It was quite a big weekend for motorsport. There was a Formula 1 race in Azerbaijan, which is in Europe, apparently, and of course there was the Le Mans 24 Hours, in France, which is definitely in Europe. Meanwhile, the BTCC circus pitched up at Croft, in North Yorkshire, which remains in Europe at least for the time being.

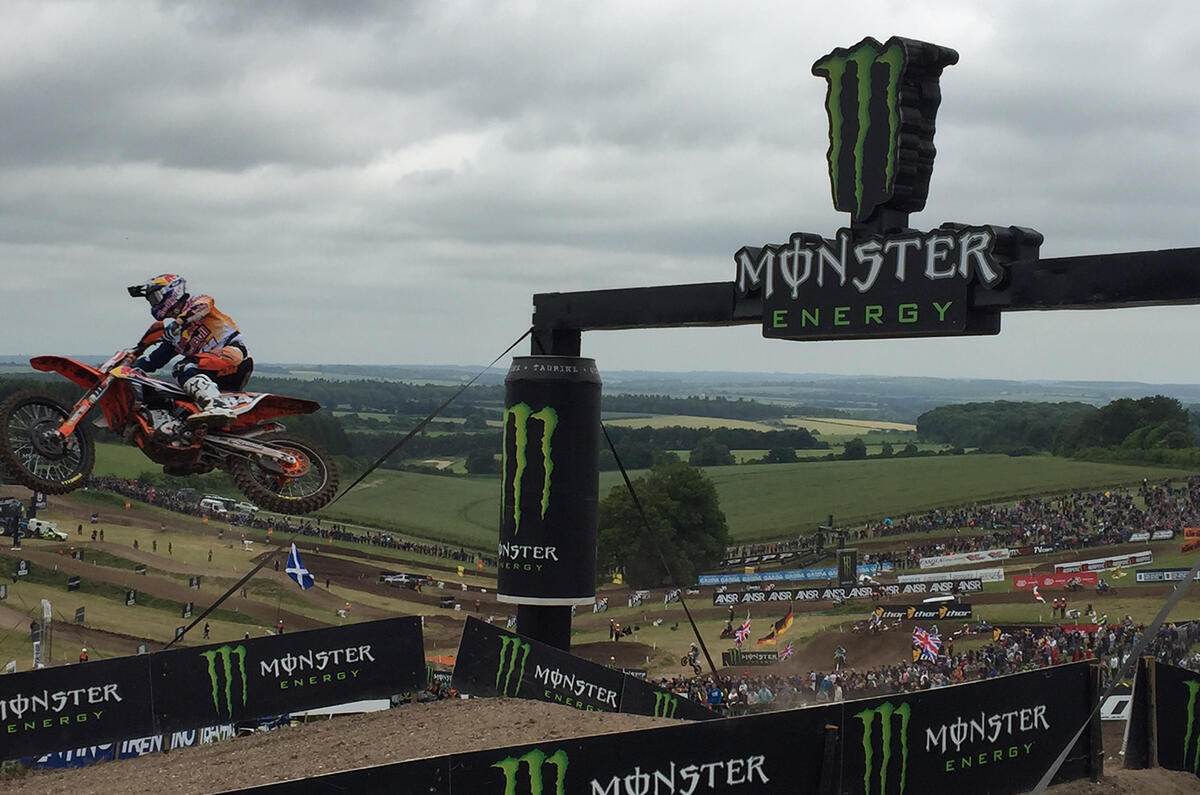

There was action on two wheels, too. The Misano circuit in Italy hosted the San Marino round of the World Superbike Championship, while back on home soil there was another world championship event – the British round of the World Motocross Championship, held at the pleasantly picturesque Matterley Basin in Hampshire.

It was this to which Autocar editor Matt Burt and I paid a visit on Sunday, courtesy of the nice people at Dunlop, who are currently in the process of helping us out with a very exciting feature coming this way soon. So watch out for that.

Anyway, the riders and drivers competing in the above events – or in any top-level motorsport – are what you might refer to as ‘quick’. They are really, really good at driving, or riding, fast. That’s a given. The thing is, there’s very often quite a bit more to it than simply steering, braking and accelerating, albeit in exactly the right way and at exactly the right time.

The stuff that you (possibly/probably) or I (definitely) would have to concentrate on 110% in order to set a personal best lap time around, say, Brands Hatch, happens on autopilot for real, actual racers. It’s the other stuff that makes the difference.

Talking to Steve Cropley before the Le Mans race, Ford drivers Marino Franchitti and Harry Tincknell both spoke of the apparent ‘serenity’ of driving down the Mulsanne Straight at 200mph in the dark.

Take Formula 1. Last year we published an interview with the British racing driver Gary Paffett, currently a DTM driver in Germany’s and test driver for the Williams F1 team. Last year he was McLaren’s test driver, and what he had to say about driving various McLaren F1 cars over the years was, frankly, astonishing. If you haven’t already read it, you really should.

It’s a fascinating and quite brilliant insight. We’re almost too familiar with F1; watch it on TV or even trackside and it’s easy to take what the drivers are doing for granted, but Paffett’s wide-eyed, fanboy-like description of what’s going on in the cockpit of an F1 car is truly enlightening. It should be essential reading for any jaded motorsport fan.

It’s not just on four wheels that the competitors go above and beyond. In motorcycle racing, riders drag along the ground bits of their bodies that most of us would be happy to keep well away from the surface of a race track.

But saving slides, and therefore crashes, on the knee – or even elbow for crying out loud – is par for the course in bike racing. Or, if you’re Marc Marquez, why not make use of pretty much everything from your ankle to your head?

Add your comment