Rule Britannia? Not always.

Considering they invented the aircraft carrier, Britain’s Royal Navy has really pulled out the stops ever since to field as many aircraft as possible that were too slow, too dangerous, too late, too expensive or sometimes all four.

Not content with producing their own obsolescent death traps, the Senior Service also took on cast-offs from the RAF and bought in the occasional American dud to swell the numbers of inadequate aircraft crowding the decks of their too-small carriers. Narrowing down this underwhelming armada to a flotilla of merely ten was a daunting and difficult task.

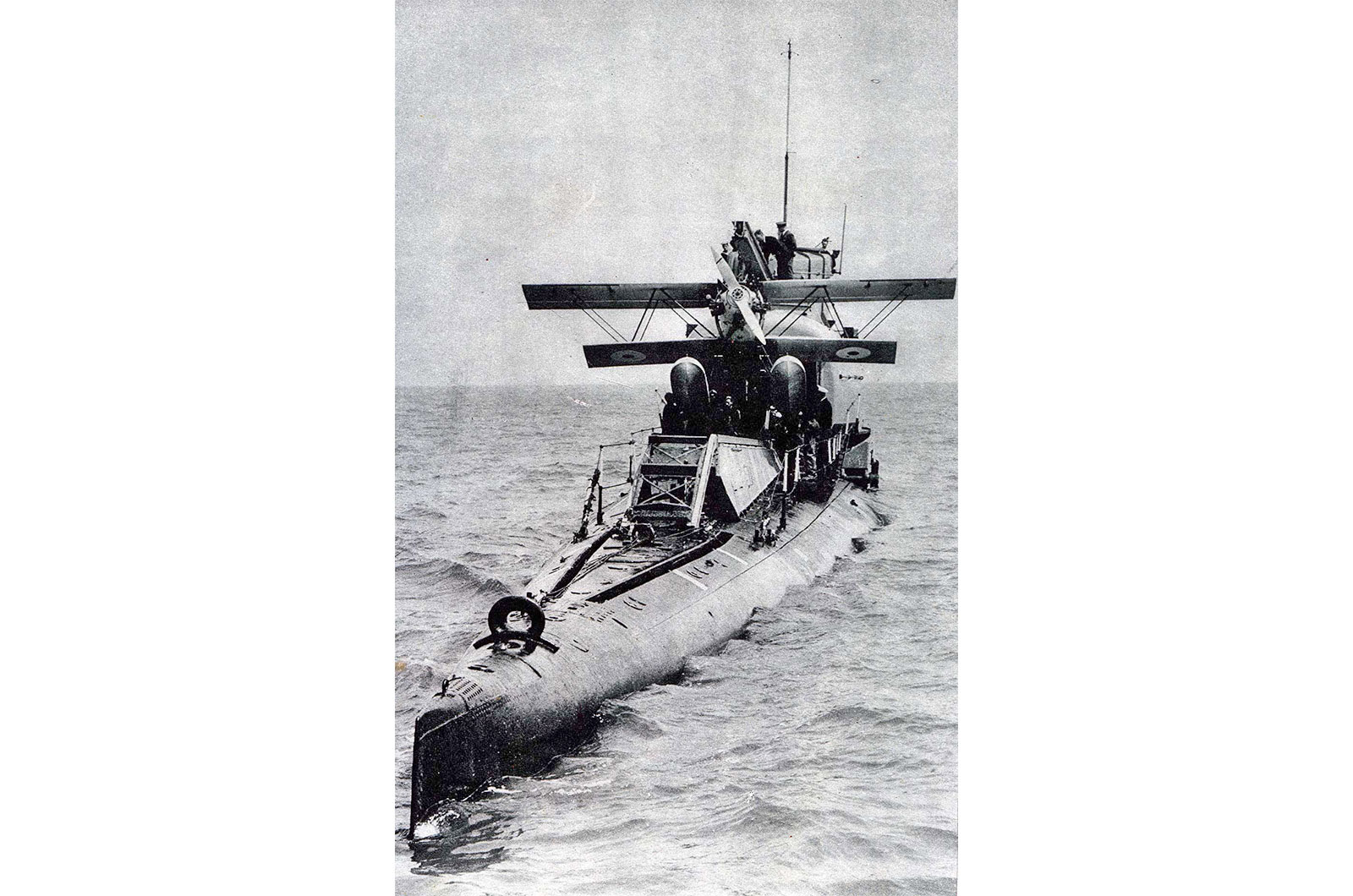

10: Parnall Peto

The Peto was, in its way, an excellent little aircraft but it was the realisation of a terrible idea if not a terrible flying machine. Tragically a single airframe (of two built) directly resulted in the deaths of 60 Royal Navy personnel.

