Being all things to all people is something combustion engines have never been much good at but supercar maker Koenigsegg may at last have that one licked with its Freevalve technology.

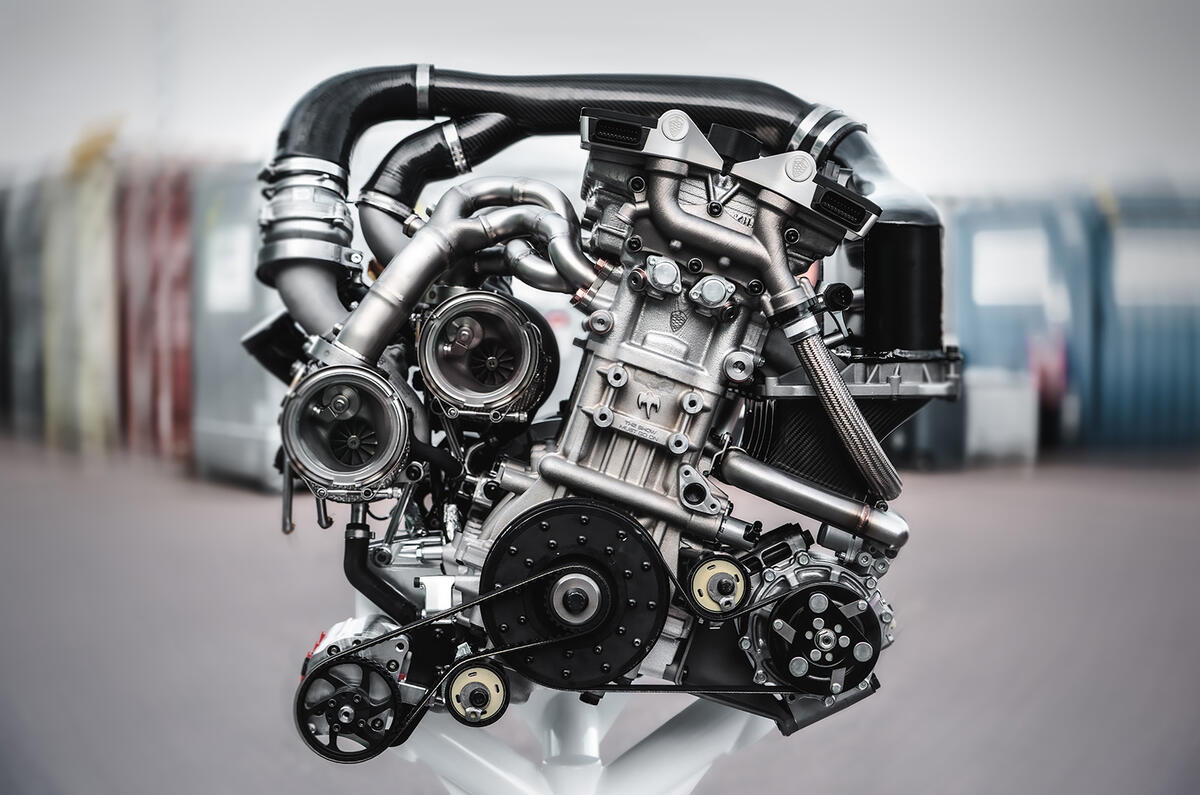

Freevalve does what the name neatly implies: frees inlet and exhaust valves from the constraints of the traditional camshaft used to open and close them. The technology was aired in the TFG (The Friendly Giant) engine of the Koenigsegg Gemera at the virtual Geneva motor show in March and is due for production in 2022.

The so-called ‘camless’ engine isn’t a new idea and many concepts have emerged from companies such as BMW, Renault, Fiat, Lotus Engineering and, more recently, British company Camcon. Fully individual control of valve timing and lift (when they open and close and by how much) potentially offers huge benefits such as reduced fuel consumption and emissions together with ultra-high performance.

The TFG engine can run unthrottled, so the amount of air entering the engine can be controlled internally by opening the valves less, rather than restricting it by an external throttle upstream of the engine. That saves energy. The engine can easily run in the efficient Miller cycle, where the volume of air ingested occupies a smaller volume than the expanding gases of the power stroke, increasing efficiency.

Most toxic emissions on a modern engine still occur inside half a minute from a cold start due to cold internals, cold catalysts and limited fuel-air mixing at low start-up rpm. The Freevalve system manipulates the valves to promote internal exhaust gas recirculation, thoroughly mixing hot combustion gases with fresh charge to reduce emissions by a claimed 60% when compared with a traditional three-cylinder engine with camshafts.

