If you thought of MIRA pretty much as a test track in the Midlands, you wouldn’t be alone. When it was taken over by Japanese firm Horiba in 2015, The Telegraph’s first paragraph called the Nuneaton company a “car test track and development centre that has served as a playground for motoring shows like Top Gear and Fifth Gear”.

The set of tracks it was known for were laid over the former RAF Lindley’s runways and taxiways when that was re-purposed to become the government-backed Motor Industry Research Association’s base in 1948. When the chairman of Austin came to open the site officially, he brought a pair of ceremonial scissors, not knowing the MD had arranged to blow the tape apart with explosives.

Back then MIRA was a few runways and taxiways, a control tower and one hangar. When I started coming here about 12 years ago, because it’s where Autocar frequently conducts its performance tests, the tower’s first floor was still where you signed on to use the tracks. And I’m pretty sure the glass lookout on top was being used by a staffer as a greenhouse.

It wasn’t that MIRA, including the 1950s-built laboratories and offices at the front of the site, didn’t have enough work. It had so much it was at capacity. But the place needed to spend hundreds of millions of pounds it didn’t have on infrastructure.

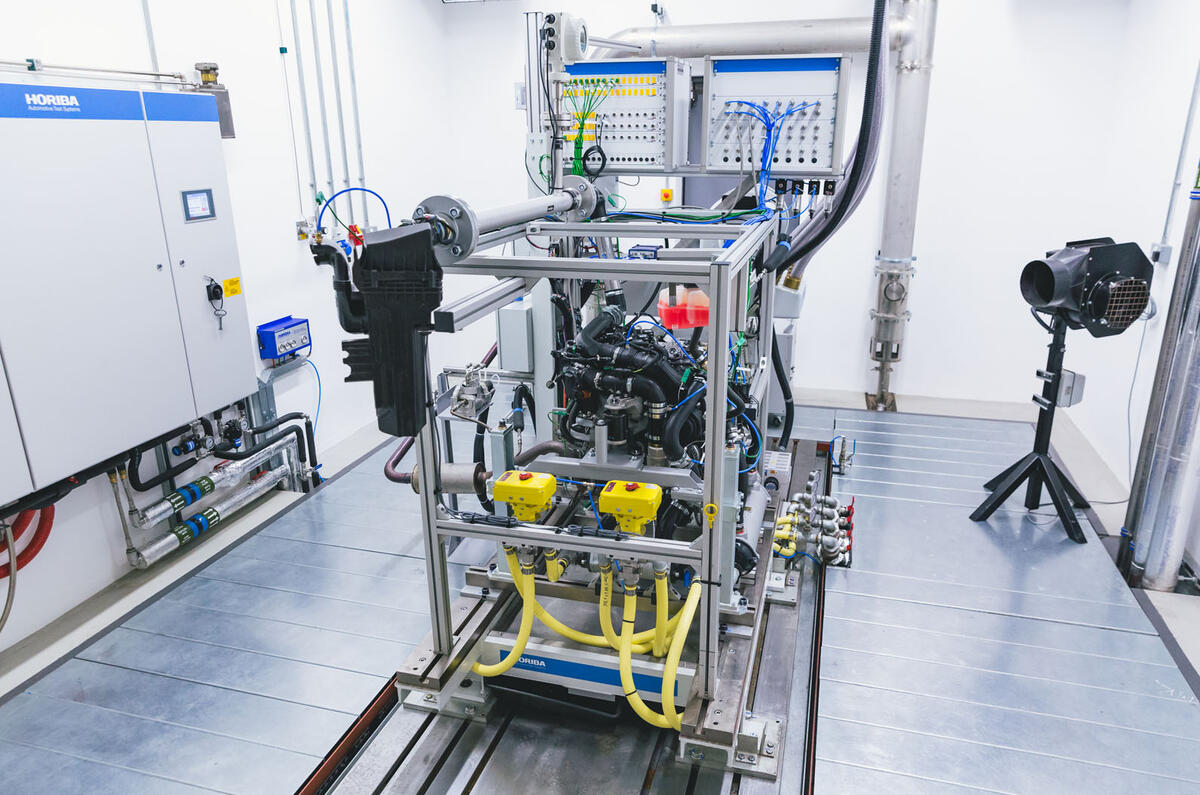

Some came – the control tower moved to a new building, at least – but it needed more, which is why MIRA began pitching itself to investors at the start of the decade and eventually found the right buyer in the Japanese company Horiba, who paid £85 million for it in 2015.

