There aren’t many cars in existence today that were built a century ago.

Yet, incredibly, Autocar was last week informed that a car we had written about on 29 December 1917 has survived - and remains, unrestored, in perfect condition.

Almost as unbelievably, this is not a Vauxhall Velox or a Morris Oxford, but a “most ingeniously made model of a chassis which in full size would be of about 100hp, and was made from any odd bits of metal upon which the constructor, a British officer now a prisoner of war in Germany, could lay his hands in the prison camp where he is confined at.”

This officer was Colonel John HT Icke. Born in 1888 in colonial South Africa, he moved to the UK in 1901 and, at the outbreak of the Great War, joined the South Lancashire Regiment. He was captured by the Germans very early on, having been a member of the original British Expeditionary Force, which was sent to the Western Front in France in 1914.

In 1917, he was able to get hold of an ‘itinerant photographer’, as per our original article, and sent the photographs and information back to a friend of his in Britain.

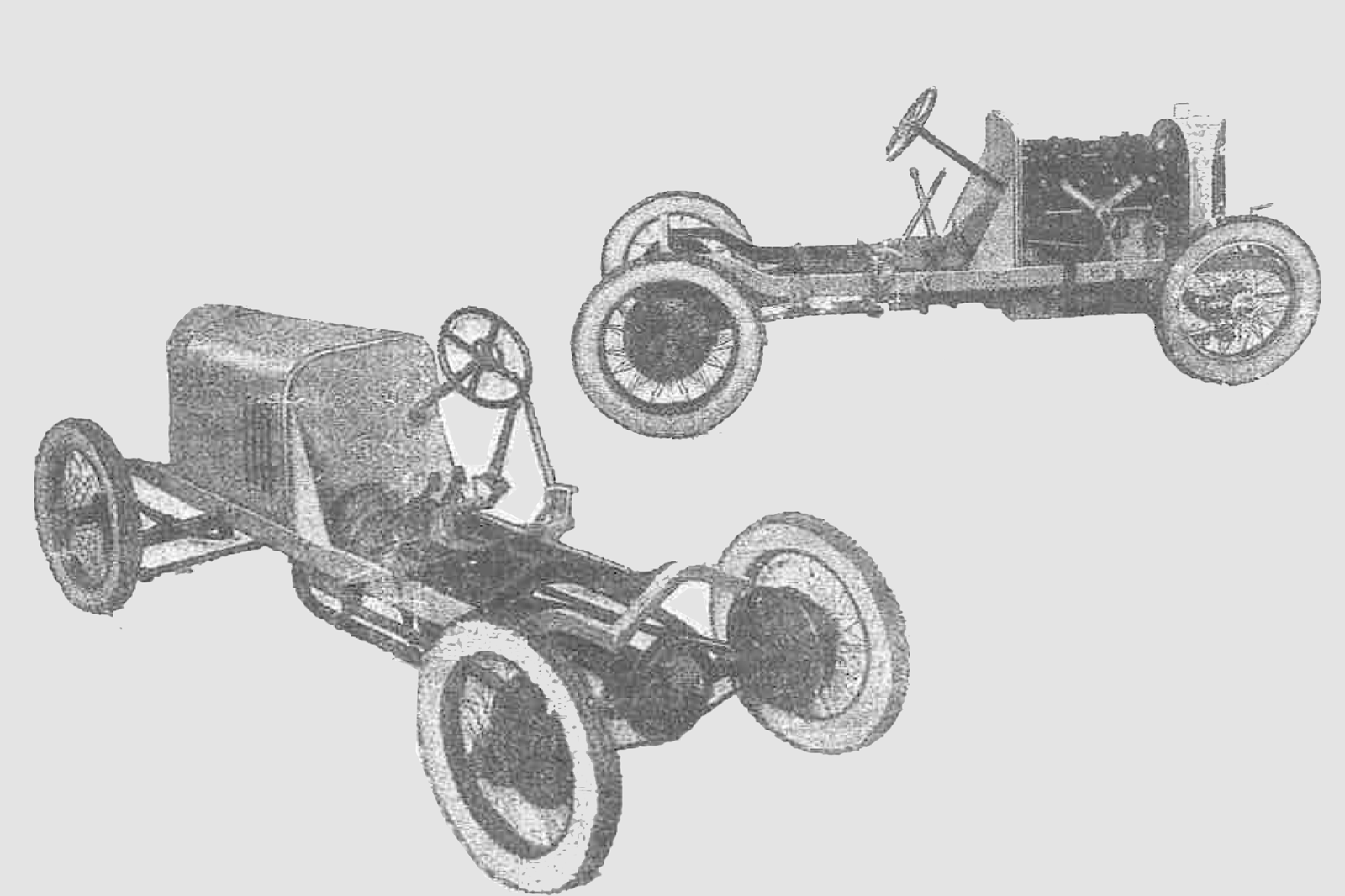

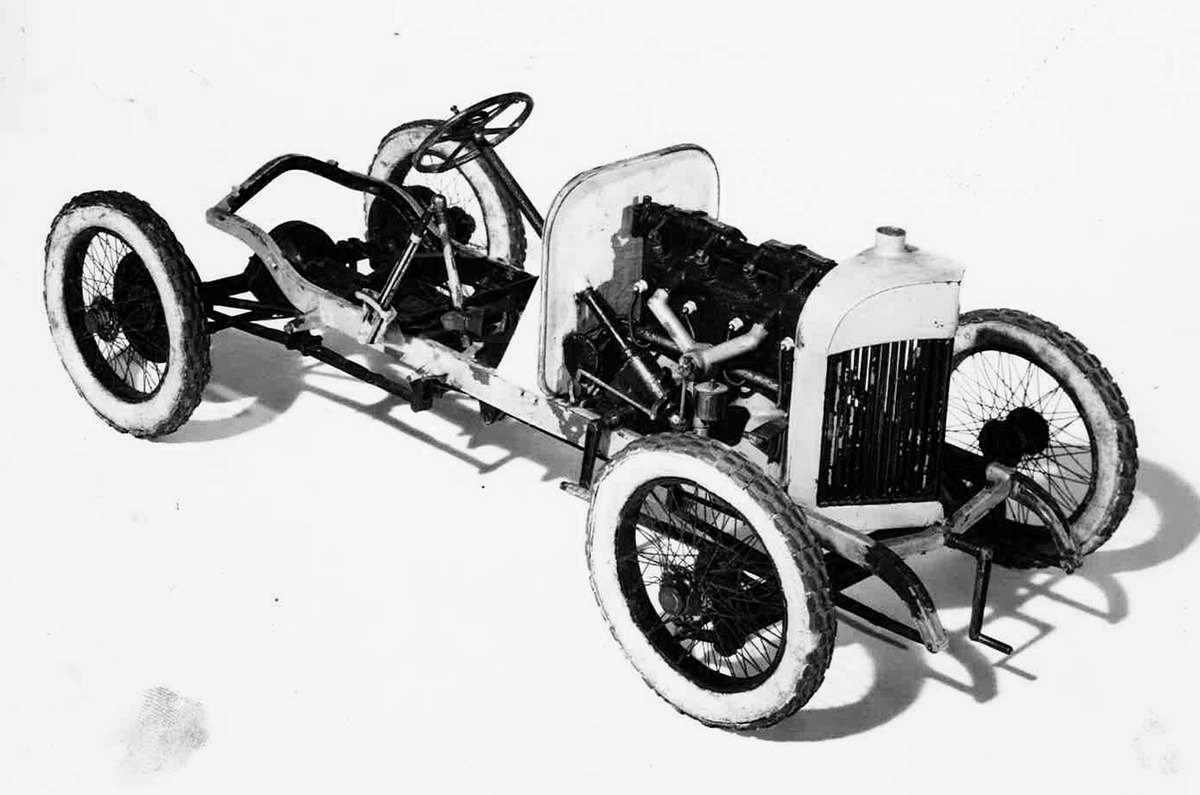

