Fifty years ago today, just before 9.00am, Britain lost a unique individual, a man whose patriotism, courage, superstition, determination and insecurities made him one of the most complex, remarkable characters ever to attempt to do what no man had done before. His name was Donald Campbell.

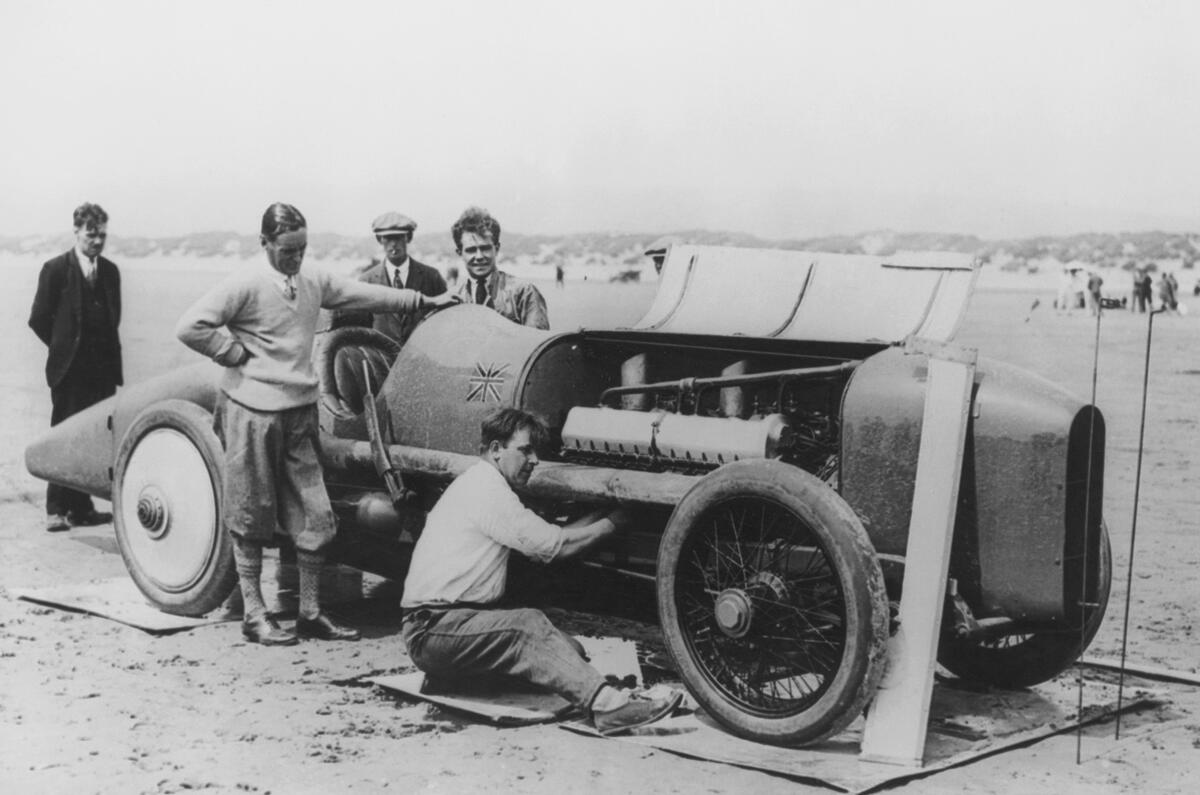

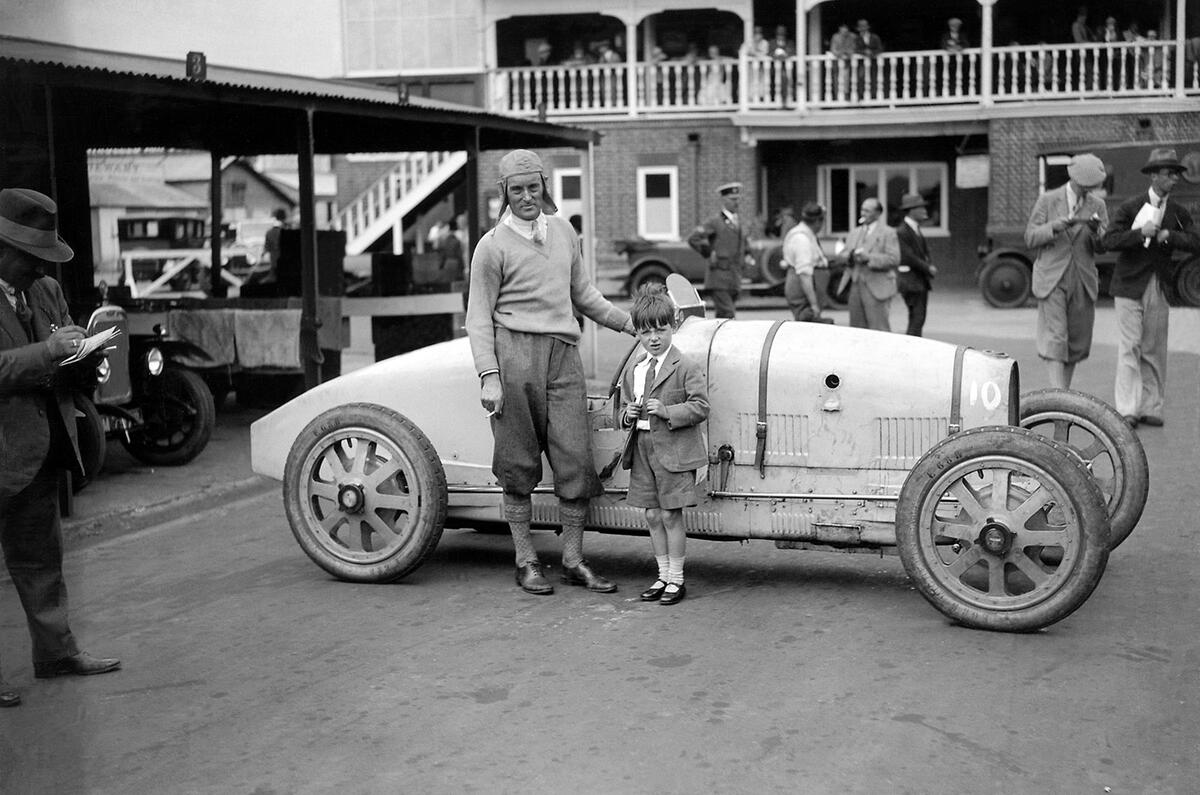

He was, of course, the son of Sir Malcolm Campbell, the serial Land Speed Record breaker of the 1920s and 1930s and it is said Donald went to his watery grave on Lake Coniston trying to live up to memory of the Old Man. But Leo Villa, the long-serving engineer to both generations of Campbell and the man who perhaps understood him best, saw it another way. As soon as the young Donald started toying with the idea of record-breaking, Villa told him: ‘Once you start this, there’s no end to it. When it’s in your blood, it’ll be there for good.’

I hope there’s a magazine called Autoboat or something that is marking this sad anniversary too, for whatever Donald Campbell achieved on land, it pales compared to his achievements on water. His father had set a world water speed record in 1939 at 142mph and Donald’s first outings were in the same boat, Bluebird K4, which he eventually coaxed up to 170mph before wrecking it. But by then the record was far beyond the reach of K4, so he designed an all new jet-powered hydroplane, Bluebird K7 and went to work.

Between 1955 and 1964, K7 set seven water speed records, raising unopposed the record by almost 100mph from 178mph to 276mph. In the 53 years since, the mark has been raised just 43mph more. No one broke the record more times, no one raised it by more than half as much as Campbell. Though others achieved more on land, in the realm of the water speed record, Donald Campbell was, is and will almost certainly remain the undisputed, unapproached king.