The Peto was designed for a seemingly foolish purpose, to serve as a scout aircraft for a submarine, in this case, the Royal Navy’s largest, the M-class. The concept was also toyed with by the French, German, US and Japanese navies but only Japan pursued it with any seriousness or success.

10: Parnall Peto

A small machine for obvious reasons, the Peto had folding wings and was housed in a watertight hangar immediately ahead of the conning tower. The crew of the M2 were zealous in their attempts to launch the aircraft in the shortest possible time after surfacing.

Probably a little too zealous as it turns out, witnesses on a passing ship, unaware that anything was amiss, saw M2 briefly surface, then submerge forever. When the wreck was discovered the hangar doors were found to be open: in their haste to launch the Peto the doors has been opened too early and the hangar flooded, dragging the M2, the Peto and sixty sailors to the bottom of the sea.

9: Curtiss Seamew

Most of the best aircraft operated by the Royal Navy during the Second World War were of American origin and types such as the Wildcat, Corsair and Avenger dominated Fleet Air Arm (FAA) flight decks for most of the conflict. There were, however, exceptions to this rule and chief amongst them was the appalling Curtiss Seamew.

250 were allocated for British use but only 100 were delivered before the Royal Navy refused to take any more and sensibly demanded Vought Kingfishers instead. It’s not entirely surprising that the USN had tried to offload as many Seamews as possible onto their allies; the Seamew didn’t even win the competition that selected it for service.

9: Curtiss Seamew

A rival design by Vought was judged superior but Vought were busy with the Corsair and Curtiss had spare capacity so into production the Seamew went, and the surprisingly large total of 795 of these unpleasant aircraft were manufactured. If it had been merely slow and uninspiring it could have been written off as a humdrum mediocrity but the Seamew was also dangerous.

Its main fuel tank could hold 300 gallons but it couldn’t take off with more than 80. The engine was prone to failure but even were it to run perfectly it still had other nasty tendencies as, according to the pilot Lettice Curtiss, ‘it was possible to take off in an attitude from which it was both impossible to recover and in which there was no aileron control’

8: Supermarine Seafire Mk XV

The Spitfire’s experience at sea was not a wholly happy one. In the air, the Sea-Spitfire retained all the qualities that had made the regular Land-Spitfire such a successful and popular fighter but revealed that the aircraft was essentially just too delicate for the rigours of operating from a carrier deck.

The Merlin-powered variants were bad enough but the first Griffon-engined Seafires really did not like being on carriers. They had a tendency to veer to the right on take-off, even with full opposite rudder applied, and smashing into the carrier’s island superstructure.

8: Supermarine Seafire Mk XV

Added to this was the unfortunate situation that the undercarriage oleo legs were still the same as the much lighter Merlin-engined Spitfires, meaning that the swing was often accompanied by a series of hops as the oleo could not fully cope with the weight and torque of the aircraft.

The weak undercarriage also conferred on the Seafire XV a propensity for the propeller tips to ‘peck’ the deck during an arrested landing and on some occasions led to the aircraft bouncing over the arrestor wires completely and into the crash barrier. The Canadians and the French replaced these aircraft after very brief carrier service.

7: Westland Wyvern

A perplexing design described by Harald Penrose, Westland’s chief test pilot, as “very nearly a good aircraft”, the Wyvern suffered from the typically British problem of excessive development time, such that it was nudging obsolescence once committed to service.

Part of the reason for this was not the fault of the design at all; the Wyvern had been designed initially to use the Rolls-Royce Eagle, a complicated 46-litre H-block 24-cylinder sleeve valve piston engine (essentially a bigger Napier Sabre) that first ran in 1944 and delivered an impressive 3200 hp.

7: Westland Wyvern

But the Eagle, and later Clyde engine, were cancelled. This left one engine option, the turboprop Python – a woeful engine for carrier use. Slow spool-up time made for sluggish acceleration, and it loved to flame-out during catapult launches. Embarrassingly, the piston-engined Eagle prototype achieved a greater speed and range than its Python-powered production sibling seven years before the Wyvern even entered service.

So saddled with a barely adequate engine the enormous Wyvern attempted to operate from the decidedly small RN carriers of the 1950s. Weighing 295kg (650 pounds) shy of a loaded C-47 Dakota the Wyvern could not be described as ‘light’ and ultimately its main claim to fame derives from its part in the world’s first successful ejection from underwater. Of 127 built, 39 were lost to accidents.

6: Fairey Swordfish

The Swordfish was probably the most successful aircraft the Royal Navy has ever operated. If it had achieved nothing else, the attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto in 1940 would have ensured the Swordfish’s immortality yet it also crippled the German battleship Bismarck and operated throughout the war.

