Some utterly brilliant engineering has gone into the grim task of creating bombers in Britain.

While many formidable British bombers did go into service, such as the Lancaster, Canberra and Victor, many promising designs fell by the wayside. These cancelled projects offer a tantalising glimpse into what could have been. This is such a fascinating subject, we could happily do another 10, and maybe we should soon. Here are 10 Cancelled British Bombers.

10: Short Sperrin

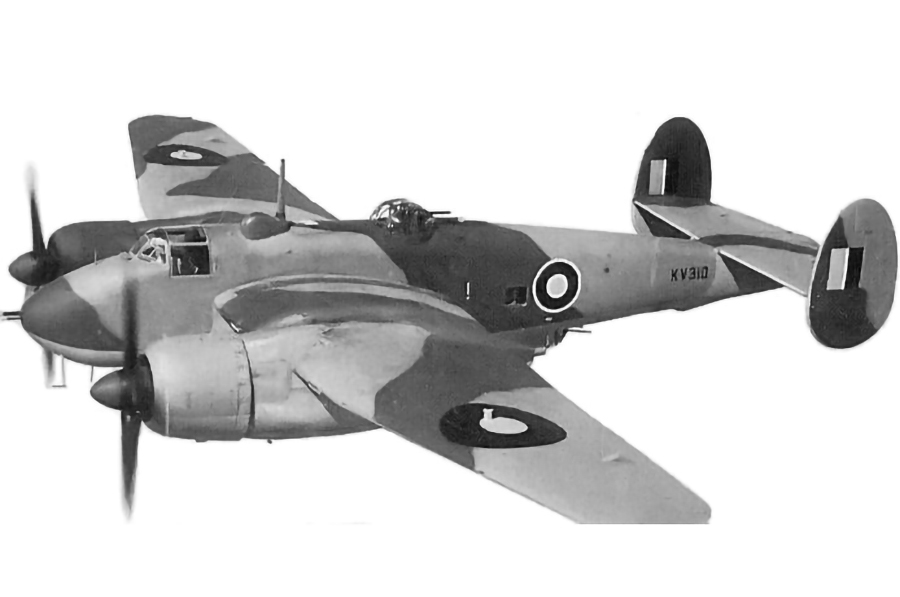

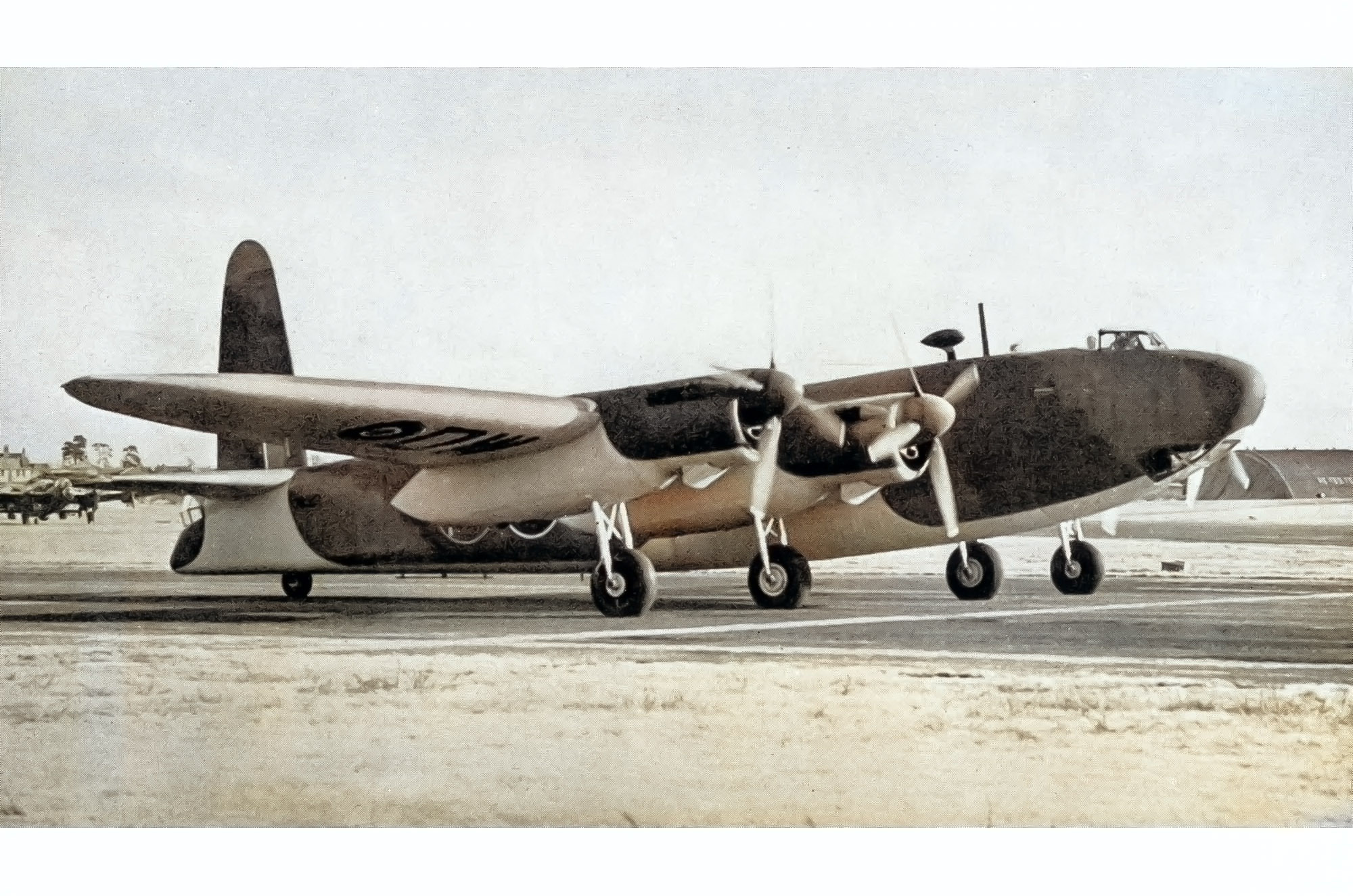

The Short Sperrin was a British experimental jet bomber developed in the late 1940s to early 1950s by Short Brothers. Conceived as an insurance policy during the development of the V-bomber force (Vulcan, Victor, and Valiant), the Sperrin was intended as a low-risk, relatively conventional alternative.

In the uncertain post-war technological climate, the British Air Ministry issued Specification B.35/46 calling for an interim bomber that could be more quickly and easily produced using proven technologies, in case the advanced V-bomber designs failed to deliver. The Sperrin’s most distinctive feature was its unusual engine configuration.

10: Short Sperrin

Unlike most bombers of the era, it was planned to be powered by four turbojets, mounted in paired nacelles under each wing — two engines per nacelle. This layout was not only aerodynamically unconventional but also increased drag, a compromise accepted for simplicity and redundancy. The aircraft’s conservative airframe design also contrasted sharply with the radical, crescent swept-wing or delta concepts of the Victor and Vulcan V-bombers.

