Never before had there been, and in all likelihood never again will there be, an engine like the DFV.

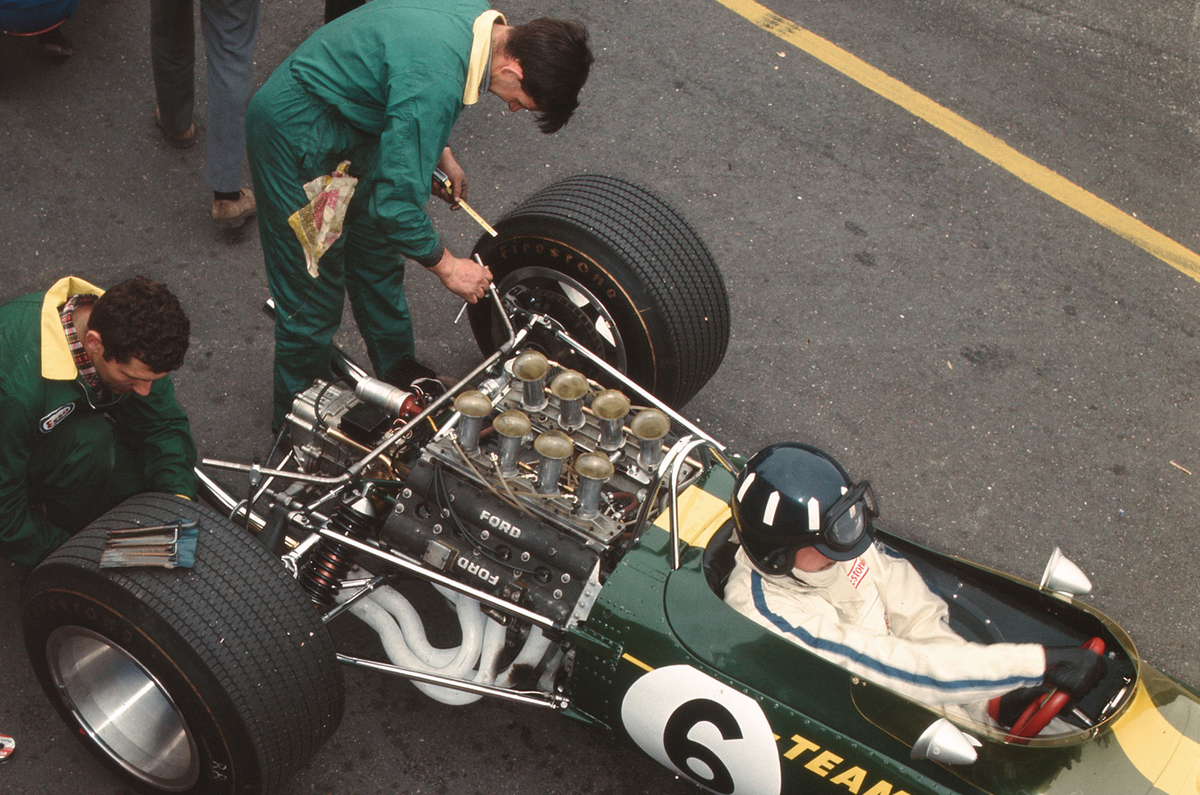

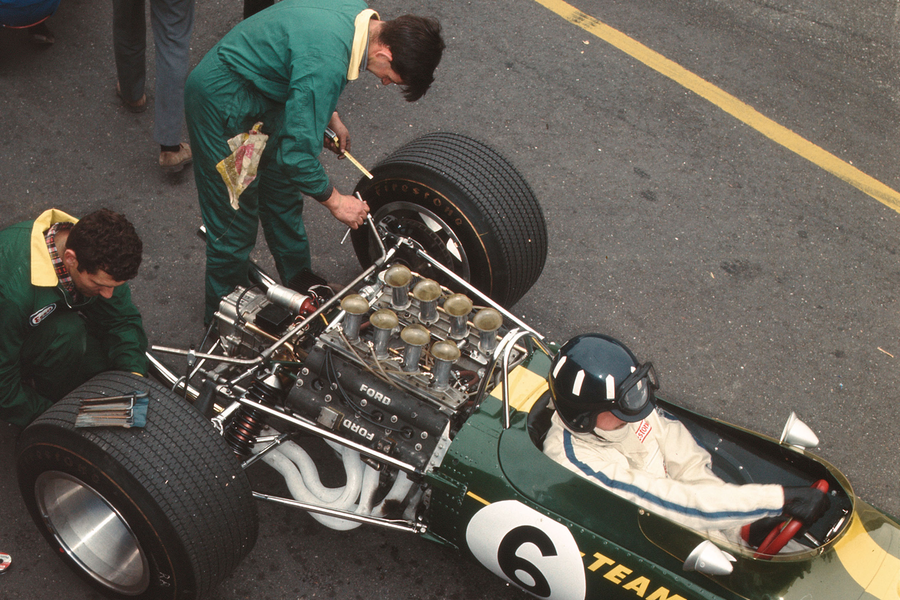

Designed in 1965 by the youthful Cosworth company, its birth was down to Lotus’s Colin Chapman, who both commissioned the project and brought in the crucial backing from Ford.

The DFV made a winning debut at the 1967 Dutch Grand Prix and, continually evolving, took 12 Formula 1 drivers’ championships and 10 constructors’ championships, taking its last win in 1983 and making its last appearance in 1985. At times during the 1970s, nearly the entire grid had the cheap, reliable and competitive DFV bolted in the back.

