The Saurus, Nissan’s lightweight mid-engined sports car that fascinated the world when it appeared as a prototype at the 1987 Tokyo motor show, is alive and well and racing in Japan.

Under the lights at the Harumi Fairground 16 months ago, the Saurus looked like a good idea that wouldn’t come to anything – a kind of Japanese Caterham Seven. But would Nissan build it? At the time it appeared unlikely.

After the show the Saurus seemed to sink without trace, although periodically it did the rounds of local dealer showrooms in Japan. It was a prototype, said Nissan and, no, you couldn’t really learn anything from driving it.

Then, in the latter half of 1988, came the reprieve. The Saurus was resurrected in faster, more developed form, but for the track, not the road, to form the basis of a new Japanese one-make race series called the Saurus Cup. And in January came an invitation to Tsukuba circuit to track test the reborn Saurus.

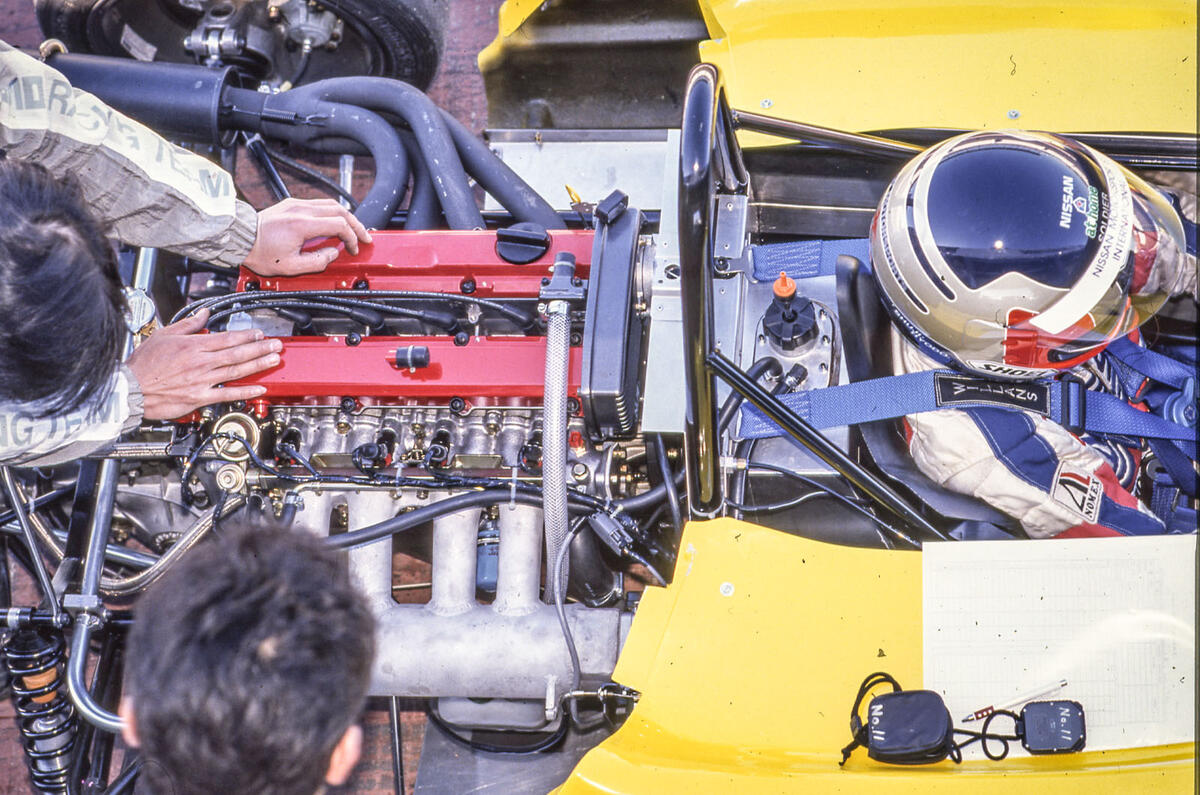

Nismo, Nissan’s competition wing, had brought along three cars – two in the original silver and blue colours of the show car and a third painted bright yellow. The first two were ‘training’ cars for learners, while the yellow car was the full-house racer, a significantly different machine from the original prototype.