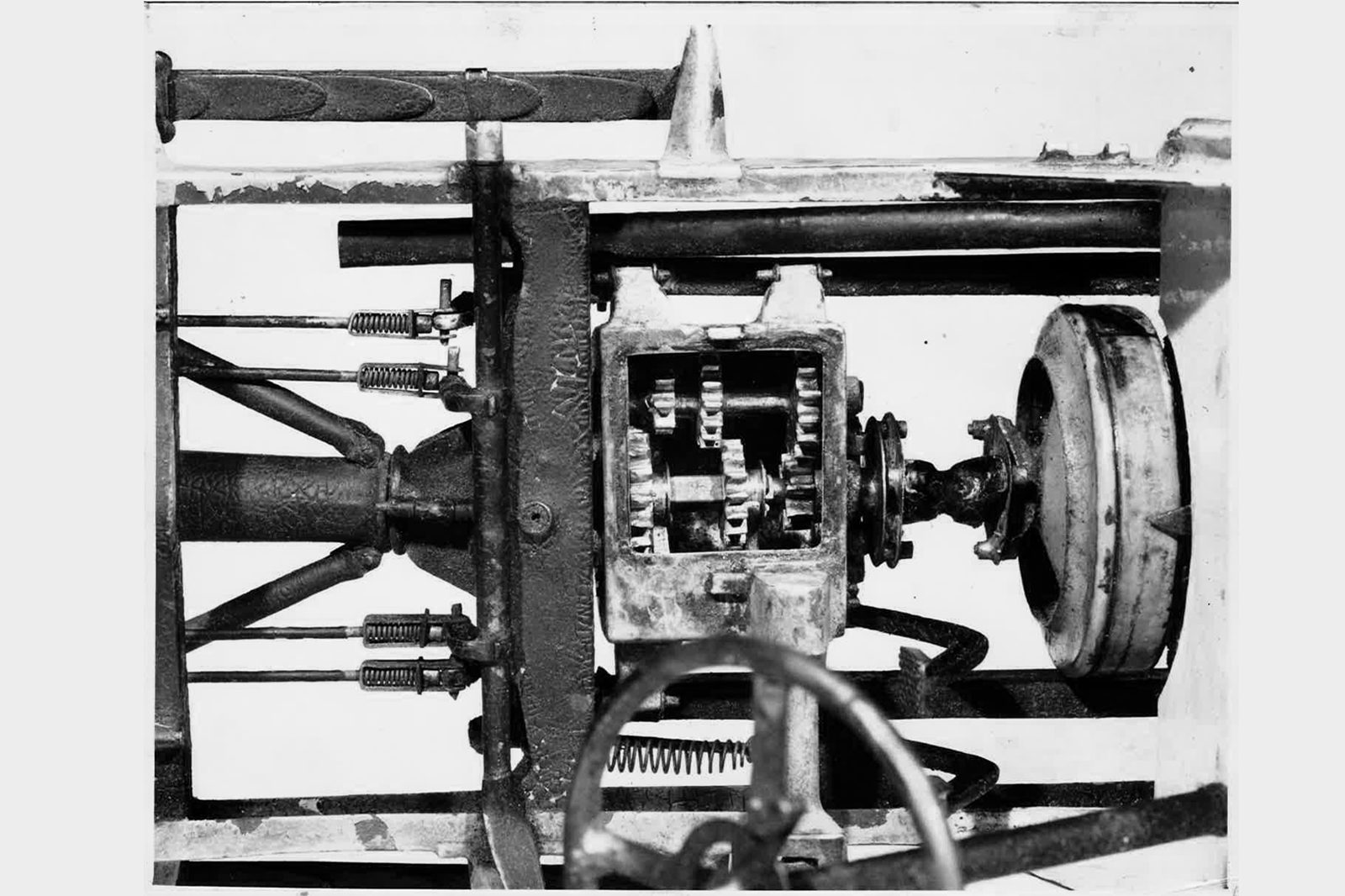

“In view of the fact that all but two parts are made to operate, it is not difficult to imagine that many hundreds of hours of patient and expert application have been necessary to finish this model,” Autocar said.

“As the photographs show, it is no caricature of a chassis, but a scale miniature. In fact, if the illustrations were shown as an actually full-sized chassis, they would probably be accepted as such without question.”

Icke’s letter to his friend read: "The scale of the model, which does not represent any known make, is one-tenth.

