To recap, then, Volvo recently announced that it’s limiting all of its cars to 112mph from 2021. It followed that up shortly afterwards by saying it will also fit all new cars with technology to detect whether the driver is drunk or nodding off.

And now, all of a sudden, so is everyone else. As predicted, Volvo’s announcements stole a march on the EU’s declaration that intelligent speed assist (ISA, or speed limiters by another name) will be fitted to all new cars by 2022, along with drowsiness detection, ‘alcohol interlock facilitation’ and some other safety features. Volvo has been assserting that no one should be killed in one of its cars by 2020, but the industry and legislators as a whole have been quietly working towards a similar goal for some time.

Vision Zero is the name given to the loose collective of industry bodies, government departments and local initiatives that was started in Sweden in 1997 but which has since become a global affair. Its aim is simple and worthy if ambitious: to reduce road deaths to zero.

Trouble is, interested parties have been coming to the conclusion that in order to achieve that goal, some things are going to have to change quite radically. Cars are getting safer and safer, and if you’re inside a modern one, killing yourself is becoming really quite hard. The problem is those around them: pedestrians, cyclists and everyone not protected by two tonnes of impact-resistant metal box.

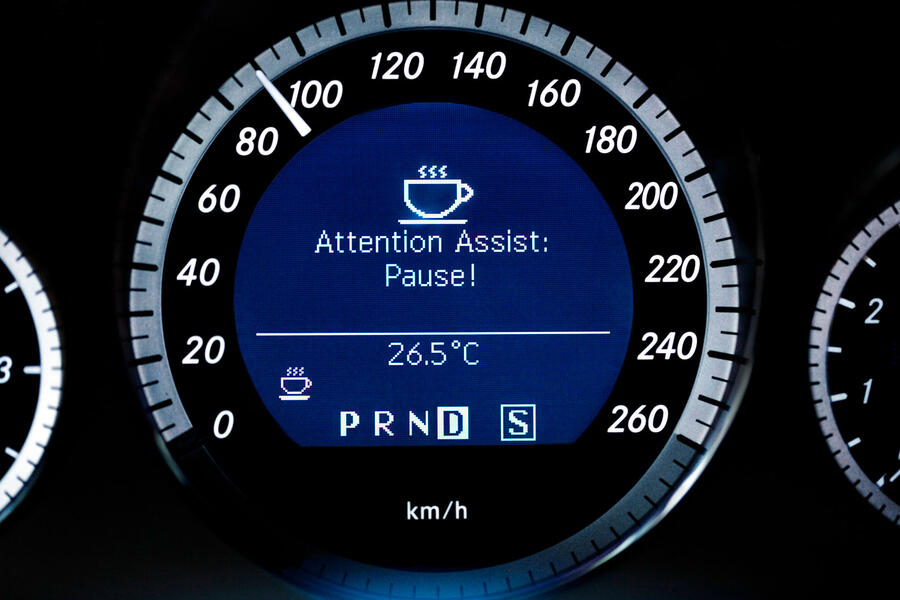

It’s telling that Volvo’s mandate is that no one should be killed ‘in’ one of its cars by 2020, not ‘by’ one of its cars. You might think that clever advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) would be the answer, but their development seems to have reached a bit of a bottleneck.

Have a read of the caveats and disclaimers in any number of current owner’s manuals describing how ADAS works, or doesn’t. Volvo says its City Safety system can detect cyclists, but only adult cyclists riding adult-size bicycles and not “partially obscured cyclists, or cyclists if the background contrast is poor, or cyclists wearing clothing that obscures the body outline, or bicycles loaded with large objects”.

Join the debate

Add your comment

No need to give up your license quite yet...

I think Peter C must have missed the data showing younger folk just aren't bothering to learn to drive and/or buy cars in the way previous generations did. Looks like it's self-regulating - driving was about freedom (and maybe fun!)...and if you're no longer free and it's not enjoyable, then why bother! The world is becoming ever more urbanised and for city-dwellers public transport just makes more sense. Which is surely good news for us oldies who continue to drive?

Have to start sometime....

Can’t just stand there and shake our collective Heads about this, yes, it seems an insurmountable problem, but, there’s going to be more and more traffic on the Roads, and I can see maybe mandatory surrender of licences at say 65-70 so as to free up space for new younger drivers, otherwise we will need good Train, Plane, Ship services. I don’t envy people who live in Cities or commute into them, must be very stressful, so to say limiters or autonomous speed control isn’t a start is a bit short sighted.

Found the ideal test area for automated vehicles!!

Having been in Rome recently, I'd like to put it forward as the ideal area for testing autmated vehicles.

An unnerving drive in a taxi, which was swapping lanes with inches from other cars to spare, exceding speed limits, giving pedestrians on a crossing a few inches of room, makes you wonder how an automated system, programmed with safety in mind, would ever cope with the kamikaze driving.

The automated car would also struggle with the way pedestrians dart into the road.

And that's without the motorcyclists weaving in and out of traffic....