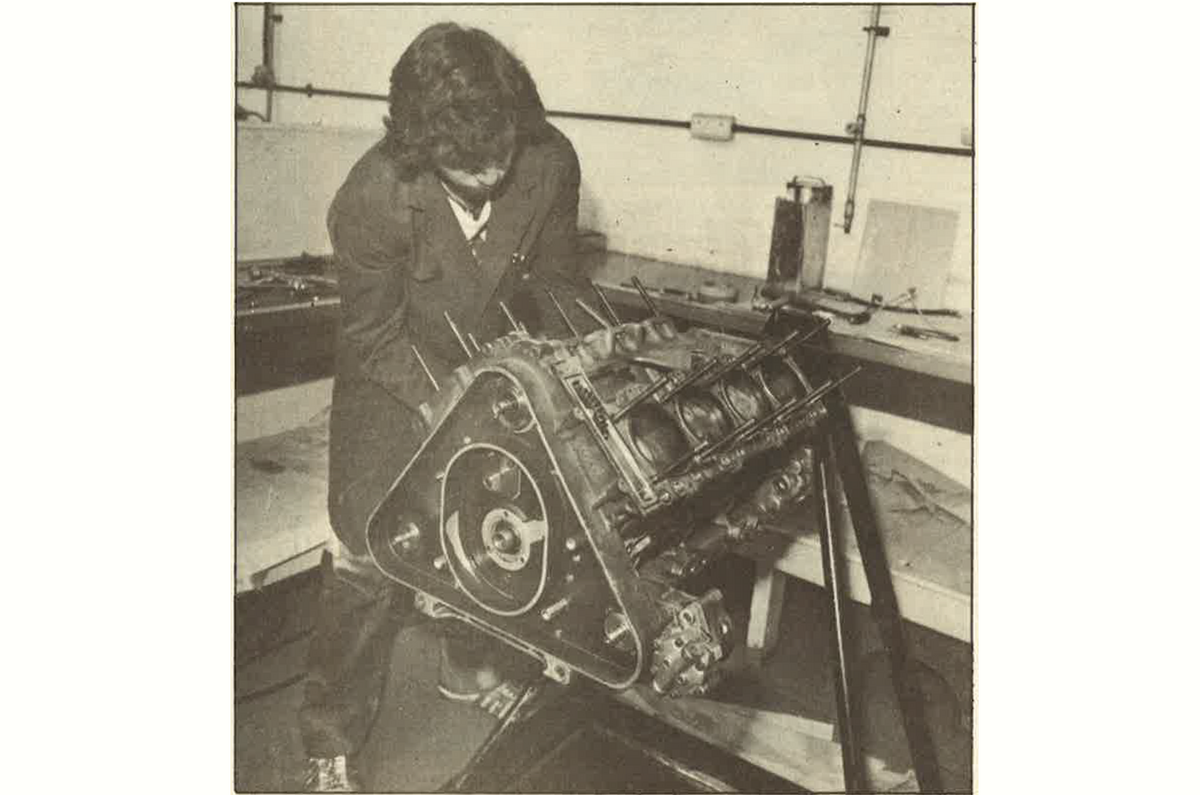

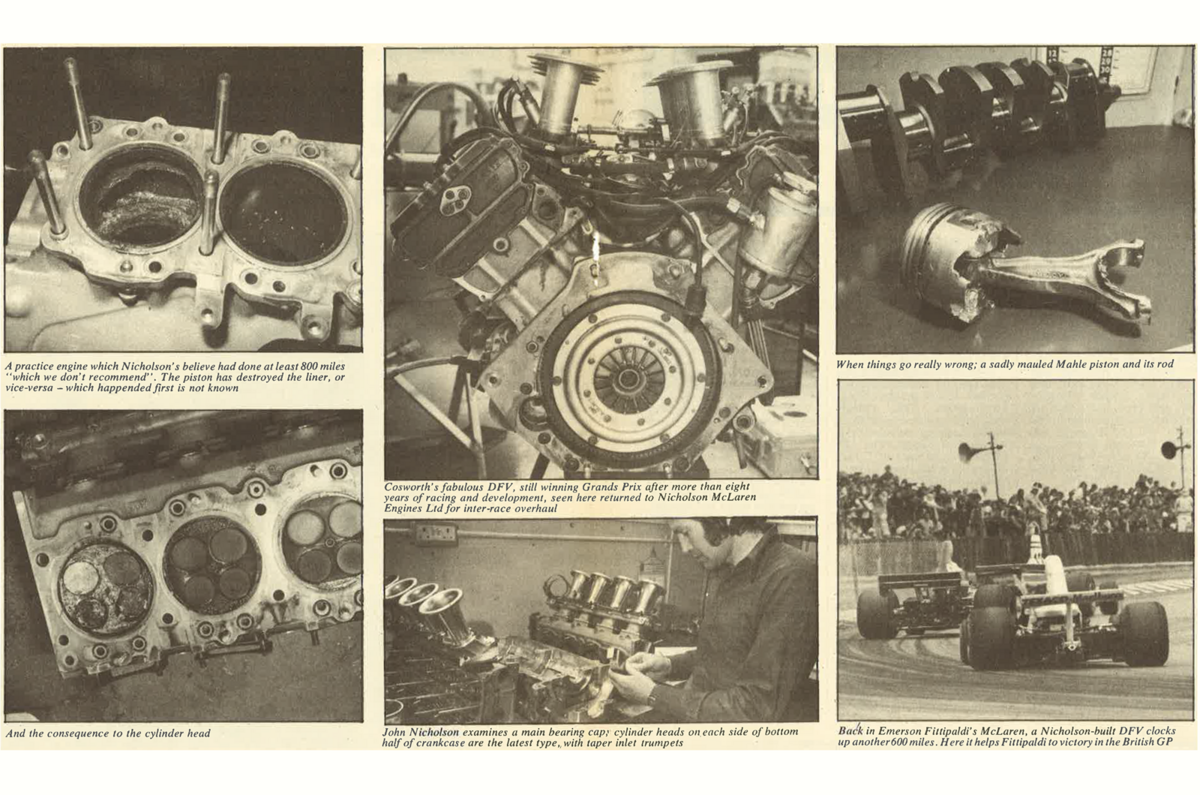

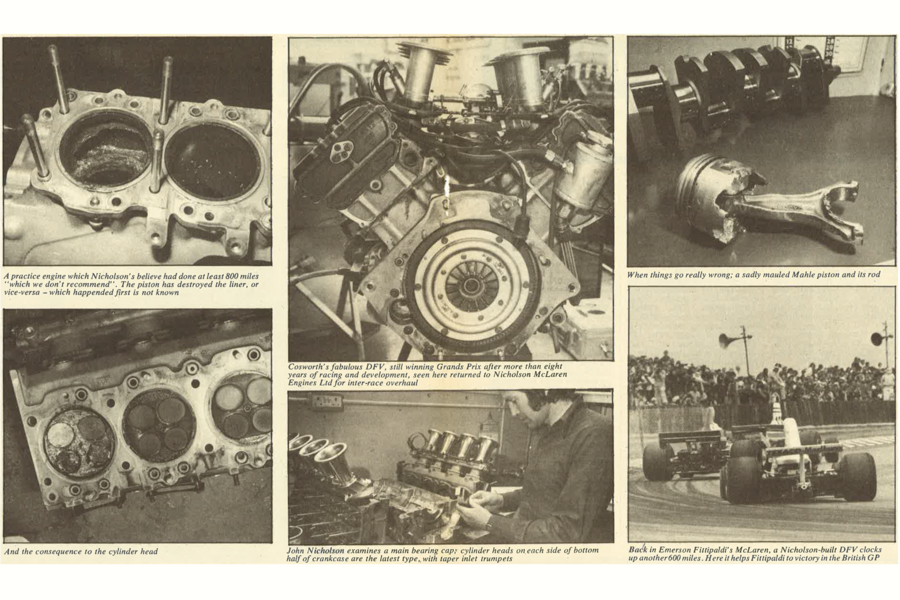

And it's that reliability part we’re looking back on today, because on 2 August 1975, Autocar’s Michael Scarlett paid a visit to see how the DFVs were maintained at Nicholson McLaren Engines Ltd, run by racer-cum-engine preparer John Nicholson.