The Swordfish were straightforward – it was reliable, simple and easy to fly. It made for an excellent training aircraft but then so did its cousin, the Fairey Battle which regularly features in lists of the worst aircraft. Yet the Battle was better armed, longer ranged and much faster than the poor Swordfish. The Swordfish was appallingly slow, not very manoeuvrable and effectively defenceless when faced with even the worst fighter aircraft.

6: Fairey Swordfish

It is telling that in all its most famous successes the Swordfish never faced an enemy aircraft of any kind: it simply couldn’t. Bismarck had no air cover and the Taranto operation was flown at night. By contrast, in February 1941 all of the Swordfish force sent to attack the German battleships engaged in Operation Cerberus, the so-called ‘Channel Dash’, were destroyed by fighters or flak. Of the eighteen aircrew involved, only five survived.

It was dangerous to operate even a powerful anti-shipping aircraft such as the Beaufighter in European waters until the very end of the war, in a Swordfish it was effectively suicidal. Ultimately the success the Swordfish experienced was due to a combination of extremely canny tactical deployment by the Navy and the exceptional heroism and skill of its aircrews, not through any outstanding combat quality of the aircraft itself.

5: de Havilland Sea Vixen

Had it entered service with the RAF in the early fifties de Havilland’s last fighter would be remembered as a great aircraft. But it didn’t and the Sea Vixen turned out to be a death trap. 145 Sea Vixens were built, of these 38% were lost over the type’s twelve-year operational life. More than half of the incidents were fatal.

The Sea Vixen entered service in 1959 (despite a first flight eight years earlier), two years later than the US Navy’s Vought F-8 Crusader. The F-8 was more than twice as fast as the Sea Vixen, despite having 3,000Ibs less thrust. The development of the Sea Vixen had been glacially slow.

5: de Havilland Sea Vixen

The specification was issued in 1947, initially for an aircraft to serve both the Royal Navy and the RAF. The prototype flew in 1951, and one crashed at the Farnborough airshow the following year. This slowed the project, and the RAF ordered the rival Gloster Javelin, whilst DH and the RN focused on the DH.116 ‘Super Venom’. This project was substantially redesigned to navalise it.

All of which meant it arrived way too late, as is compulsory for all British postwar aircraft. Meanwhile, its peer, the F-8, remained in frontline service until 2000, and its other contemporary, the F-4, remains in service today. The Sea Vixen retired in 1972. 51 Royal Navy aircrew were killed flying the Sea Vixen.

4: Blackburn Firebrand

Though good-looking, the Firebrand was a pilot-killer. The specification for the type was issued in 1939 and it first flew in 1942 but did not enter service until after the war had ended. Despite this luxuriously long development, it was an utter pig, with stability issues in all axes and a tendency to lethal stalls.

There was a litany of restrictions to try and reduce the risks, including the banning of external tanks, but it still remained ineffective in its intended role and dangerous to fly. Worse still, instead of trying to properly rectify the problems, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) started a witch-hunt of those pilots who dared to speak the truth about the abysmal Firebrand.

4V: Blackburn Firebrand

Test pilot Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown, had this to say on the Firebrand: “it was a disaster and it was incapable of fulfilling competently either the role of torpedo-bomber or that of fighter, but it was built like a battleship – and there were to be those that would say that it flew like one”.

Even so, somehow it managed to remain in service until 1953, double the length of time achieved by its successor, the similarly benighted Wyvern.

3: Blackburn Roc

In the 1930s there was a fashion for ‘turret fighters’. Carrying their steerable guns in rotatable turrets greatly increased the angular coverage compared to fixed guns, but they came at a huge cost in terms of extra weight and drag. Described as “a constant hindrance” by the commander of 803 squadron the Blackburn Roc turret fighter was an unhappy outgrowth of the mediocre but adequate Skua.

The Roc essentially comprised the Skua’s airframe but saddled it with a gun turret weighing about a ton and adding enough drag to lower the speed of the already pedestrian Skua by some 30 mph. A maximum speed (at sea level) of 194 mph was simply suicidal for a fighter facing Luftwaffe Bf 109s. Add terrible agility, no forward-firing guns and you get the idea.

3: Blackburn Roc

Wisely, the military decided the best use for it was as a static machine-gun post but not before the Roc had seen some action and scored one confirmed kill. Remarkably the Roc’s sole victim was a Junkers 88, an aircraft capable of flying over 100 mph faster than the lumbering Roc.

2: Supermarine Scimitar

Supermarine created the war-winning Spitfire, and it was continually upgraded throughout the War under the capable leadership of the English designer Joe Smith. Though Smith was a master of the piston-engined fighter plane, his endeavours in jet propelled fighters were far less impressive.

The Scimitar was a case of too much too soon and its shortcomings were paid for in pilot’s lives. It suffered an appalling attrition rate of 51 per cent yet was a worse fighter than the Sea Vixen and a worse bomber than the Buccaneer. To add insult to injury it was also extremely maintenance heavy.