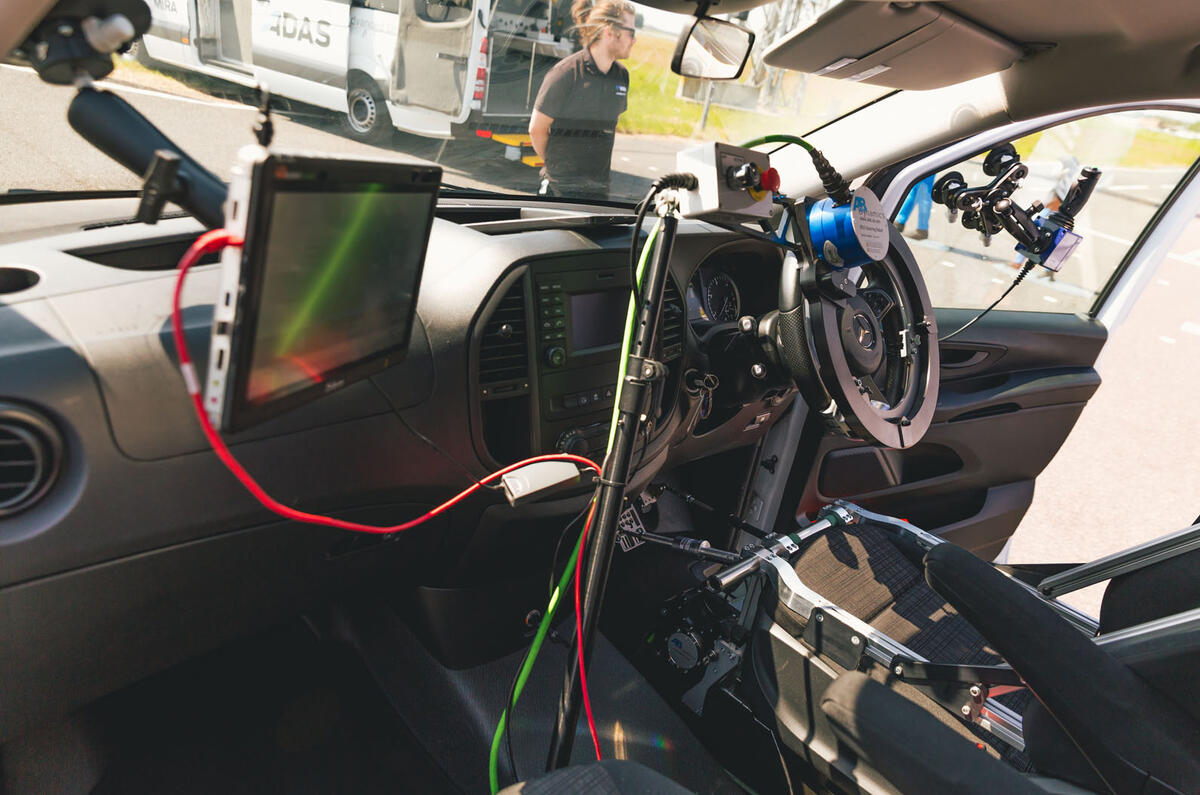

As an outsider – sometimes as a staffer – there’s an unknown about takeovers: are they asset-stripping? Will jobs go? Not in this case. Not a bit of it. The investment since has been staggering.

Add your comment