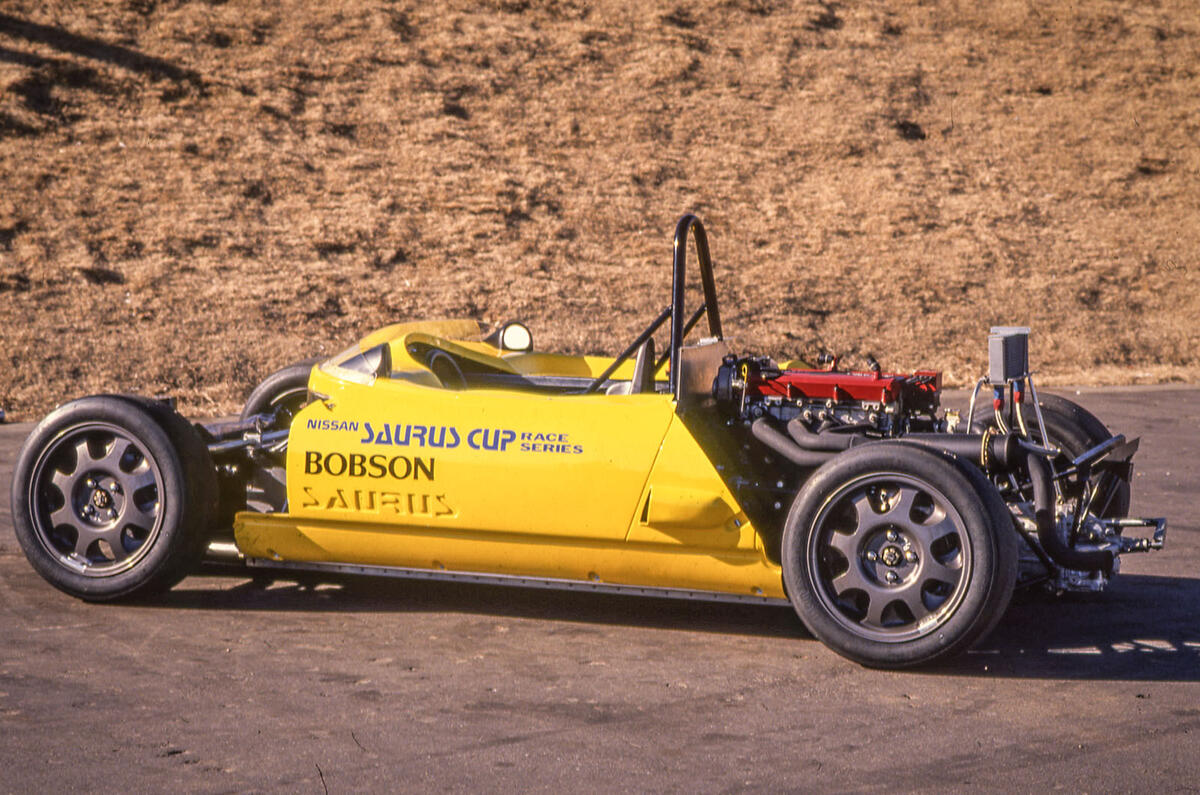

The shape is much the same – a slim body, gently curved all the way round, with big flared wheelarches sprouting from each corner. As before, there are no doors nor roof and a tiny windscreen that looks as if it is just for show.

The tiny headlights of the show car have been replaced by a massive full-width spoiler to provide downforce. Another notable absentee is the passenger’s seat: Saurus is now a single-seater and, with a length of 3345mm, almost exactly the size of a Caterham Seven.

