At the start of each British Touring Car Championship race, something like 13,000bhp is unleashed before an excited crowd. Engine builders, although quietly confident, may admit to the odd flutter of butterflies, too, because their efforts are vital to every driver’s chances of success. Since 2011, when BTCC organiser TOCA established the New Generating Touring Car (NGTC) rules, teams have been able to use a race-prepared factory engine or a generic TOCA unit supplied by Swindon Powertrain. All use an Xtrac six-speed sequential gearbox no matter their engine choice.

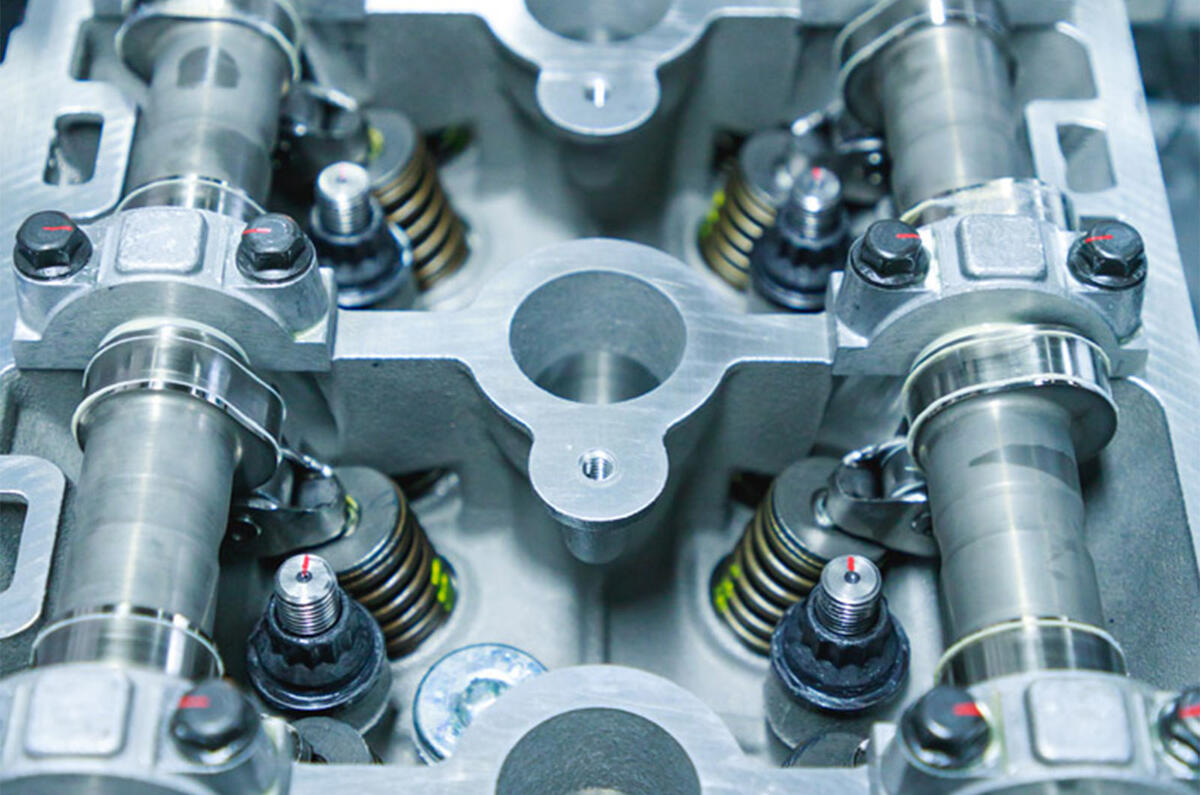

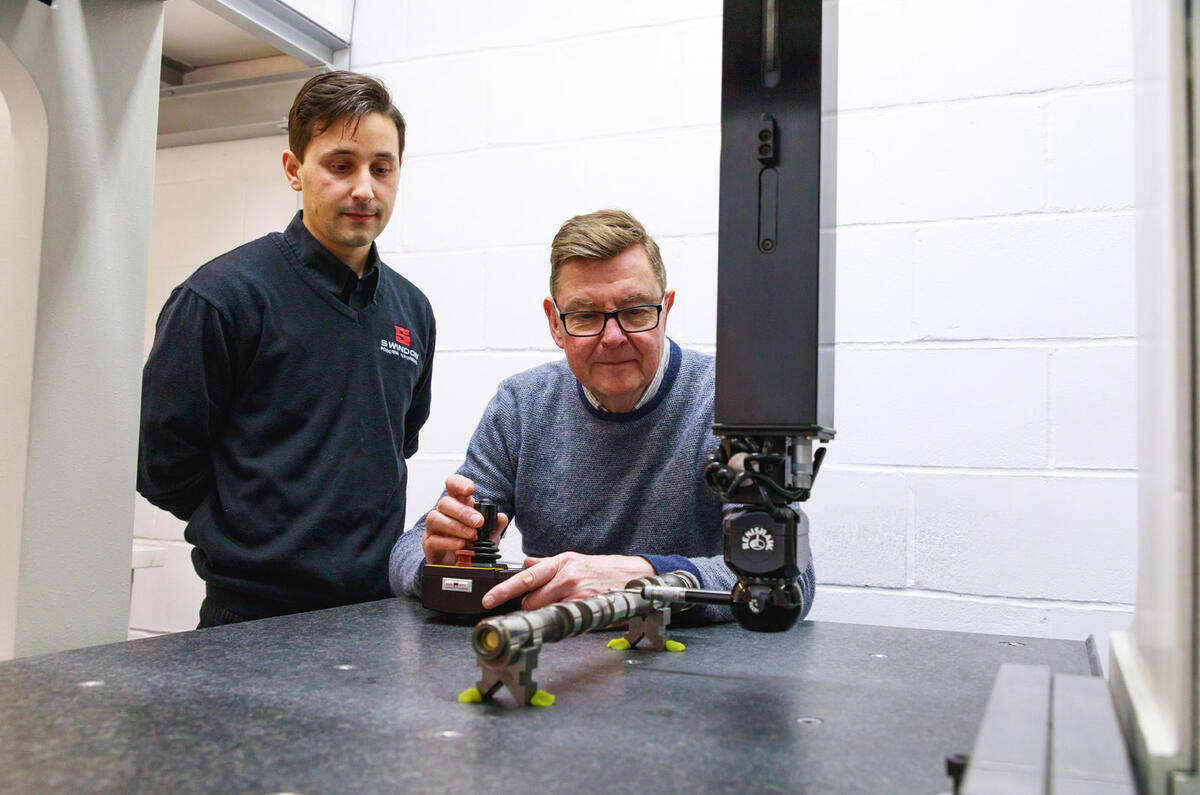

The ‘unbranded’ TOCA engine is based on a standard 2.0-litre, direct-injection, 16-valve, turbocharged four-cylinder engine purchased from a major road car maker. Swindon has built nearly 200 examples since 2011, each one taking around 45 hours to complete. The race engines are equipped with ‘drive-by-wire’ electronic throttles under the control of a Cosworth ECU that every car must use, although engine builders can modify the mapping.

Power is quoted by TOCA as 350bhp-plus, but Swindon says they’re technically capable of 400bhp and Maxed Racing gives the output of its Vauxhall Astras as ‘around 380bhp’. The engines have a life of 5000km (3100 miles) between services and will cover 3500km (2174 miles) in a season. Installation in the car can be either transverse or longitudinal in order to suit both front-wheel drive and rear-wheel drive.

