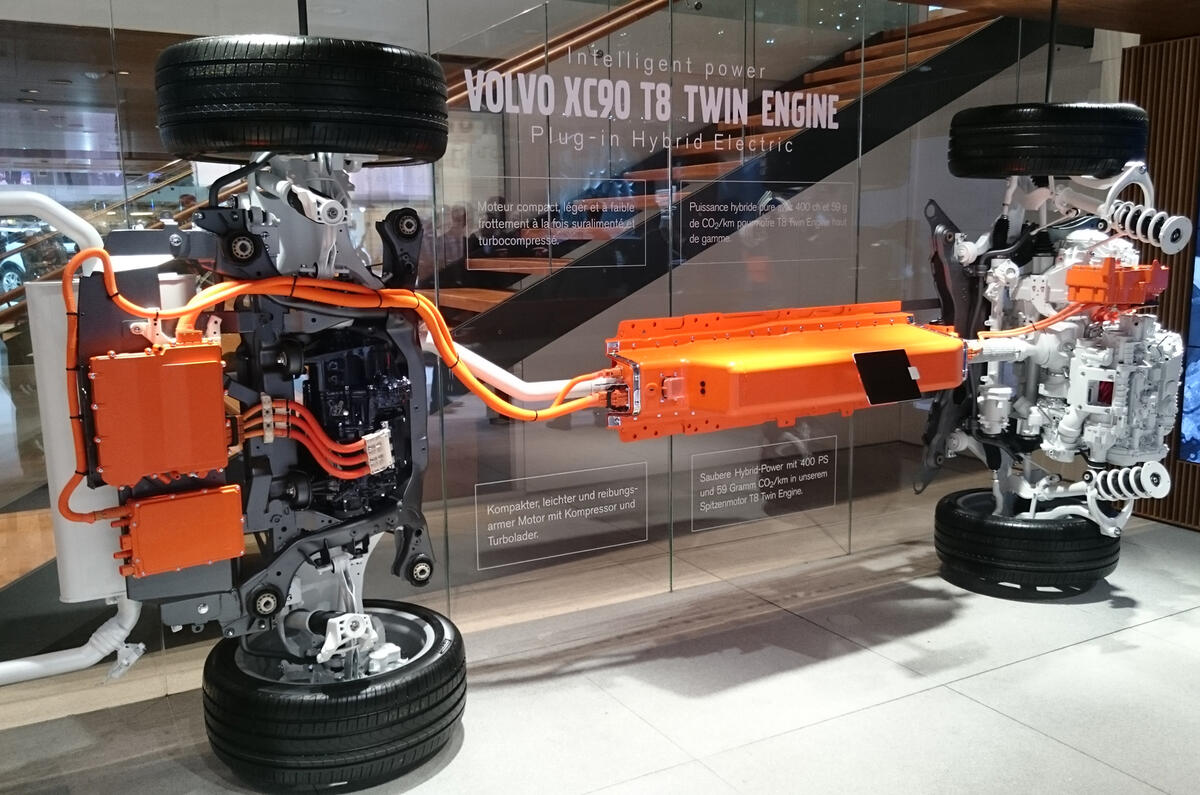

If you appreciate the sheer genius of the engineering that goes into today’s top-end cars, I recommend seeking out this extraordinary Volvo exhibit at the Geneva show.

This is the drivetrain of the range-topping XC90, and it is made up of a feast of the most expensive technology available for series production. At the front there is Volvo’s new four-pot 2.0-litre petrol engine, which is fitted with both a supercharger and a turbocharger.

This powerhouse is linked up to an eight-speed automatic transmission, but sandwiched between them is an electric motor/generator. At the rear, the back axle is powered by a second electric motor.

Inside the XC90’s centre tunnel is a 9.2kWh battery pack. This is painted orange, as are the various electronic hybrid control systems and the electric cables. On top of that expensive and complex kit, the XC90 also has properly sophisticated double wishbone front and independent rear suspension set-up.

I can’t imagine the cost of building the XC90 T8. Aside from the huge research and development bill, the factory cost of building this extraordinary machine must be formidable.

And as much as I admire it, I can’t help wondering whether the car industry – led by California’s highly influential market tastes and regulations – has been sent up a blind alley.

The reason behind all this tech is so Volvo can produce a car with the performance of V8 (hence the T8 designation) but with much lower CO2 emissions, all in order to appease both California's car buyers and its legislators . California also leads the way in reducing the levels of exhaust pipe pollutants.

Is a complex mix of internal combustion engine, electric motors and battery packs the best way to achieve these aims? Perhaps not. For many years in the US, Honda’s modest Civic CNG has been winning ‘green car’ awards.

In terms of pollutants, natural gas is a clean-burning fuel; in terms of CO2 emissions, it’s about 30% better than petrol. It was also noted that Civic used ‘locally sourced’ fuel. And neither does it use lots of rare-earth metals in its construction or rely on chemical-heavy battery packs.

Sure, it can’t be plugged into the electricity network and gain 30-50 miles of battery-powered progress. But how is that mains electricity generated?

In the UK in 2012, around 42% of electricity was generated by coal, 28% by gas and 20% by nuclear. Renewables, in more recent years, is peaking about about 15% of (intermittent) supply.

In 2013, the US power split was 39% coal, 27% natural gas, 19% nuclear and 7% hydro. So around 56% of supply is fossil fuel-derived.

In the future, gas, which is clean burning and in good supply globally, will increasingly replace coal as the backbone of electricity generation. So I look at the XC90 T8's engineering magnificence and wonder whether it should have a petrol engine optimised to run on gas and that giant battery pack replaced by a gas tank.

Join the debate

Add your comment

I often wonder what the

Lightening Duck

Ecotricity puts about £160 in from each bill on average, but does make you wonder if you sign up for someone who does zero carbon but doesn't invest if you are actually reducing any carbon at all.

Lightening Duck

Phil R