Composite car components that use graphene are expected to make it to market in seven to eight years and could lead to the development of much lighter, more energy-efficient cars.

That’s the expectation of the University of Sunderland, which is spearheading a consortium promoting the revolutionary material. It is currently running a pilot plant in Japan.

Scientists at the university have been working on graphene — which, when added to carbon-reinforced plastic in a certain way, means a bumper made using the material is capable of absorbing 40% more energy than the standard item. This could lead to the creation of significantly lighter, safer cars.

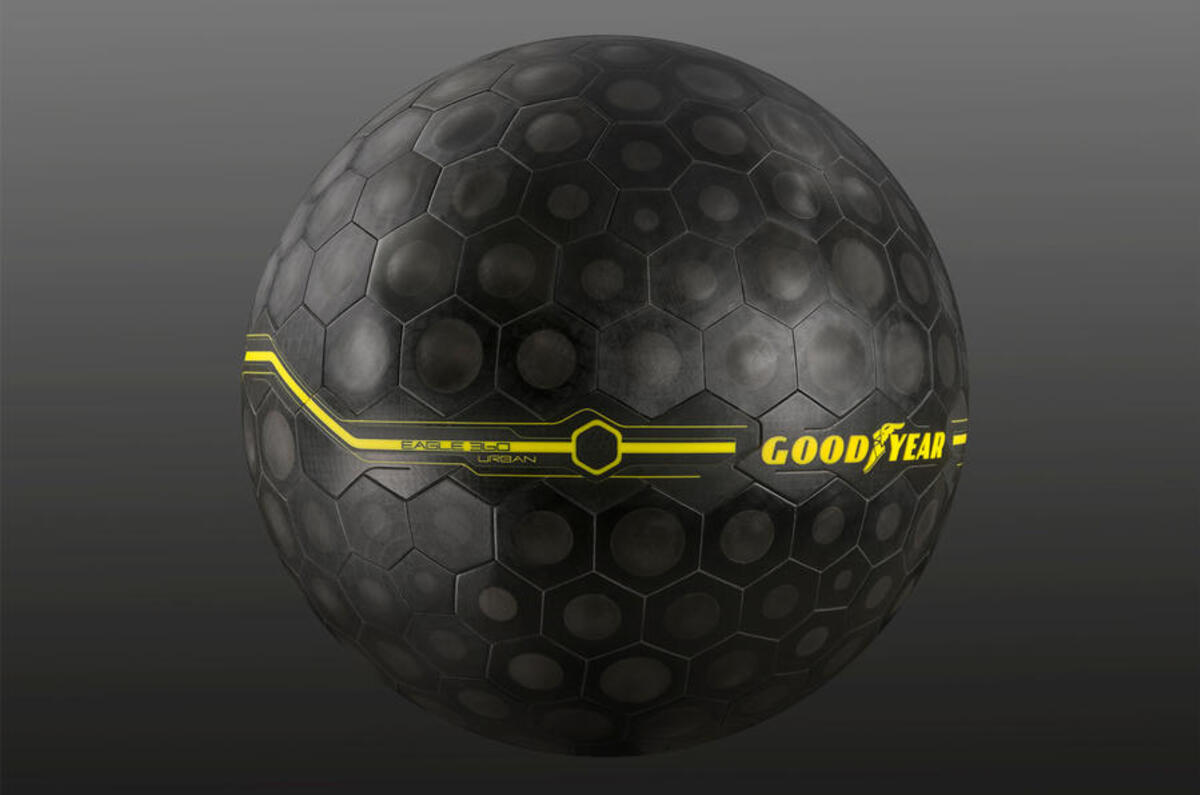

A number of organisations have recognised the potential of graphene in recent years. Goodyear talked about using it to create tiny sensors in the tread of its Eagle 360 spherical tyre concept, shown in 2016. The Advanced Propulsion Centre in Warwick recently held a seminar that brought together experts to discuss the potential of graphene, which was first isolated at the University of Manchester in 2004.

However, the University of Sunderland claims to be the first to physically test the technology, rather than simply theoretically table it, and has gone so far as to begin patent applications for certain parts of the process.

