Helicopters often have a bad reputation for safety or performance, which is generally unfair.

However, some helicopters deserve to be flagged up for their failings. Unfortunately, the ten aircraft in this story have let the side down and are generally poorly designed, used for the wrong role, overly ambitious, or some combination of all three. In defence of some of these accursed choppers, they were all ahead of their time, and often pioneered new technologies. Let’s meet the 10 worst helicopters:

10: Petróczy, Kármán and Žurovec tethered helicopters

Today, small uncrewed drones powered by rotors or fans are a common sight on the battlefield. In addition to the attack role, their primary mission is carrying out battlefield reconnaissance, and it’s fascinating to learn that this basic idea is over 100 years old. However, it took a very long time for this technology to mature.

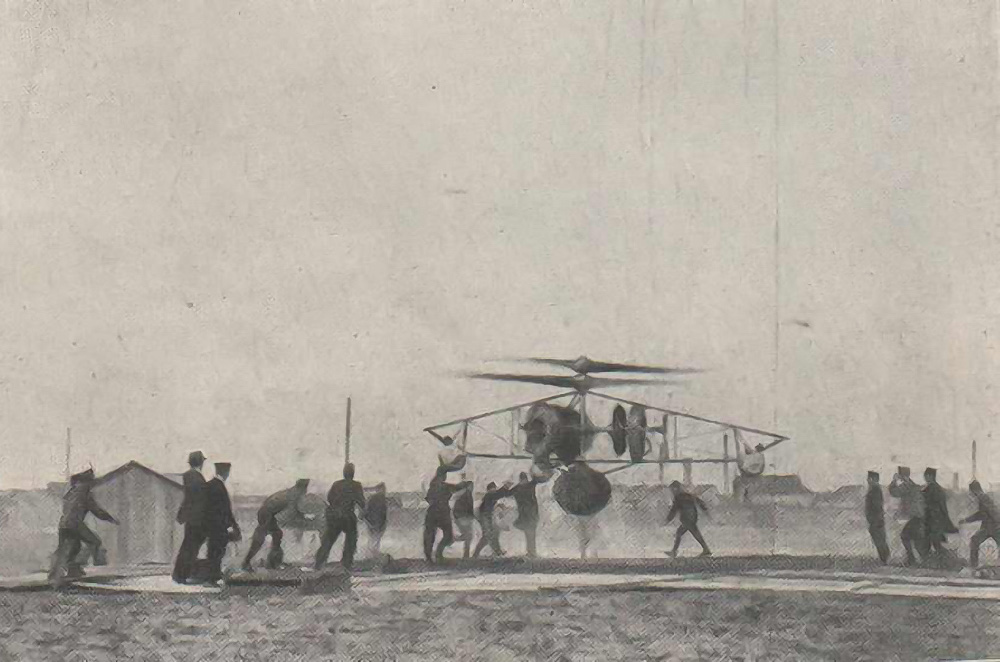

Petróczy, Kármán and Žurovec were engineers who worked developing observation helicopters for the Austro-Hungarian empire both before and during the First World War. At this time, the primary method of aerial observation on the battlefield was the balloon. Hydrogen balloons were dangerous, and Petróczy, Kármán and Žurovec believed they had a superior alternative.

10: Petróczy, Kármán and Žurovec tethered helicopters

The PKŽ helicopters relied on twin contra-rotating rotors to counter torque. The PKZ-1 was powered by a single Austro-Daimler electric motor, the PKZ-2 initially by three Gnome rotary engines of 75 kW (100 hp). When the PKZ-2 was found to be underpowered, the engines were replaced with le Rhone rotary engines of 89 kW (120 hp).

On 10 June 1918, the PKZ-2 was demonstrated to officials, despite Žurovec’s doubts about the reliability of the le Rhone engines. He was right to worry, as when the engines spluttered out, the tether handlers understandably panicked, causing a crash-landing, damaging the craft and snapping the rotors.

