The mild epiphany came last year: I am probably the world’s worst small fleet manager. Apart from not quite knowing how many cars I had – 12, 13? – most of them had no MOT, no tax and few were runners.

This is the challenge of having a deep-seated urge to own a car museum, a busy job and limited mechanical skills. Having this many cars might suggest that I’m loaded, but no – most of them are cheap cars, bought cheaply.

One reason there are so many is a large one-time chicken shed. It’s eight miles from home and shared with an enthusiast mate and some other friends who store the odd car there. But it’s only the odd car. Most of them are mine. Once you have a space like this, the overriding temptation – for me, at least – is to fill it.

At its peak, mate Bryan and I have established that you can get 17 cars in if some are narrow enough to allow three abreast storage in this long, thinnish space. Having to park the cars in two nose-to-tail columns sometimes means quite a bit of shuffling, but this is far from the biggest impediment to enjoying them.

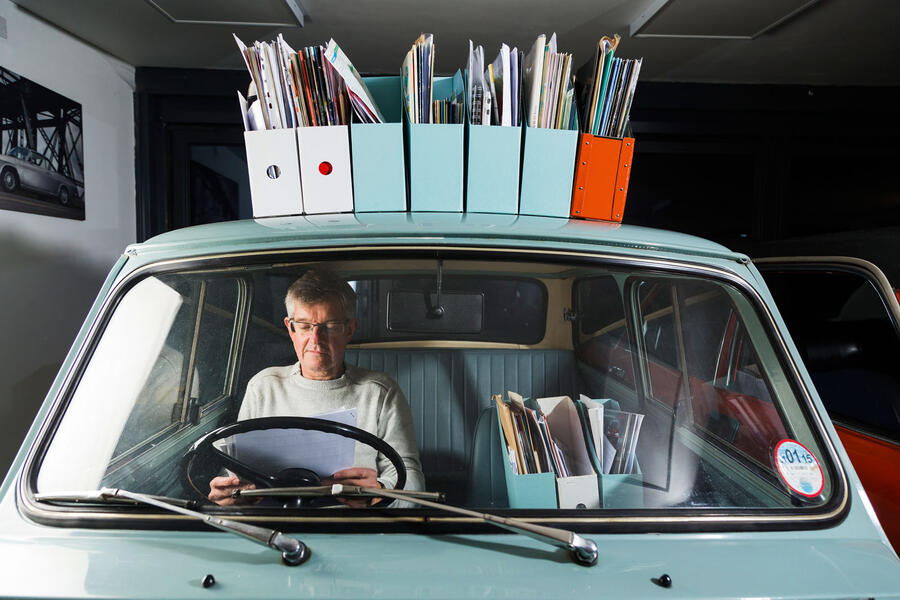

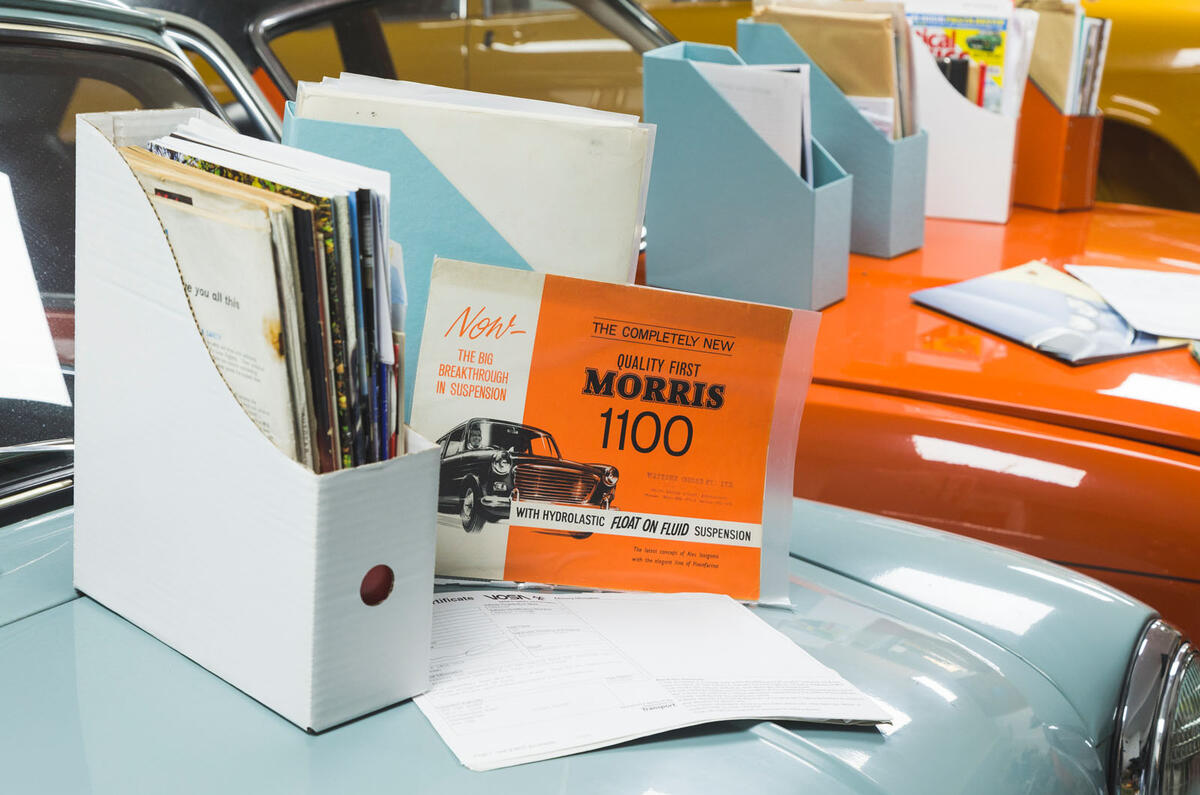

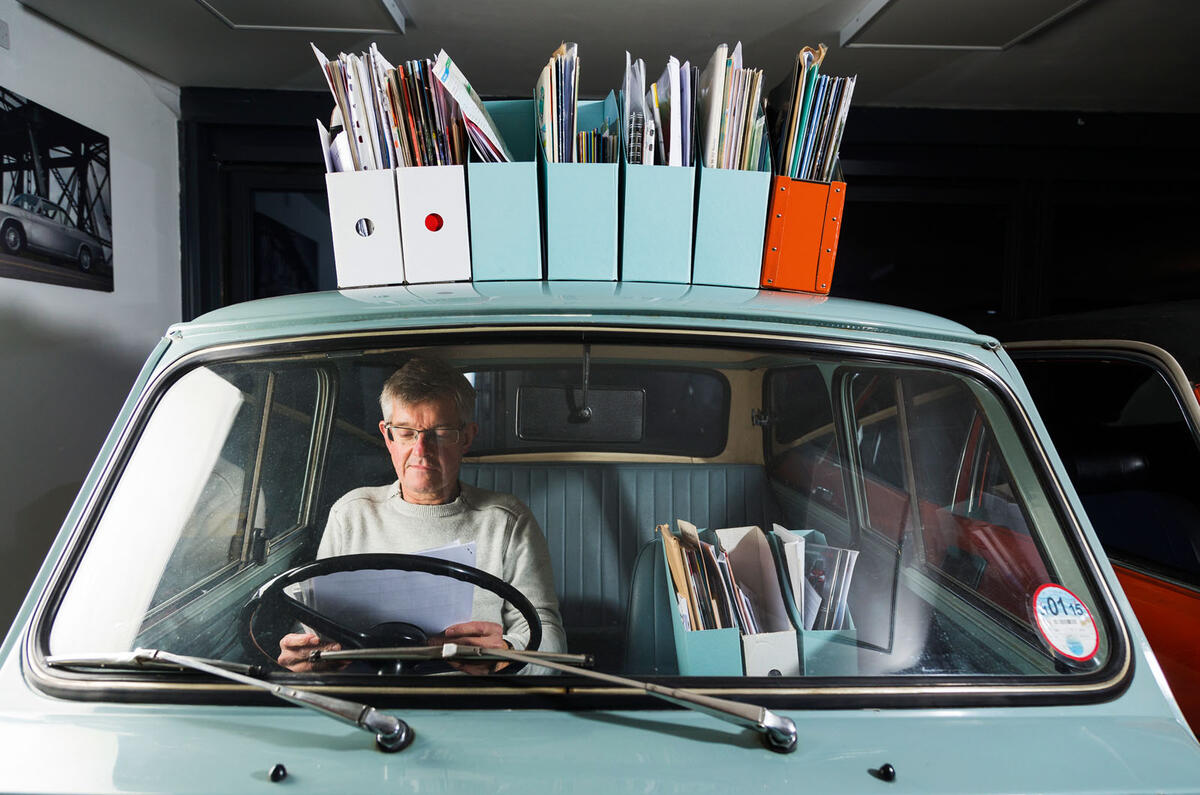

Instead, it’s me, and around 13 box files of documents, one for each car. They contain V5s, MOTs (mostly expired), repair bills, handbook packs and assorted historical paraphernalia, and if you’re to have a hope of keeping on top, you need to know not only the mechanical status of each car, but also whether it has MOT, tax and insurance.

