It turns out there’s an 11-week lead on a half-hour audience with Philippe Krief. Surprised? Don’t be. In September last year, the man from Marseille became the Renault Group’s new chief technology officer.

This would be a substantial professional endeavour even if the 60-year-old hadn’t, only the summer before, also left Ferrari and taken on the role of Alpine CEO.

Somehow he does the two jobs side by side, each day scoped to the minute. It’s hardcore.

Mr R&D for vast Dacia, even more vast Renault and ‘vehicle as a service’ provider Mobilize is also on the hook for the resurgence of a brand some believe can, in the EV era, wield a degree of clout similar to that which Porsche amassed in the petrol age. So Krief is busy – but if you manage to pin him down, he makes for fascinating, steely company.

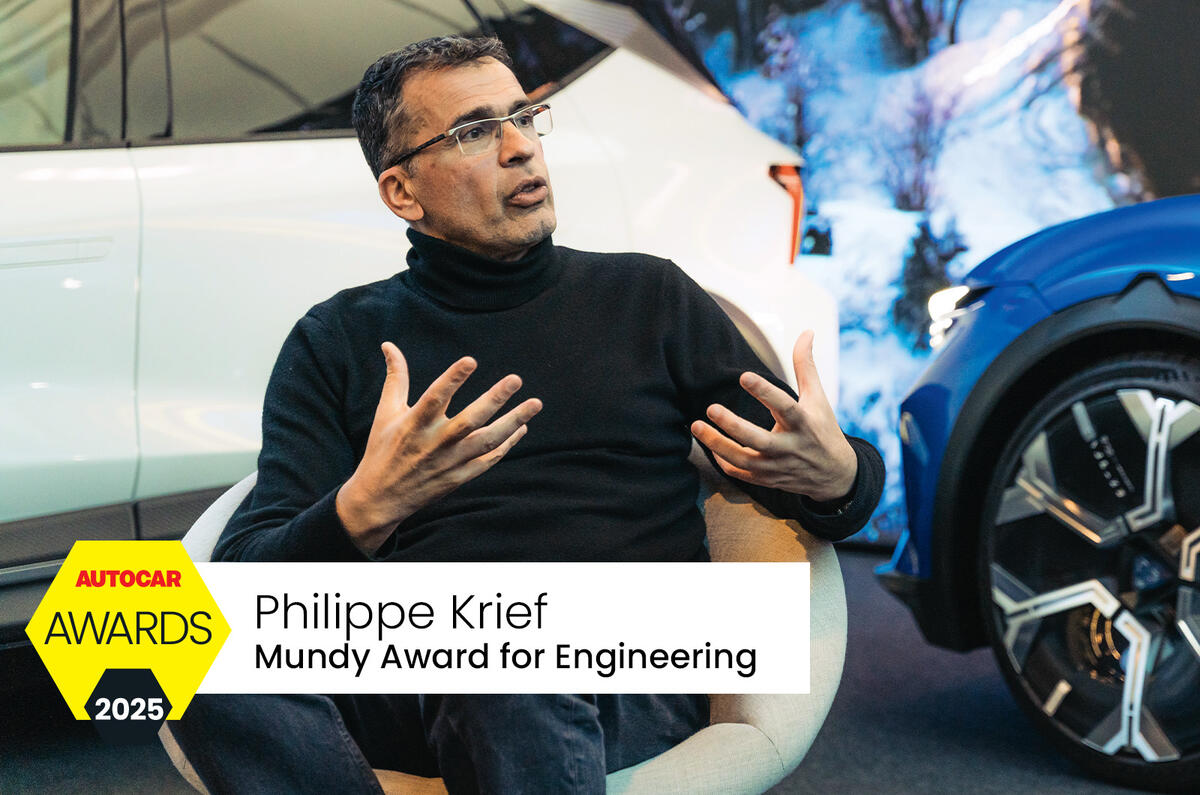

It was obvious from the nervous energy of the comms staffers, with whom we were awaiting their CTO’s arrival in a grand exhibition space (replete with giant turntables) in the bowels of Renault’s Technocentre, that he comes with an aura. Not the full Tobias Moers – people weren’t profoundly intimidated, as was often the case when the ex-Aston Martin CEO was inbound – but a deep seriousness.

Brows were furrowed, chatter was clipped, chairs were arranged and rearranged. Then he was among us, in a black turtleneck more car designer than camber-geometry tragic, five minutes early.

So who is Philippe Krief, winner of this year’s Mundy Award for Engineering? A born engineer, for one thing. With high-flying execs the car bug is so often inherited, but neither of his folks worked in the industry, instead running a removals business.

A successful one, admittedly – young Krief was rolling around in the back of DS Citroëns and had a soft spot for his father’s Peugeot 504 coupé (the Pininfarina one, he reminds me), so delectable metal was on the scene. But it wasn’t the impetus.

Engineering was the job he always wanted to do, “so I combined cars with my passion”, he says. Engineering was the desire, cars the vessel. The balance has since shifted, and Krief today can’t imagine engineering anything else.

He says: “The thing I learned, and that I now know would be difficult not to have, is the soul you give to a car,” he says. “You can feel it when you test drive it.” I guess you can’t get quite the same kick from designing an MRI machine, or even an unmanned rocket.

Add your comment