Only two Sperrins were built, serving as testbeds rather than operational aircraft. Though it never entered service, the Sperrin played a vital role in validating systems and technologies, ensuring Britain had a fallback option. Its legacy lies more in its developmental support role than in front-line service, reflecting Cold War-era strategic caution.

9: BAE Systems Nimrod MRA4

As the Nimrod MRA4 had a very serious attack role, we will count it as a bomber. The Nimrod MRA4 was the UK’s ambitious but doomed attempt to replace its ageing maritime patrol aircraft, the Nimrod MR2. It promised cutting-edge technology, improved endurance, and new mission capabilities. It was plagued by delays, cost overruns, and technical challenges from the start.

Despite integrating advanced systems, such as a glass cockpit, new sensors, and powerful BR710 engines, the MRA4 remained tethered to a 1950s de Havilland Comet airframe. The digital upgrades were impressive—but ageing hardware, shifting requirements, and a sluggish development pace meant it lagged behind modern alternatives. The RAF never received a single operational aircraft.

9: BAE Systems Nimrod MRA4

By 2010, after 14 years and around £4 billion spent, the programme was scrapped. The US-built P-8 Poseidon achieved what the MRA4 couldn’t: operational service and was much closer to being on time and on budget. While some MRA4 innovations influenced future platforms, the aircraft itself never flew an operational mission.

The cancellation left RAF crews disillusioned and the Kinloss airbase in Scotland gutted. Though many personnel rebounded into new roles, the episode became a textbook example of procurement failure. A blend of ambition, legacy constraints, and mismanagement, Nimrod MRA4 stands as a very expensive lesson in how not to develop a military aircraft.

Add your comment