Insuring them is easy. Most of them are on one classic policy renewed annually with Hagerty. That the policy is good value is another reason I have so many: it doesn’t cost much to add a car on, presumably because the insurer has worked out that you can only drive one at once, and because they won’t be getting used most of the time. Or any of the time.

Of course, I could use a spreadsheet. But that begins to turn the hobby into something like work and, when you look at it, rather rams home how much work there is to do. So I don’t have one. Instead, there’s a single A4 sheet with each car’s status on it. Sometimes, it gets updated. Mostly, though, I know which of my cars are road legal and, this year, following the epiphany, more are. Friends have sometimes helped – Bryan performed a full BMC-style service on my 1963 Austin Mini – and so has the nearby garage. Apart from the local used car dealer, I’m probably their most regular MOT customer. They let me descend into their pit to inspect the rust beneath each classic, which is useful, although it can lengthen the to-do list.

Join the debate

Add your comment

No Alfas?

I thought you were keen on Suds etcetera or is that another RB?

Collection of failures?

It's an interesting approach to have a collection of cars best known for their commercial or technical failure. The BMW Mini is an obvious exception and should be got rid of immediately!

Put 'em in a museum

Richard, I imagine you will know this but there is a fellow oop north, Richard Usher, who is creating an interactive museum for cars just like this. Called 'The Great British Car Journey' it is based in a large former mill near Matlock in Derbyshire. Usher also owns the Blyton Park circuit near Gainsbrough. Why not lend your cars to him and let him do the paperwork?