9: Hiller YH-32 Hornet

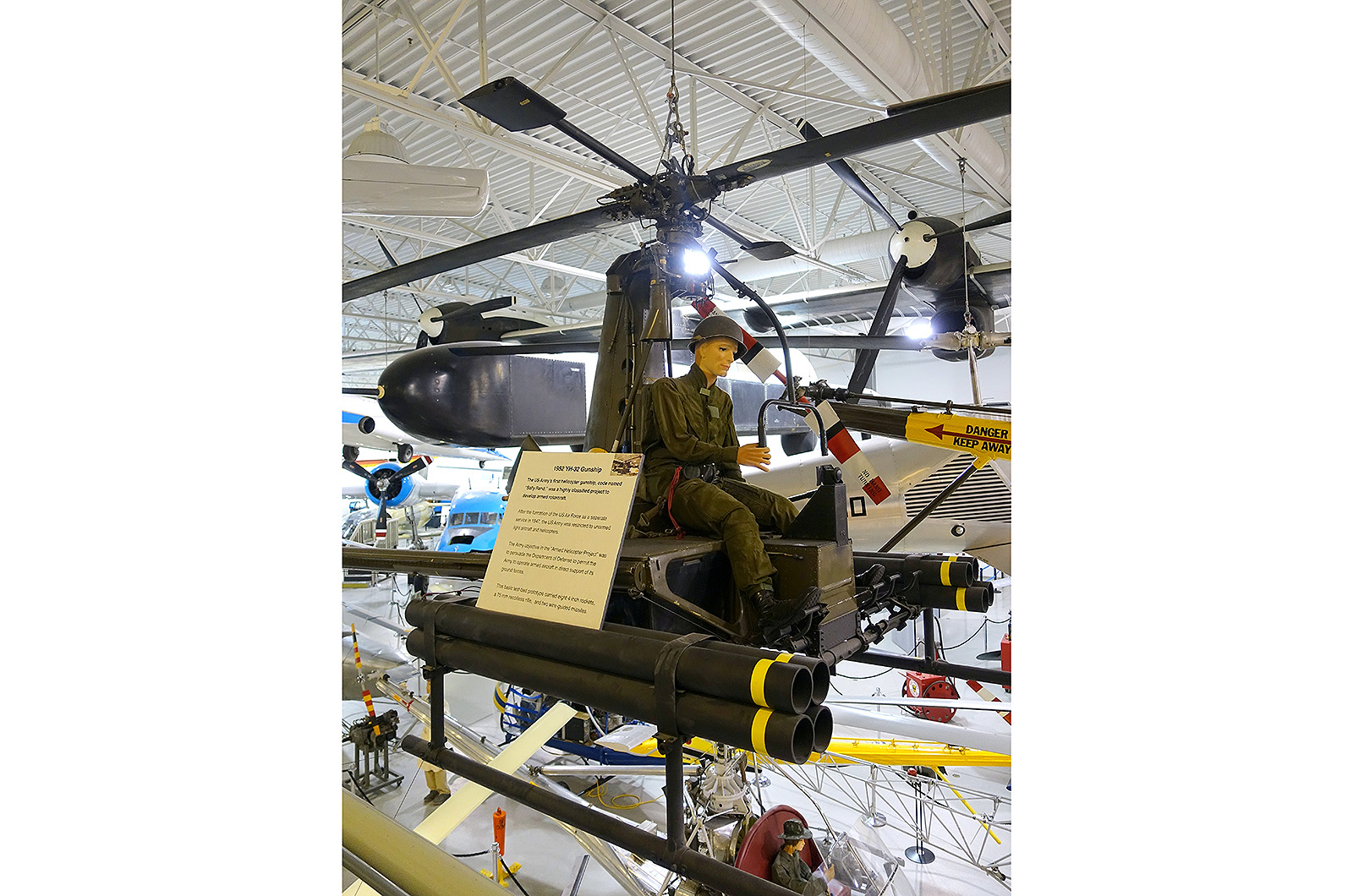

Helicopters are complex machines, but replacing the transmission system and piston (and later turbine) engines with tip ramjets created a far lighter, more straightforward solution. Indeed, the Hornet enjoyed 90 horsepower (68kW) from two ramjets mounted on the rotor tips, which each only weighed 13 pounds (5.9kg).

The ramjet is the simplest form of jet propulsion as it doesn’t require fans, just the speed of the air itself. Unfortunately, ramjets are also incredibly noisy and thirsty. Though its terrible range made the H-32 an impractical vehicle for military operations, it did much to pioneer US helicopter gunships.