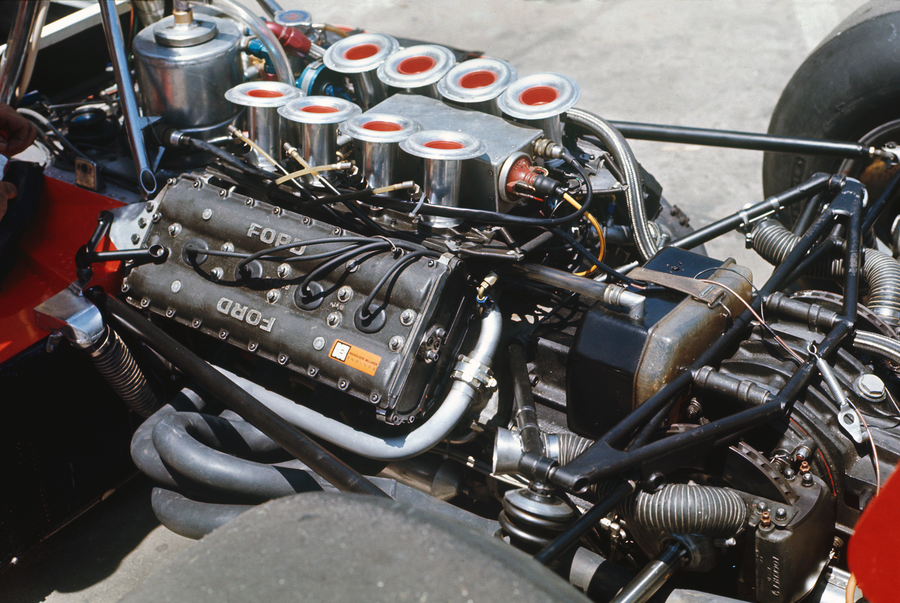

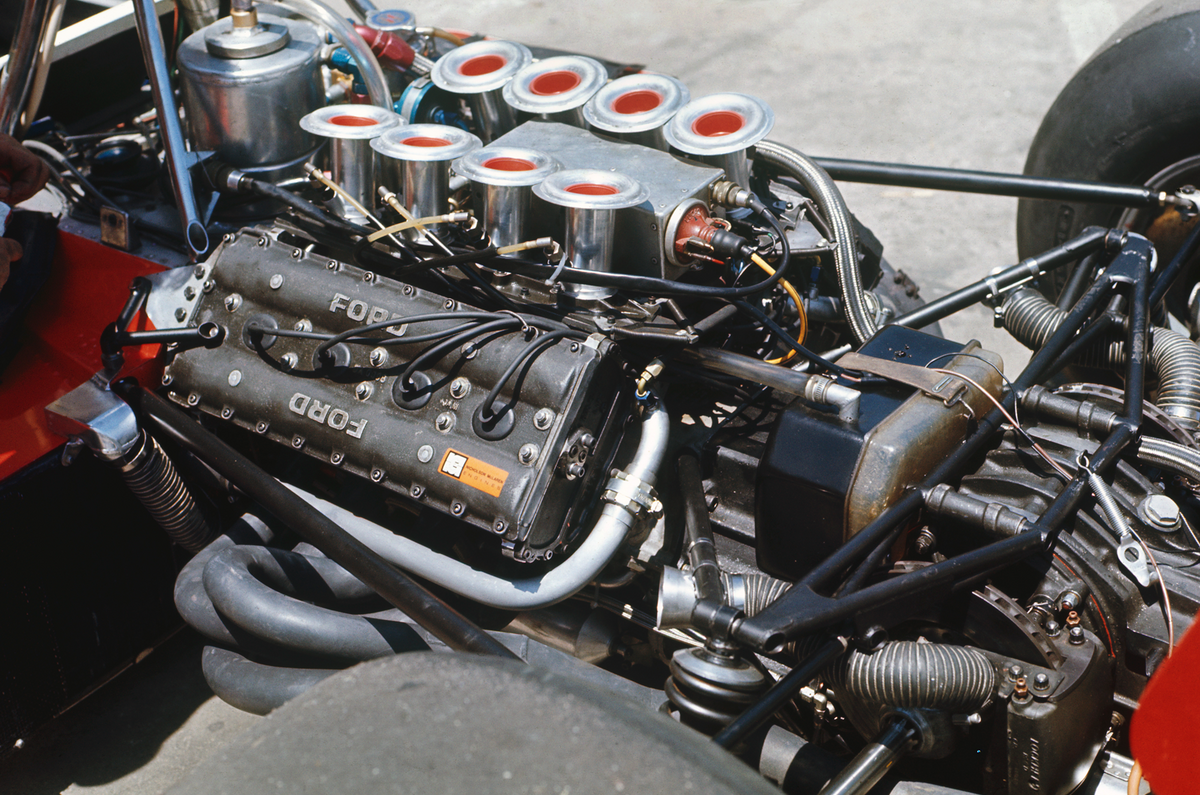

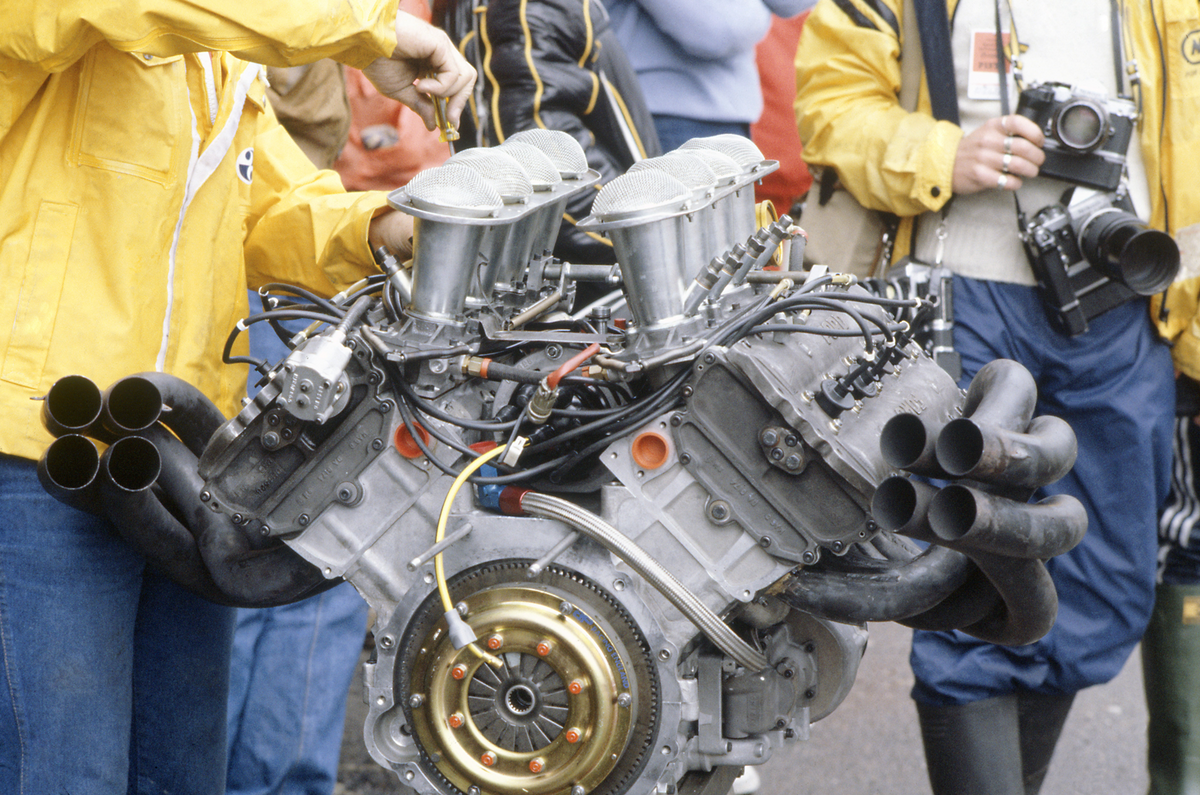

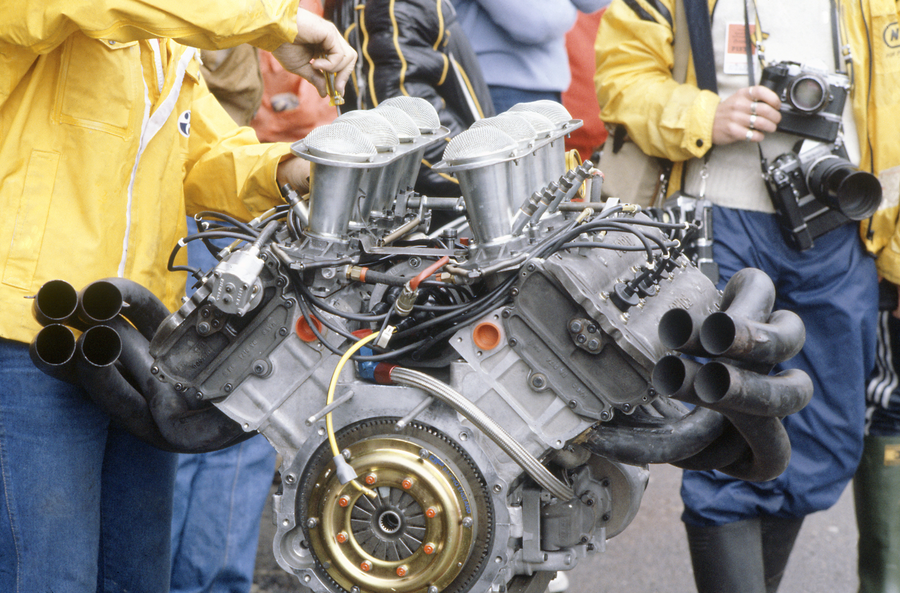

At that time, the DFV was a 3.0-litre, overhead-camshaft, 32-valve lightweight V8 outputting around 475bhp at 10,250rpm.

“One is so blasé about engine speeds... that one forgets how incredible it is that such a device should work so powerfully,” Autocar began.

“The power figures quoted for production engines rarely exceed 66bhp/litre. The specific output of the DFV amount to nearly thrice that, at 158bhp/litre.

“Basically it achieves that by persuading enough fuel-air mixture into cylinders and burning it efficiently enough at the highest possible crankshaft speed. At that moment, from what John told us, with the latest cylinder heads and larger exhaust pipes and recently introduced taper intake trumpets (plain cylindrical for most of their length), it still doesn’t reach peak power at 10,750rpm, proving that it isn’t breathing that restricts but the mechanical limits of the unit.”

Join the debate

Add your comment

Really great article, thanks.

Reading up on the Mirage effort in the 70s recently and how long it took to make a suitably reliable DFV to work for sportscars. Vibration over the longer distances than those seen in F1 was a big problem and many decent finishes were lost through engine failures of one kind or another. Of course they managed to win Le Mans in 1975 with a detuned DFV but much Gulf money had been spent getting there.

The Tyrrell team using the short-stroke DFY development engine in 1983 just before they switched to Renault turbos. They were higher revving and put out about 515bhp, can't imagine the rebuild costs on those.

RE costs

Lovely engine

Oh, and thanks for using the word 'thrice'. I haven't heard that in ages!

Nice to reminisce about the glory days...