easily enjoyed form. And the answer is right in front of you now.

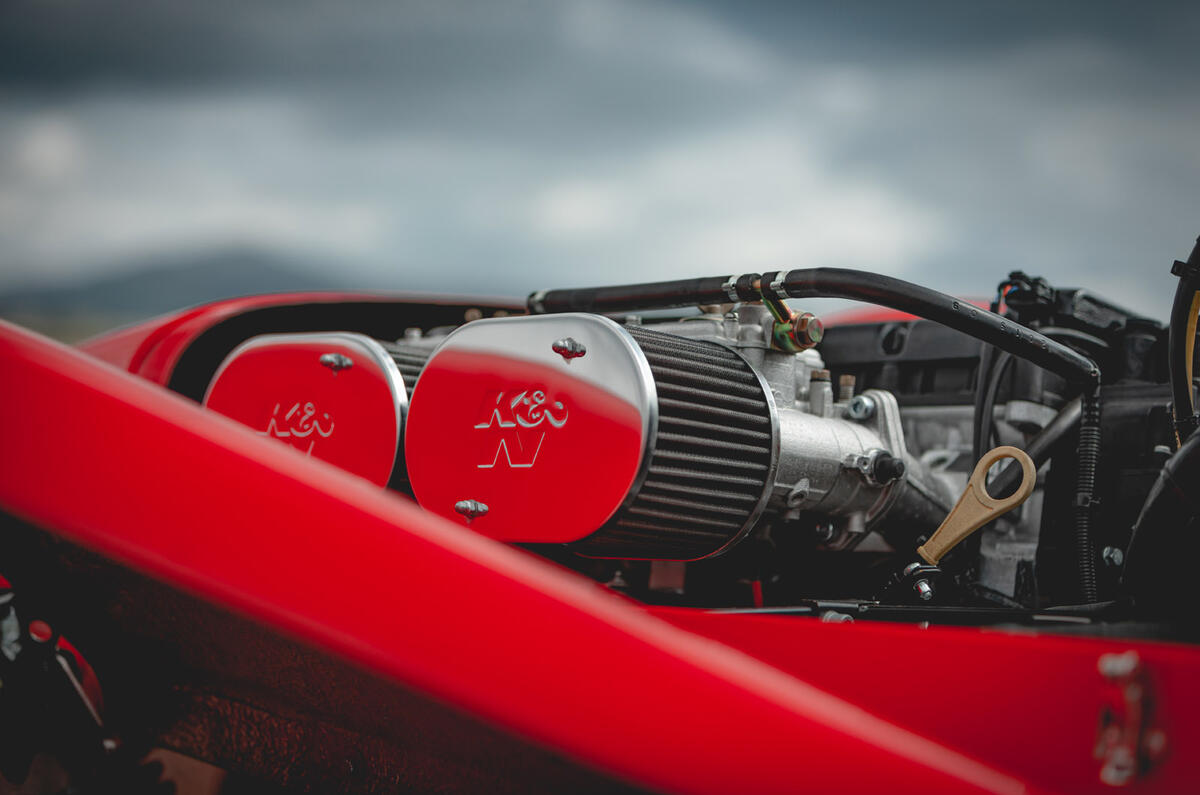

It’s a Caterham Super Seven 1600, the Super denoting its slightly olde-worlde style, with its flared wings, rear-mounted spare wheel and period-look Smiths instruments. But even if that’s not to your taste (as it is absolutely to mine), it doesn’t really matter; any simple Seven will do.

For this is not a whizz-bang supercharged brute that wants to pull you out of the back of the car every time you put your foot down, but a roadster powered by nothing more than a 1.6-litre motor, directing its modest 135bhp to the rear wheels via an open differential. It weighs just 1188 lb as standard, including its spare wheel and without having to resort to expensive options like carbonfibre seats.

If you’ve never driven a car that weighs so little, I can’t commend the experience more. We think of something like the Volkswagen Up GTI as being a tiny little flyweight, but actually it has almost exactly double the mass of this Caterham. And when a car also comes with a centre of gravity barely higher than the surface which you traverse, the result is a machine that drives utterly differently to any remotely conventional car. I’ll concede that being honed over a period of more than 60 years probably helps, too.

But it’s not quite absolutely back-to-basics and, for the experience we seek, that’s important as well. You can buy a Caterham without side screens, a windscreen or heater, and there are two consequences of doing so. The minor one is that you will save a tiny amount of weight; the rather more important consideration is that you will decimate the number of times you will feel inclined to use it. We took the pictures on this page up a Welsh mountain, and almost as soon as Max had pointed his camera at the car for the very last time, the clouds that had been gathering for a while suddenly started to unload on us. Within five minutes, there was a proper downpour – about which I cared not at all, because by then I was cocooned inside a completely weatherproof car, dry, warm, looking through an electrically heated windscreen and still enjoying the drive about a hundred times more than I might in any conventional car.

Add your comment