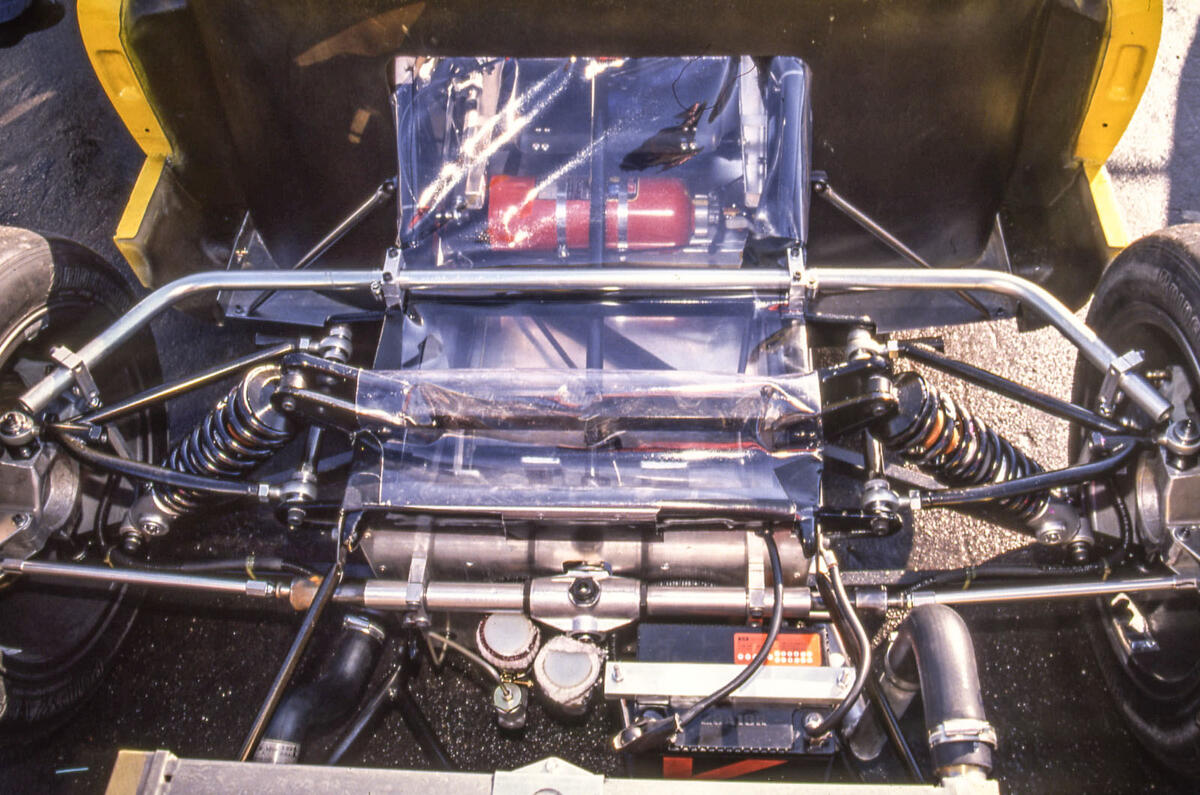

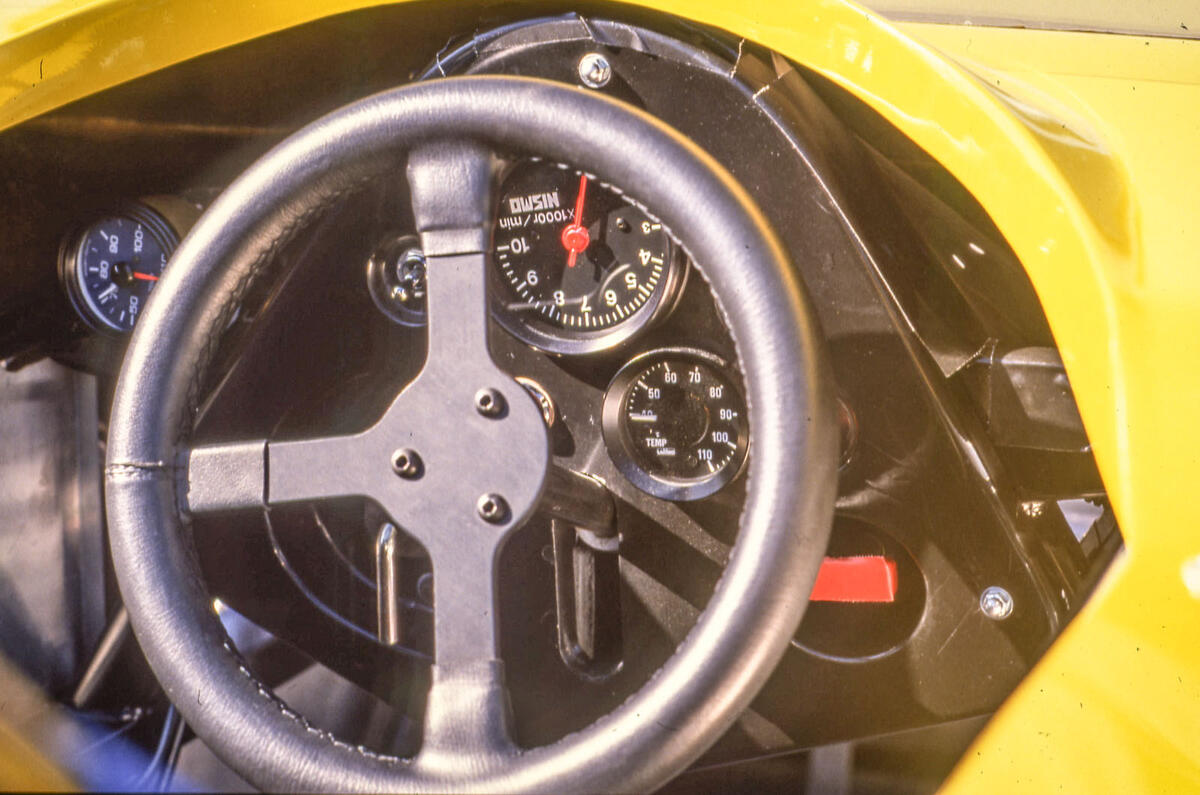

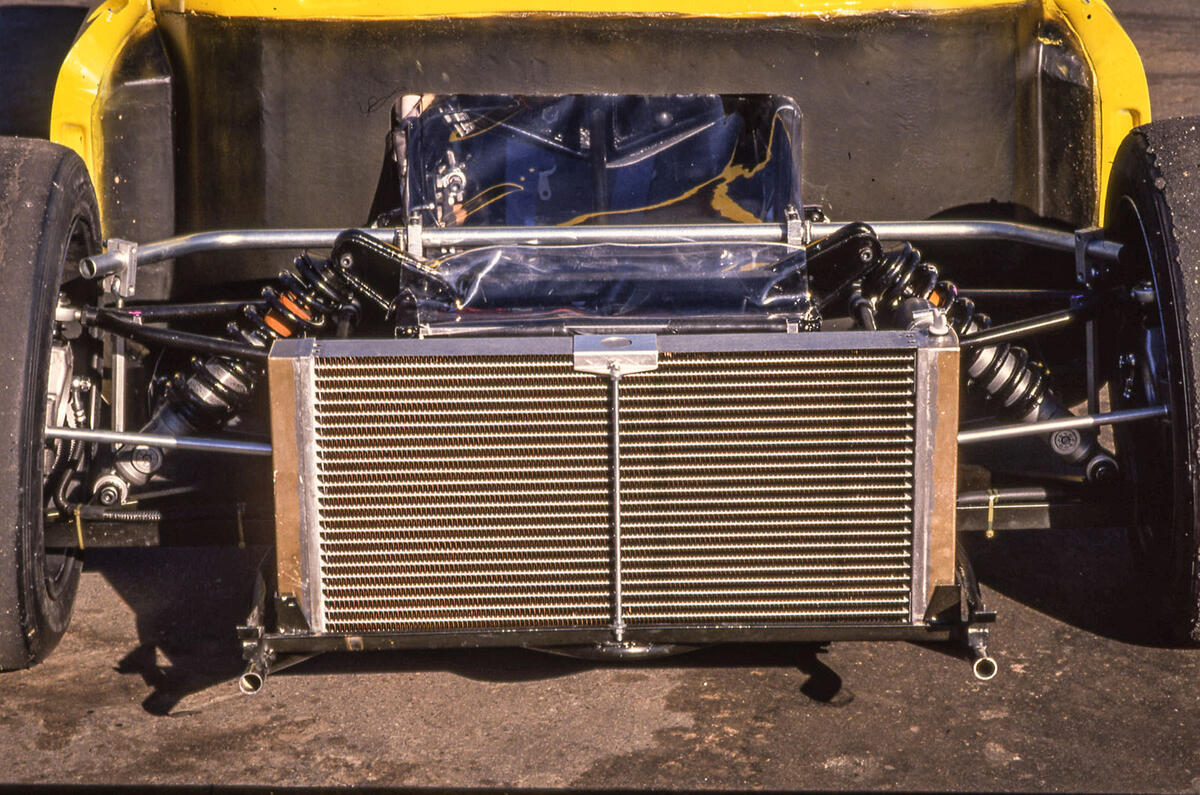

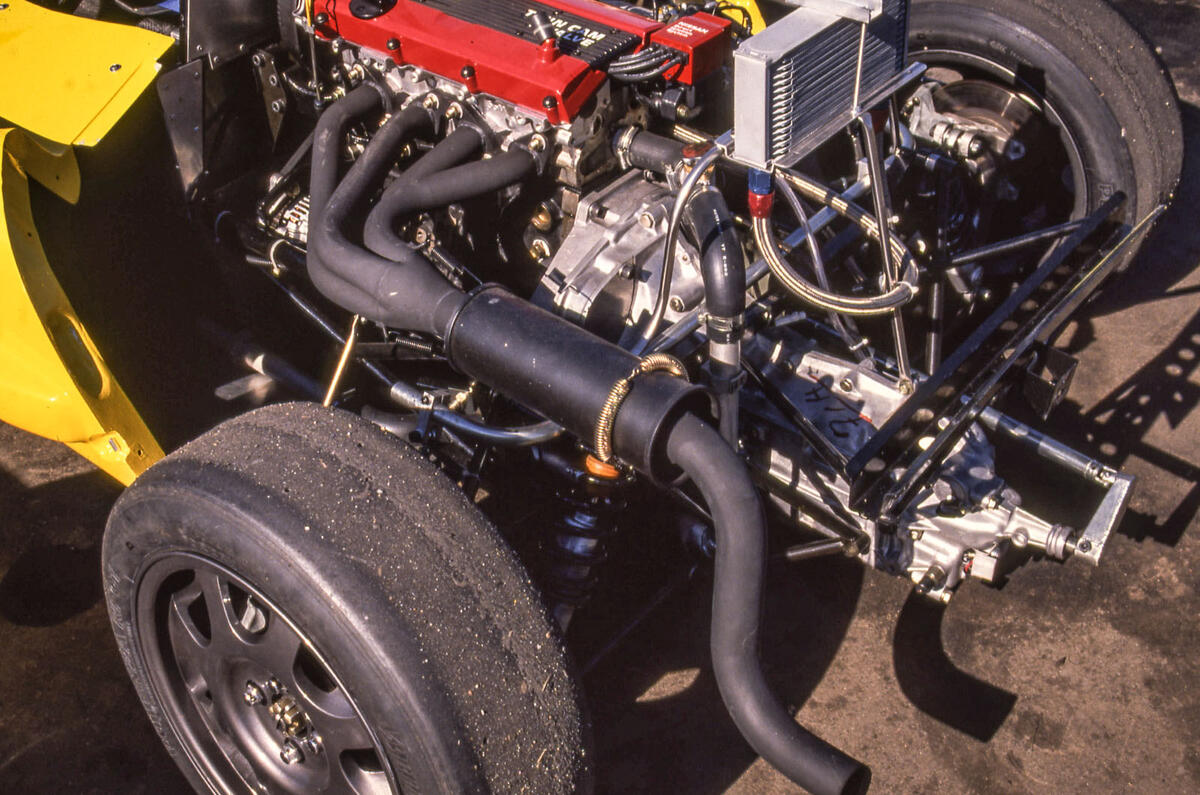

Standing just 1090mm high (including rollbar), it’s a low-slung machine, with a tubular spaceframe chassis. There’s a pressed steel tub for the driver and subframes for both front and rear suspension. The glass-fibre body has one-piece front and rear panels, which lift off.