2: Supermarine Scimitar

Nonetheless, the Royal Navy gamely took the Scimitar, an aircraft so dangerous that it was statistically more likely than not to crash over twelve years, and armed it with a nuclear bomb. Prior to this one example crashed and killed its first Commanding Officer in front of the press. The Scimitar was certainly not Joe Smith’s finest moment.

It was the last FAA aircraft designed with an obsolete requirement to be able to make an unaccelerated carrier take-off, and as a result had to have a thicker and larger wing than would otherwise be required. Only once did a Scimitar ever make an unassisted take-off, with a very light fuel load and no stores, and then just to prove that it could be done.

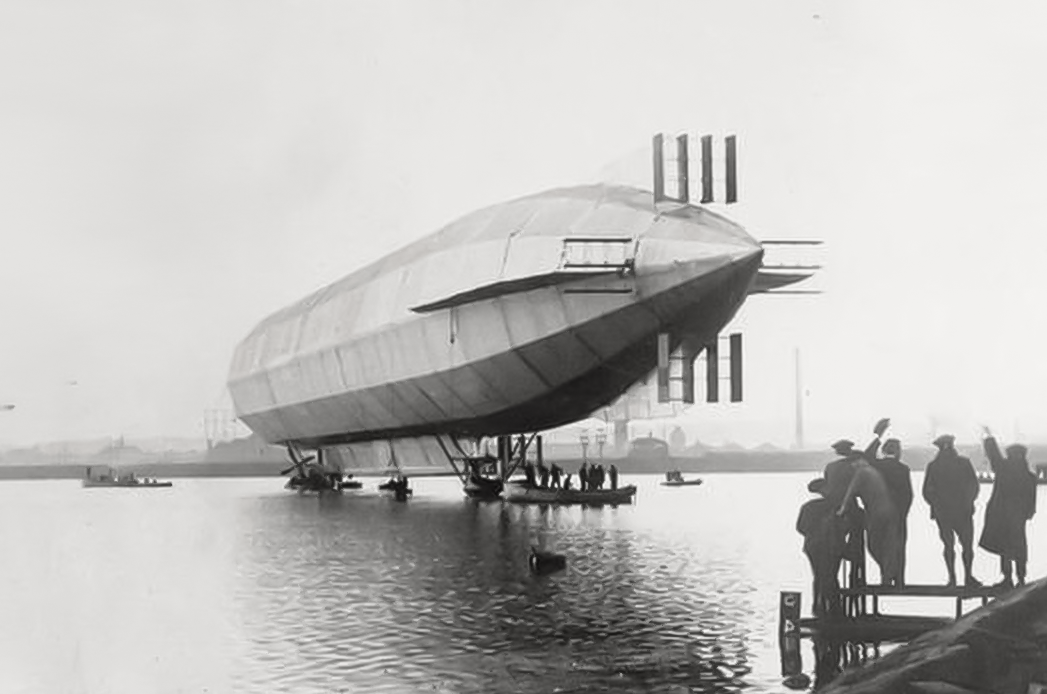

1: His Majesty's Airship No. 1 ‘Mayfly’

Naval aviation started badly in the UK. In 1909, inspired by German Zeppelin developments, which despite their later fame as bombers were originally intended to operate as long ranged Naval scouts, the Royal Navy commissioned Vickers, at great expense, to build the world’s finest airship, intended to carry 20 crew in considerable comfort and capable of cruising at 40 knots (46 mph) for 24 hours.

Sometime before trials were to be attempted the airship’s crew started training and it was charmingly noted ‘They lived on board the airship and suffered no discomfort at all although no provision had been made for cooking or smoking on board’. Over the course of the following year static trials were carried out and it was realised that the ship was too heavy.

1: His Majesty's Airship No. 1 ‘Mayfly’

There followed a series of cack-handed modifications which reduced the weight of the aircraft by three tons. Gone was the water recovery system along with half the aerodynamic control surfaces and, most seriously, the external keel of the airship. This last modification was strongly objected to by a draughtsman from Vickers called Hartley Pratt who claimed it would prove disastrous but his warnings were ignored and he left the company.

The airship was being removed from its floating shed in a light wind on the 24 September 1911 when cracking sounds were heard from amidships and it broke in two. The 156-metre-long aircraft had never flown, which was lucky, given its dangerously weak structure. As it was no one had been even slightly hurt in what was probably the least dramatic air crash of all time. Even without provision for cooking or smoking, His Majesty’s Airship No.1 had ultimately proved more successful as a house than as a flying machine.

Follow Hush-Kit's incredible aviation stories on Substack and X

If you enjoyed this story, please click the Follow button above to see more like it from Autocar

Photo Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en

Add your comment