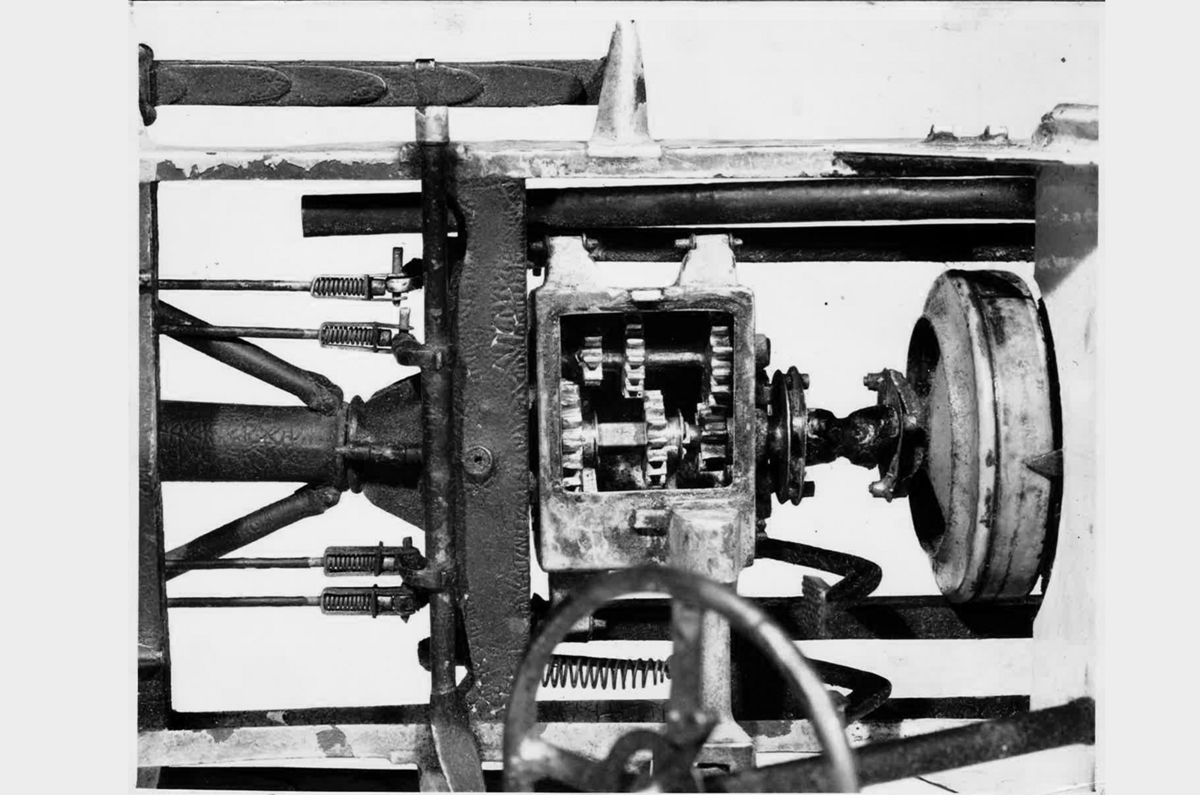

“Every detail is as nearly as possible to scale and, with the exception of the magneto and carburetter, every part works. The material is principally ‘biscuit box’ of every different gauges. Tubular pieces, as well as the cylinders and the pistons, were made by rolling thin tin round a mandrel and then soldering the joints.

“The brass parts were made of the contact strips of old dry batteries from a pocket flash lamp. The gearing was made of an old brass hinge dug up in the garden; this was the first piece of thick metal I had, and previously I had to solder bits of the thin stuff together till I got the thickness I wanted. The teeth of the gear wheels were made by filing.

“Practically all parts had to be built up; so far as I can remember, there are about 1700 separate pieces of metal – that is, they were originally separate. All the principal parts ‘take down', the attachments being eyes and pins, as I had no screws or anything of that kind.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Incredible piece of work

I think most, including myself, would struggle to construct something like this with modern machinery and tools, let along in the PoW camp.

What a brilliant story

What a brilliant story. How on earth did the guy make this while a POW?

I think w're all totally spoiled these days, the old guys knew how to get through. The story of the Colditz glider, told on a TV documentary a few years back was amazing as well. I must admit to shedding a few tears when they rebuilt it and it actually flew.

I love these Throwback Thursday's.