9: Hiller YH-32 Hornet

Intriguingly, some consider the YH-32A, nicknamed the Sally Rand (as it was "stripped to the bare essentials" like the Burlesque performer Sally Rand), the first helicopter gunship. Three YH-32As were tested in 1957 with various armaments including combinations of rockets, guided missiles, land-mine detectors, and even a 75mm recoilless cannon.

Despite the inherent issues of tip-jets, many tip-jet helicopter types have been built (or seriously considered), including the Avimech Dragonfly DF-1, the Dornier Do 32, Dornier Do 132, the Fiat 7002, Percival P.74, Sud-Ouest Ariel, Sud-Ouest Djinn and VFW-Fokker H3.

8: Hughes XH-17

The XH-17 also featured tip-jet-driven rotors. But this point, any similarity with Hiller’s rather dainty helicopter ends, as the XH-17 was a massive beast. Starting life as a rotor test rig under the auspices of the Kellett Aircraft Corporation, the XH-17 ducted bleed air from the compressor sections of two GE J35 jet engines.

After travelling 65 feet to the ends of the oversized rotor blades, fuel was added to the airflow and ignited, producing four distinct jet plumes in the trailing edge…and a noise signature like an AC/DC concert, complaints being received from eight miles away.

8: Hughes XH-17

Facing financial issues, Kellett sold the XH-17 and their interest to the Hughes Aircraft Company. The first intentional flight took place, in 1952, when the XH-17 bounced wildly up and down. After some tinkering, Hughes managed to resolve the control issues, and the XH-17 entered an intensive 10-hour test programme, at which point the rotor’s fatigue life was used up.

Although there was a proposal for a four-bladed production version of the XH-17, the XH-28, the Army eventually decided not to pursue it. There was presumably not a massive requirement to move tanks across the battlefield at 80mph while being heard by everyone for many miles around.

7: Percival P.74

1950s were a time of great advances in aviation; the Percival P.74 was responsible for none of them. Looking as if the company’s designers were tasked to make a workable helicopter from a drawing by a three-year-old child, it featured a bulbous fuselage with tiny wheels and a comically out of proportion tail rotor.

Presumably feeling there was nothing left to lose it was decided to power it by using tip-jets to drive the rotors and control their pitch with trailing edge ailerons. The observant reader will notice both these features have failed to make it into widespread production today...

7: Percival P.74

To provide air for the tip jets, two Napier Oryx gas turbines drove air compressors, the combined exhausts from both turbine and compressor then being ducted to the rotor tips. As someone had decided to put the engines in the belly this involved large ducts of hot air going up either side of the cabin, splitting it in two.

They probably kept it warm, though. More worryingly, the only access to the cockpit was through the gap between these ducts, the sole door being at the back of the aircraft. This rather comical loser should not detract from Percival’s better aircraft, like the excellent, and exceptionally beautiful Mew Gull racer of the 1930s.

6: Agusta A106

When the British Westland Wasp carried the rather alarming WE177A nuclear depth charge, it needed to remove its doors to meet the range requirement. Despite this, the Westland Wasp avoids being on this list because it is probably the only Anti-Submarine Warfare helicopter to have damaged a submarine, making you wonder what the rest of them have been doing with their time.

With a maximum take-off mass lower than the Wasp’s empty weight, the A106 was truly small; at 1400kg fully loaded, it weighs less than most cars today. This weight was achieved by only providing seating for one pilot, while two Mk 44 torpedoes could be hung under the fuselage, at this point, you must ask how much of the 800kg payload remained available for fuel.

6: Agusta A106

The absence of any other crew would have limited the A106 to carrying its payload where it was told to and then dropping it. Hopefully someone is available to tell the pilot how to get back as well, as photos of the cockpit show it to be remarkably lacking in avionics.

It’s at this point you start to wonder if Agusta realised they had created a crewed version of the QH-50 DASH torpedo-carrying drone, which had already entered service two years before the 106’s first flight in 1965. In the end only the two prototype A106s were built.