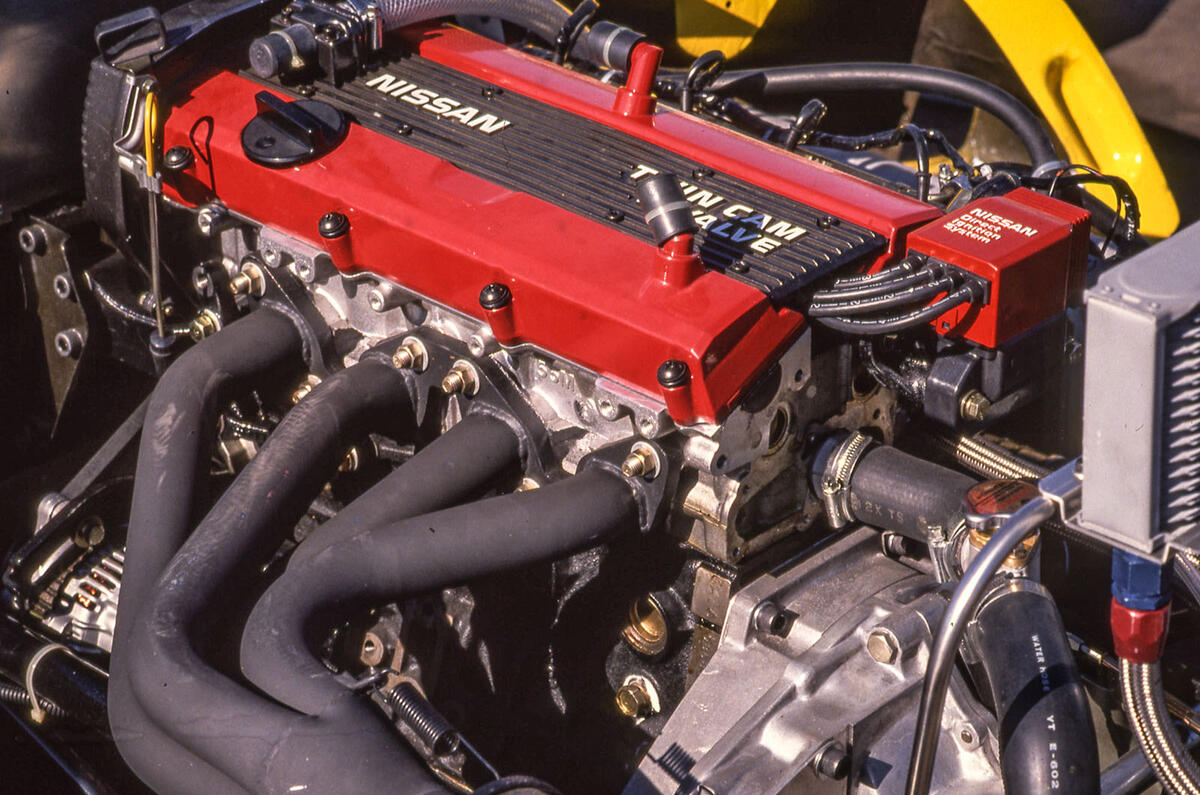

Gone also is the Saurus’s original one-litre supercharged and turbocharged engine (only to reappear in the latest and hottest Japanese Micra). In its place, Nismo is using a standard Bluebird 1.8-litre engine for training purposes and a Sunny 1.8-litre for racing.

The engines, which sit longways behind the driver, produce 125bhp and 135bhp respectively. Both have iron blocks and twin-cam, 16-valve heads. There’s a computerised electronic injection but no turbo. For the racer, no modification is allowed, save blueprinting and the choice of a new exhaust manifold. Maximum power arrives at 6800rpm, with a 7500rpm rev limit.

The five-speed gearbox is derived from the Subaru Leone 1.6. No official reason has been given for this curious choice, but the gearing has been radically altered for a very close ratio ’box.

The suspension is different from the show car too. The training Saurus uses complex-looking five-link geometry front and rear, with inboard coil-spring/damper units mounted ahead of the front pedal box. That was all right for low drag, says Takashi Mihashi, manager of Nismo’s engineering department, but proved difficult to set up accurately. The latest development is simple double wishbones all round, outboard dampers and massive adjustable anti-roll bars.

Add your comment