New ultra-capacitor tech could drastically boost battery EV range

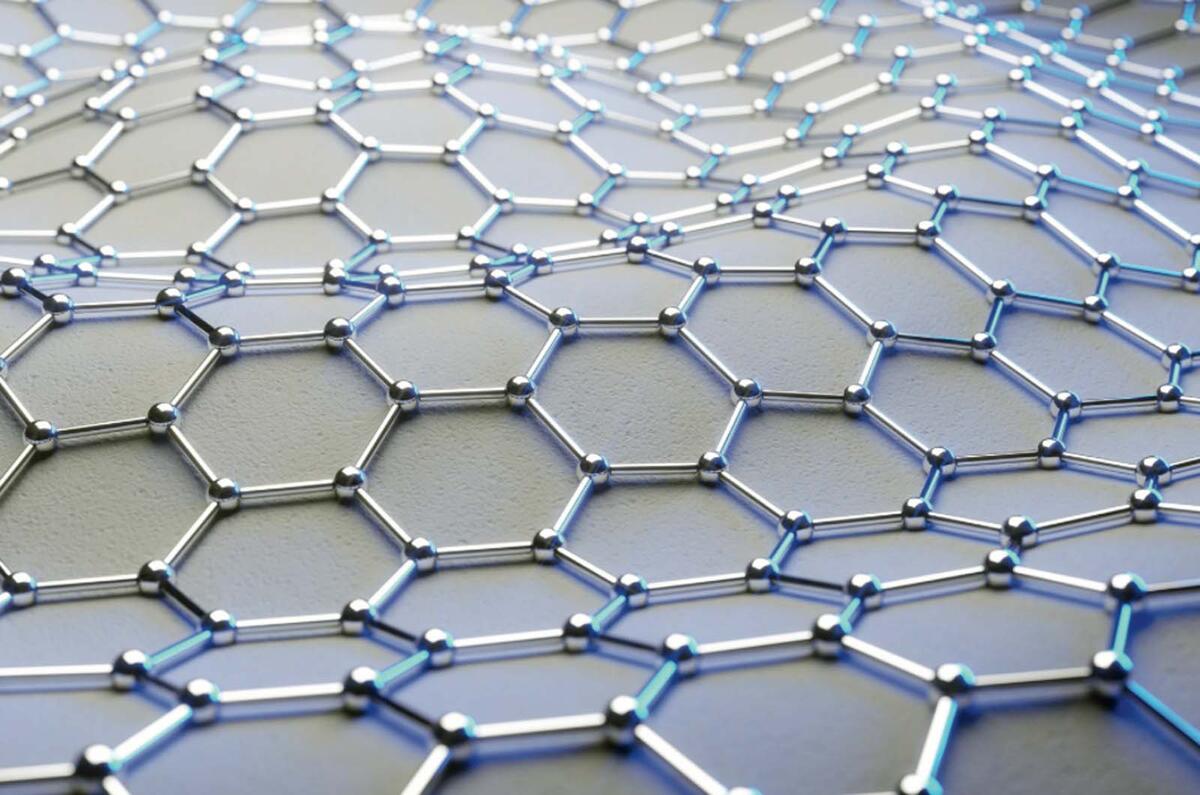

Graphene is produced by breaking down graphite, the same material used in pencils, to produce a material one-atom thick, or one million times thinner than a human hair. When turned into a powder, small amounts can be blended with the thermoset resin used to impregnate carbonfibre while it is still in liquid form.

The same technique can be used with thermoplastic material, which can be moulded when hot and becomes hard when cooled. In that case, the graphene is mixed with the plastic when it is melted.

When used in any kind of a crash structure or bumper, carbonfibre absorbs energy as it fragments. The addition of graphene in the right quantity improves this characteristic and gives the material other properties, too.

“The combination of materials creates a kind of toughness that absorbs some load, so it’s somewhere between carbonfibre and metal,” said Ahmed Elmarakbi, professor of automotive composites at the University of Sunderland (pictured above). The process can be used with glass-reinforced plastic (glassfibre) as well.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Future

Although the overall weight of new cars has increased markedly in the last 40 years, and it's a good target for the manufacturers keen to lower said weight. The reality is that in 40 years time, all new vehiles will be full electric. So the real breakthrough here is buried down in the second to last paragraph. A Tesla model S with a 100KWh graphene battery pack would weigh almost 300kg less than the current lithium unit (and still supply the same range). If you want to save weight, look no further...............

Sounds promising

Creation of a hybrid polymer could be a good route, blending the properies of both materials in smaller quantities, so this sounds promising.

I'd like to know