5: Westland 30

It’s the late ‘70s, and Westland is having success with its Lynx maritime attack helicopter. The next obvious move was to build on that by making a civilian version for the offshore and VIP market. Obvious, that is, if you’re not familiar with the Lynx, which is an ergonomic and audible nightmare, with average endurance, and a maintenance hours per-flying-hour problem.

The Westland 30-100 used the same rotors, engines and transmission as the Lynx but mated it with a boxier fuselage which could apparently seat 22. Which would have been a claustrophobic experience if sitting in the back of a 9-passenger configured Lynx is anything to go by.

5: Westland 30

The Westland 30 was also a heavy aircraft of almost 6000kg, a figure the Lynx wouldn’t get close to until the Mk 8 in the mid-90s. This didn’t do anything for the performance, the early Gem engines not being up to the task. Consequently, the WG30 was poor in range, power, and operating costs. On the plus side, it meant it rarely flew with more than about 10 people in the back, which must have made it quite roomy.

After two fatal crashes in 1988 and 1989 the fleet was grounded. Meanwhile, operators in the USA seemed no more enamoured of them with issues around the auto-stabilisation system, the maintenance levels required, and the lacklustre of customer support, issues that wouldn’t have surprised any Lynx operator.

4: Mil Mi-10 'Harke'

The Mi-6 combined a brilliantly eccentric aesthetic with being the world’s largest production helicopter. It was a truly glorious machine, and the lack of a nose-mounted conservatory in its successor, the Mi-26, leaves us all the poorer. The Mi-10, on the other hand, was a flying crane derivative of the Hook, which failed to live up to the glory of its older sister.

Removing the bottom half of the fuselage the resulting gap between the aircraft and the ground was filled with a stalky 3.75 metre tall, 6-metre-wide undercarriage. For reasons to do with helicopter aerodynamics, the right-hand legs were 300mm shorter than the left. Having built possibly the most ridiculous-looking landing gear known to man, there must have been some disappointment when it was found to shimmy while ground taxiing.

4: Mil Mi-10 'Harke'

It was discovered that underslung loads were problematic due to the poor view from the cockpit even when using the CCTV system. Realising the requirement to carry a bus or prefab building underneath the fuselage wasn’t very useful, the later Mi-10K featured a two-metre shorter undercarriage and a second aft-facing cockpit underneath the first.

This made it much better for carrying underslung loads up to around 11,000kg in weight. Or about what you could get inside a Mi-6. This probably explains why only 55 or so Mi-10s were built in total; there are only so many times you need to move something you can’t get in or under a hook.

3: Yakovlev Yak-24 'Horse'

As part of a Stalin ‘inspired’ post-war rush to revive helicopter development, Yakovlev were ‘invited’ to design a heavy lift helicopter. The task seemed simple: make a boxy fuselage to put everything in and put a rotor at each end to lift it off the ground. As with most things helicopter-related, it turns out nothing is that simple.

Power was to be provided by the same Shvetsov Ash-82V engine, gearbox, and rotors as used in the Mi-4 Hare, except two of them. Presumably, due to sanity issues, one was placed just above the loading ramp, and the other was tilted over and squeezed behind the cockpit.

3: Yakovlev Yak-24 'Horse'

To stop the blades from clashing, a synchronisation shaft connected the two gearboxes and allowed power to be transferred front to rear, or vice versa, in the event of an engine failure. Outside of this list, this has not proved a popular configuration.

The first indication that everything may not be right with the Horse came during ground testing when the rear rotor vibrated itself and its gearbox free and committed seppuku by ripping the fuselage apart. Further trials revealed that behaving like a tumble dryer with a brick in it was a feature of the Yak-24 that it might be an idea to design it out.

2: Bristol Belvedere

Failing to sell the helicopter to the Royal Navy as an Anti-Submarine Warfare aircraft, Bristol didn’t see any reason to radically change their design. So, they didn’t and sold it to the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a transport helicopter instead, despite a massively tall undercarriage designed to accommodate torpedoes. To be fair the RAF don’t seem to have thought to ask for any changes either.

This left troops trying to board through a door four feet off the ground as the fuselage was still high enough to allow torpedoes to be loaded on the underside. Which turned out not to be a major requirement in the jungles of Borneo due to the paucity of submarines. Taking a leaf out of Yakovlev’s book, Bristol put the engines at either end of the cabin.