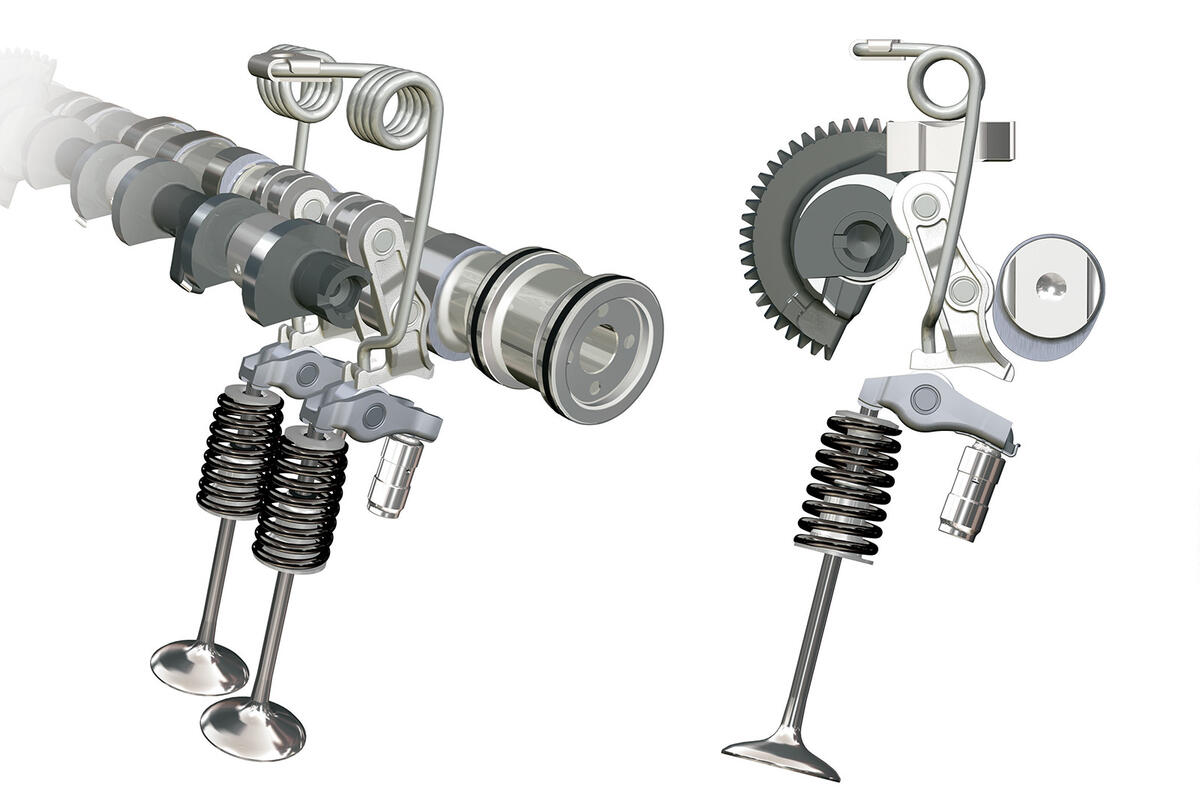

Earlier attempts at camless technologies were relatively simplistic, usually involving electro-magnetic solenoids, or electrohydraulic actuators. The Freevalve system uses pneumatics to actuate the valves and electro-hydraulics to stop the valve in a given position and dampen its movement.

It also enables cylinder deactivation by closing all the valves in individual cylinders and cutting the fuel injection. Plans include using artificial intelligence to let the engine figure out the best combustion strategy at a given moment.

The engine’s brain (electronic control unit) decides exactly what each valve is going to do depending on the load on the engine and what the driver is asking it to do via the accelerator pedal. The turbocharged engine has a two-stage turbo system, but instead of using valves to control which turbo actuates when, the Freevalve does that by connecting three of the engine’s six exhaust valves to the turbine of one, and three to another, controlling turbo boost of each independently.

The results look impressive. The TFG is a 2.0-litre three-cylinder engine producing 600bhp and 443lb ft, with fuel consumption claimed to be 15-20% less than a typical direct-injection 2.0-litre. It can run on a variety of fuels and is said to be CO2 neutral using second-gen renewable alcohol fuels.

Join the debate

Add your comment

CO2 neutral?

To believe that, the carbon dioxide absorption of the growing plants would have to equal the emissions of that gas when burnt. A bit of a coincidence, maybe, but I'm not disputing that. However it doesn't mean that engines burning such fuel don't have other harmful emissions that are either toxic or that affect the environment in other detrimental ways.

It's the combustion that has to stop, whether it be in engines, industry, cooking and heating or any other process. All unnecessary and harmful to our planet.

There is plenty of solar and wind/wave power, not to mention nuclear, capacity to provide for the world's population without the archaic, Stone Age solution of fires.

Robbo

A View from Down Under

Is it worth the effort?

There seems to be so much new R&D out there that is still being applied to the internal combustion engine and the fuels it could use - but to what end? Blinkered politicians, pandering to various hostile pressure groups and utterly unable, or determined not to, understand any of this new technology, have decreed that none of this should have a future.

I'd say yes. If it delivers

I'd say yes. If it delivers as promised, then 20 or so years with a better, cleaner engine is certainly worth it.

@Bob Cholmondley

The only diagram shown was of the Vanos system, which is fundamentally different to Freevalve and therefore served no purpose in illustrating the idea.