But this is Autocar and the clue is in the title. And the truth is Donald Campbell never achieved his goals on land, and while undisputedly though briefly the holder of the Land Speed Record, he was never the fastest man on earth.

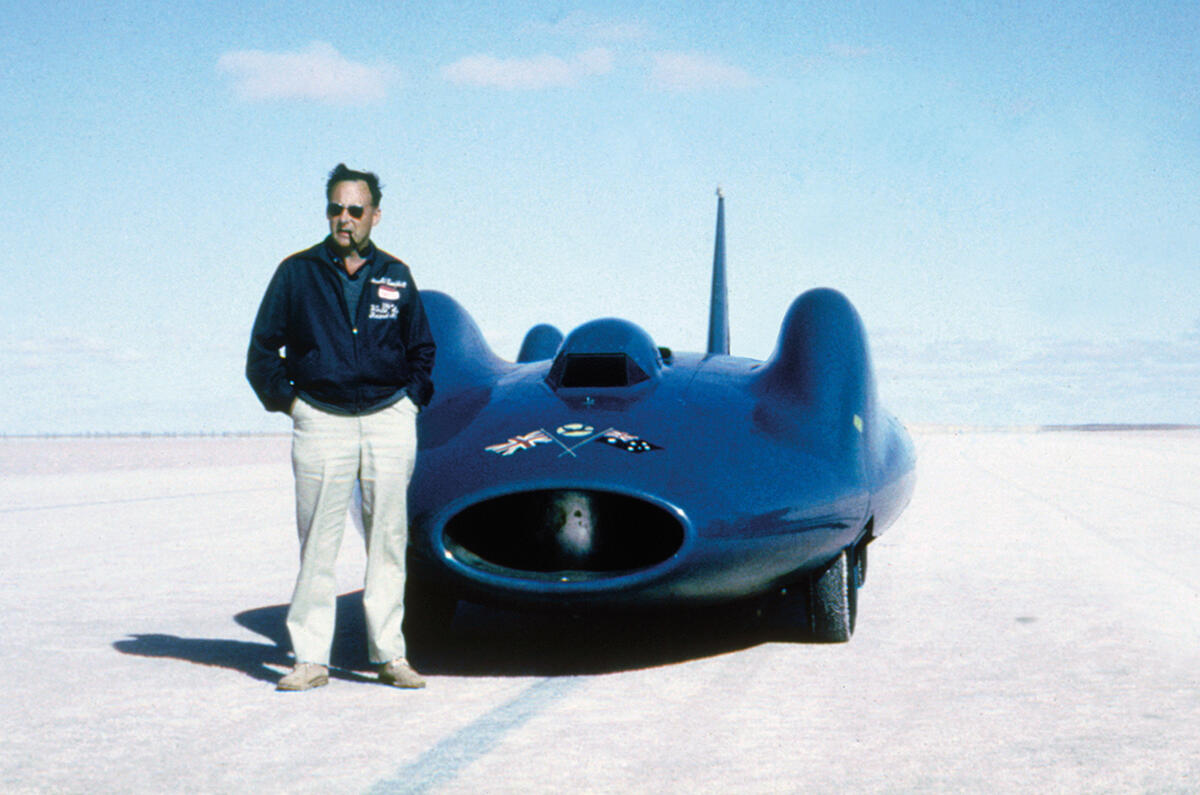

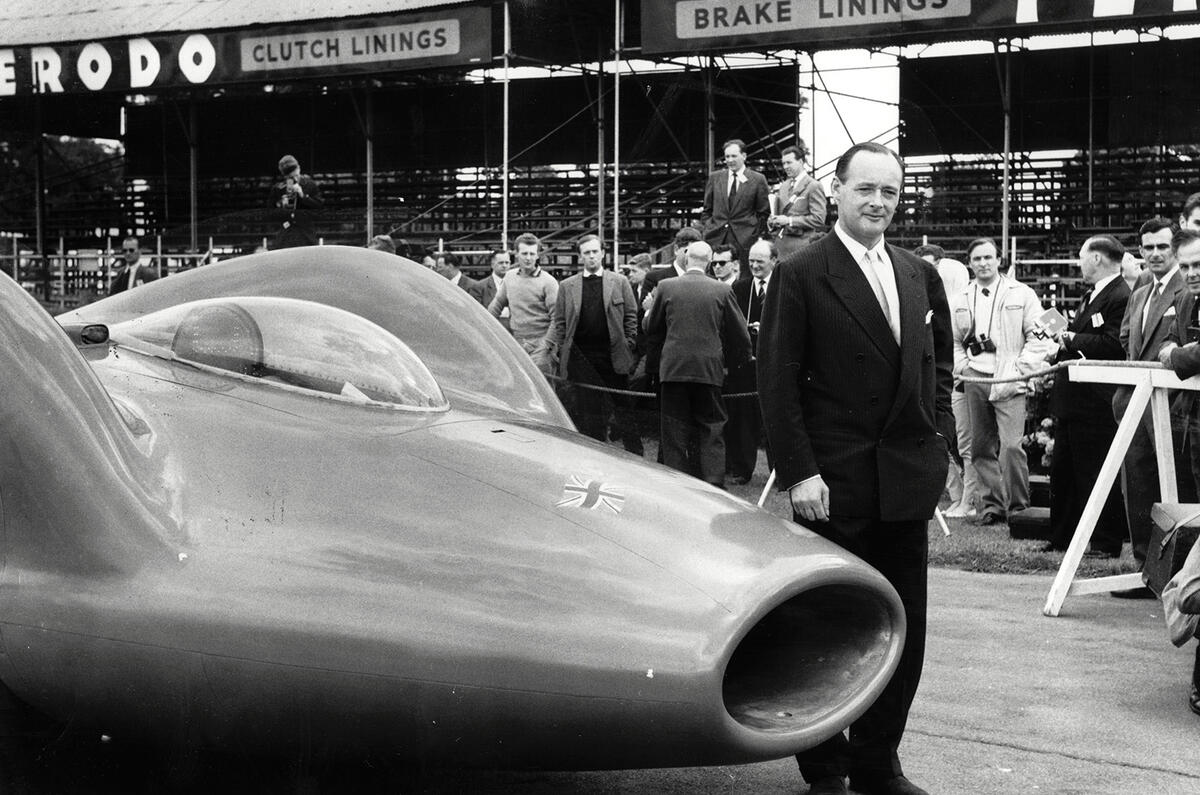

I’ll explain. Campbell had already broken the Water Speed Record many times before he turned his attention to land and believed the massive, turbine powered Bluebird-Proteus CN7 he’d had designed would enable him not only to beat the 394mph mark set by John Cobb in 1947, but smash it to smithereens. Indeed it was designed to do 500mph. But when it was ready in 1960, Campbell chose to drive it at Bonneville, the site of his father’s last Land Speed Record, and rolled it into a ball at over 350mph. Luck and the car’s inherent strength allowed him to escape alive, but suffering severe concussion and a fractured skull. It was four years before the car could make its next attempt, at Lake Eyre in Australia.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Respect

For anyone who respects the man and his achievements I strongly recommend you get the DVD of 'Across the Lake', made for TV in 1988 and starring Anthony Hopkins (who, as always, was brilliant, playing DC). It will bring a tear to your eye.

Donald Campbell

I had the very great pleasure to meet him at a Motor Show held on the Pantiles in my hometown of Tunbridge Wells the year before he died (1966). I still have his signature in my Autograph book....in fact the only signature in my Autograph book as at the time I felt I had achieved my ultimate dream in speaking to the great man.

Some say he wasn't very approachable, but I can only speak as I find, and he spent more than 15 minutes with me....showing me around a new Rolls-Royce (Shadow) in some detail before signing my book. He was very kind to me.

It made my year at the time (much to the amusement of my parents), but sadness was to follow.

After Clark's death I vowed to forget the concept of 'having a hero'.....losing two in short order was too much to bare.