2: Bristol Belvedere

Going one further, they positioned the rear one in the fuselage, precluding the use of a loading ramp. Meanwhile, the one at the other end blocked access to the cockpit, which was probably a smart move but was ultimately defeated by installing a bulge on the left of the fuselage.

To make matters more interesting for the pilot the engines were started with AVPIN a substance which helpfully doesn’t need oxygen to burn and will happily do so if mishandled. This left them with the choice of squeezing back past the on-fire engine compartment or jumping to the ground and breaking an ankle.

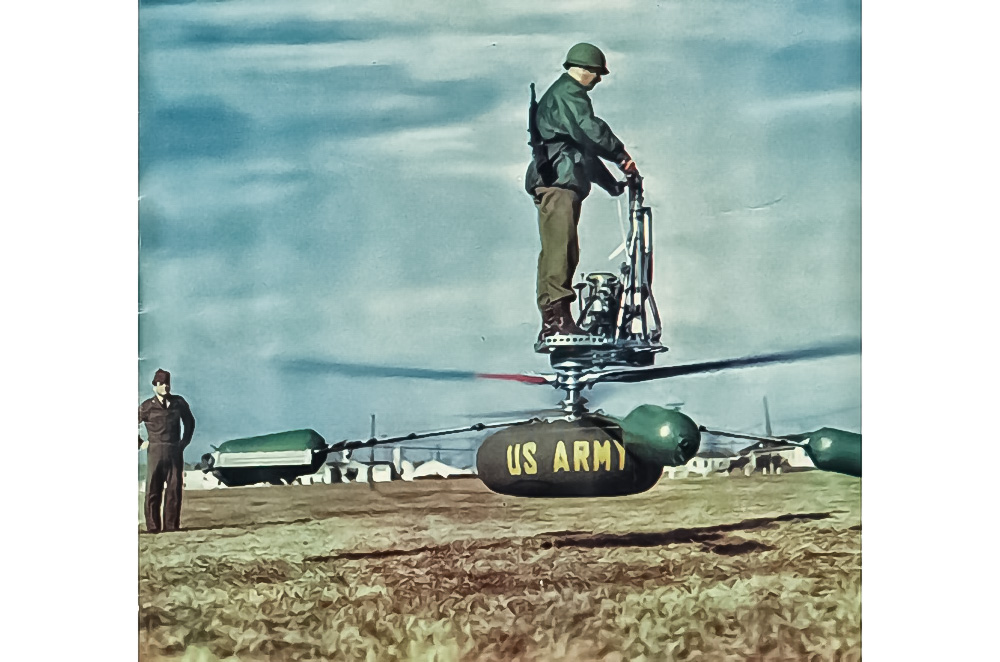

1: De Lackner HZ-1 Aerocycle

This is almost definitely a helicopter and was evaluated by the US Army as part of their plans to kill their own soldiers in new and imaginative ways. Eschewing such fripperies as a fuselage, seats, or actual controls, the HZ-1 was steered by the ‘pilot’ leaning in the direction he wanted to go.

For those wondering if they can build one in their own garage, the most complicated bit, the engine, was a converted Mercury outboard motor so the answer is probably yes. This drove two 15’ diameter contra-rotating rotor blades that, in two fingers to occupational health and safety, were placed below the sacrificial offering.

1: De Lackner HZ-1 Aerocycle

In the defence of the HZ-1, in trials, soldiers learnt to fly it with only twenty minutes of instruction before speeding across the landscape at up to 75mph. Although, with a range of only 15 miles it’s not immediately apparent that the turn of speed was particularly useful.

In the cons column, the HZ-1 suffered two (apparently non-fatal) accidents where the contra-rotating blades clipped each other and stopped working. More worryingly, NACA was unable to repeat the phenomena in their wind tunnel, proving that even rocket scientists don’t understand helicopters. Combined with a moment of sanity, the US Army realised there wasn’t a lot of utility to the personal helicopter idea, which led to the end of the programme.

Follow Joe Coles and his Hush-Kit aviation world on Substack and X

If you enjoyed this story, please click the Follow button above to see more like it from Autocar

Photo Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en

Add your comment