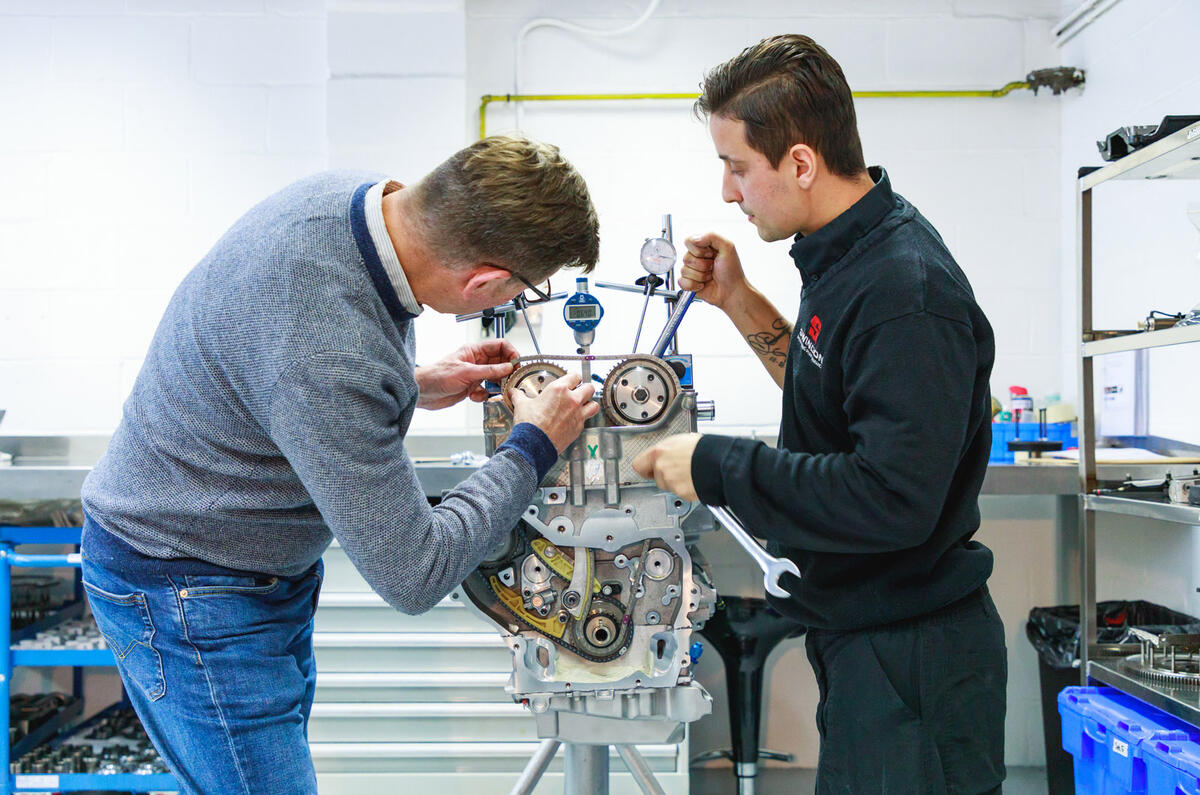

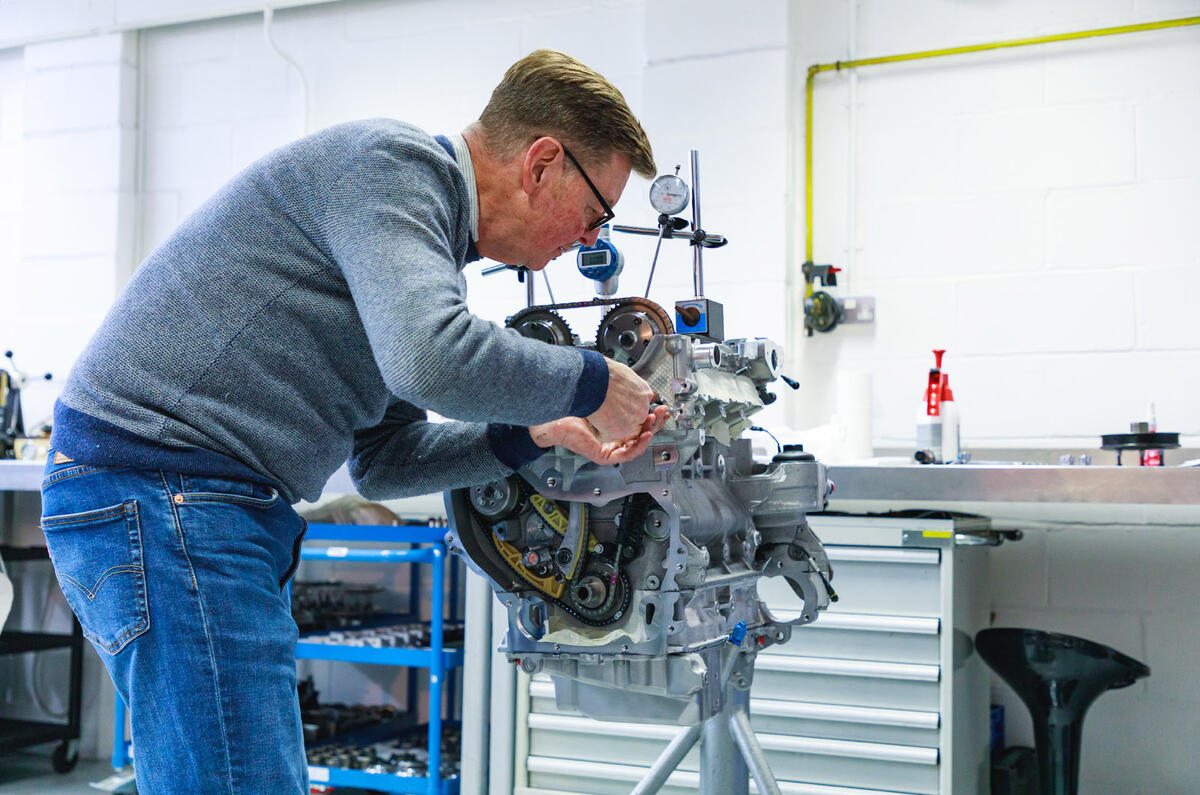

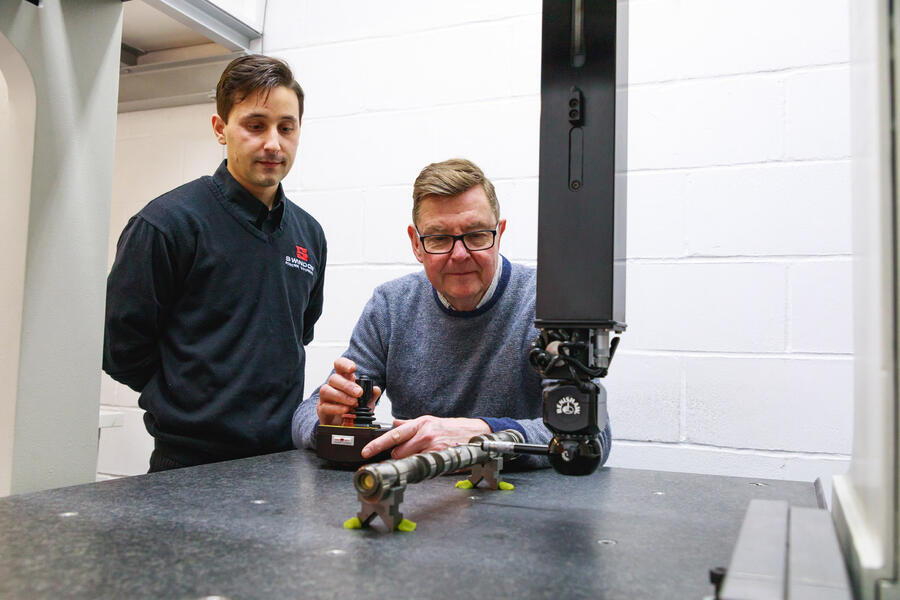

The great thing about writing a story on race engine building is the chance to get your hands dirty – except I don’t, because everything in Swindon’s engine shop is so clean. There isn’t time to help with an entire 45-hour build, but I do have a crack at a couple of crucial stages.

First off is checking the clearance on the crankshaft main bearings (which support the crankshaft in the crankcase) and on the big-end bearings (which attach the connecting rods with their pistons) to the crankshaft. This clearance is crucial. Too tight and the bearings could fail catastrophically, too loose and they would wear prematurely with potentially the same end result.

With engine builder Tiago Lopes instructing and watching my every more, I check the clearances with Plastigauges, which look like thin threads of plasticine. When a short length is laid across each bearing journal and its cap tightened to the correct torque, the Plastigauge gets squashed flat. Measuring its flattened width against a scale gives the clearance in the bearing.

ARP competition bolts are much stronger than standard ones, which aren’t up to dealing the massive forces exerted in a race engine. I follow instructions to the letter, doing everything by the Swindon book. For example, slippery bolts are removed with a magnet rather than your fingers to avoid dropping them onto the finely ground bearing surface of a crank journal or into the engine, and threads on the connecting rods are covered with plastic tubes during the process to avoid damaging the crankshaft.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Why not the same cars?

Why not the same cars?

Base engine?

It would be interesting to know which manufacturer supplies this standard base engine - also which manufacturers use their own units in the series? Presumably the standard ECU is designed to ensure horsepower parity between all engines.