Steer-by-wire is one of those technologies that has remained on the fringes for a couple of decades and, except for a couple of production examples and in racing, hasn’t been adopted in the mainstream yet.

It is due in the Toyota bZ4X this year, though, and will be in the Lexus RZ 450e in 2024. Infiniti introduced it in the Q50 almost 10 years ago but the ‘redundancy’ was mechanical, with a steering column remaining in place, just in case.

True steer-by-wire has no mechanical connection between the steering wheel and steering rack, just an electronic link, and that’s what the Toyota and Lexus One Motion Grip system will have.

Although it may seem like a dodgy idea, there are many benefits, both for manufacturers and drivers. Steer-by-wire comes under the broader category of drive-by-wire elements, such as electronic throttle control, which have been in production for years. One advantage for manufacturers of by-wire systems is the potential to produce a ‘dry’ chassis, with no hydraulic fluid involved.

With steering, that was solved by the introduction of electric power steering, but braking systems are still hydraulic. The major parts suppliers have been working on fully electric braking systems for years.

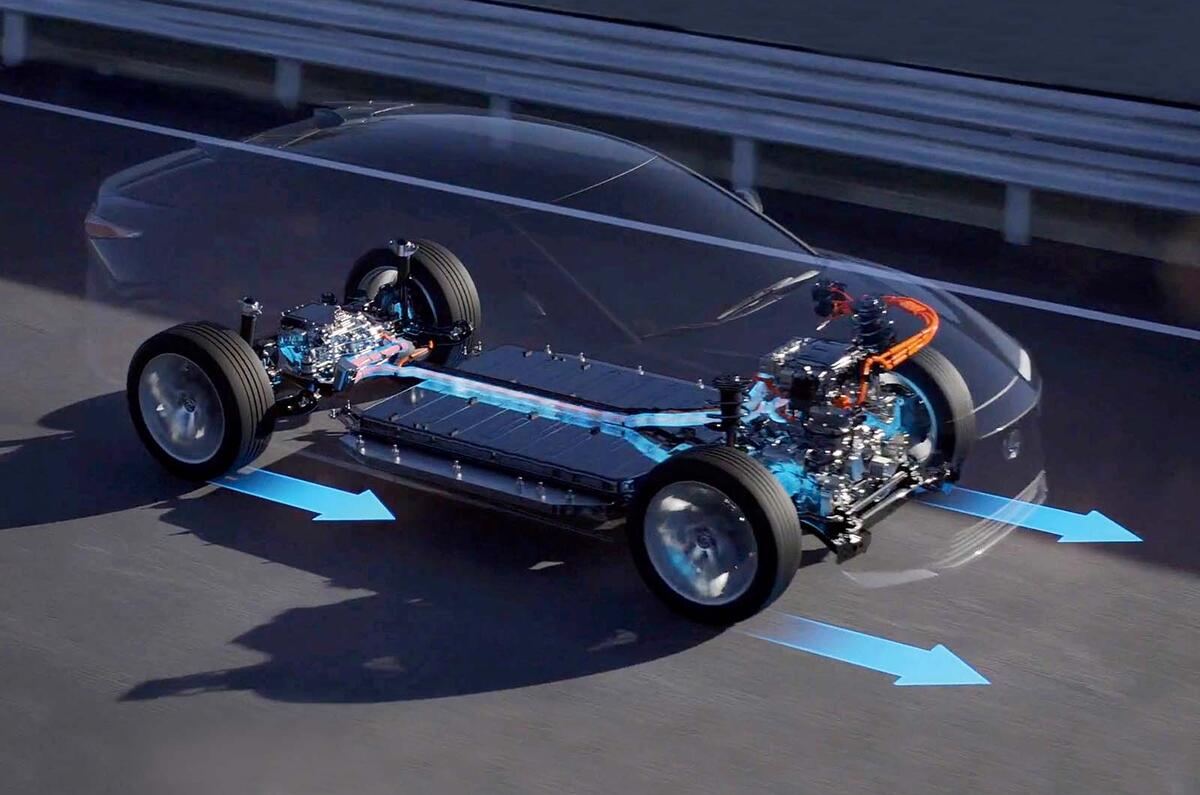

The idea is for each suspension corner of the car to be pre-assembled and bolted on to the car on a production line and literally plugged in, doing away with messy hydraulic fluid and all that entails.

A full steer-by-wire system is even more mechanically simple. The steering wheel directly works a control unit like a gaming machine and motors on the steering rack actually move the wheels.

Linking the two, a computer brain takes the signals from the driver’s steering input and relays them to the steering rack. The caveat is that the computer decides what the wheels will do and not necessarily the driver, but the benefit is that steering lock can be almost infinitely variable, reducing turns in the case of the Toyota and Lexus to a mere 150deg in either direction at parking speeds.

The ratio is reduced as the car gathers speed, slowing the response right down at motorway speeds to avoid the car becoming twitchy.

That last aspect is true of more conventional variable-ratio steering, but steer-by-wire also opens up the possibilities for semi-autonomous safety systems like accident avoidance, where a car can literally steer out of trouble if the driver isn’t quick enough.

It also means that for less able drivers, cars could be steered by a mini wheel or a joystick. Like some aeroplanes, which have relied on fly-by-wire systems for years in both civilian and military aviation, the systems are fully redundant, which means that if any critical hardware or software parts fail, there’s a back-up ready to take over.

Ultimately, there’s the ‘A’ word: full steer-by-wire is a must for autonomous vehicles, which is why over the next few years we are likely to see more examples of it appearing.

Join the debate

Add your comment

How about “a continuously variable steering ratio between variable limits”?

A pretty impressive bit of kit.

Two major problems with this (probably lots more):

1. This, and electric power steering, are the death of driving enjoyment.

2. If a car equipped with this has an accident or loses power, how is anybody going to be able to steer it to move it off the road?