With their thrilling sci-fi aesthetics, spaceplanes are an attractive alternative to rockets. They are attractive in practical ways, too.

Unlike traditional rockets, spaceplanes are reusable, flying multiple times and potentially slashing launch costs. Some can operate from normal runways, offering far more flexibility, and their efficient engines lower their environmental impact; others are launched atop rockets or ‘motherships’, reducing the fuel they need to carry and burn. Promising to be easier, greener — and far cooler — why have most spaceplane projects never managed to get off the ground? In the very rare cases that they do, why does the project not ‘take off’? Let’s find out.

10: HOTOL

A serious interest in space travel began in the UK before the war, led by the British Interplanetary Society, whose members included Arthur C. Clarke. Postwar, Britain studied captured German V-2 rockets and proposed crewed suborbital flights, such as Megaroc. Official programmes began in 1952, emphasising military and scientific research, while Skylark rockets, launched from Woomera from 1957, advanced uncrewed space exploration.

In 1971, the Prospero satellite was successfully launched by the Black Arrow rocket. But the government had already cancelled the programme, ending Britain’s independent spaceflight efforts and closing its national rocket era by the early 1970s. British Aerospace, a new conglomerate founded in 1977, had great ambition and wouldn’t give up on Britain’s return to space.

10: HOTOL

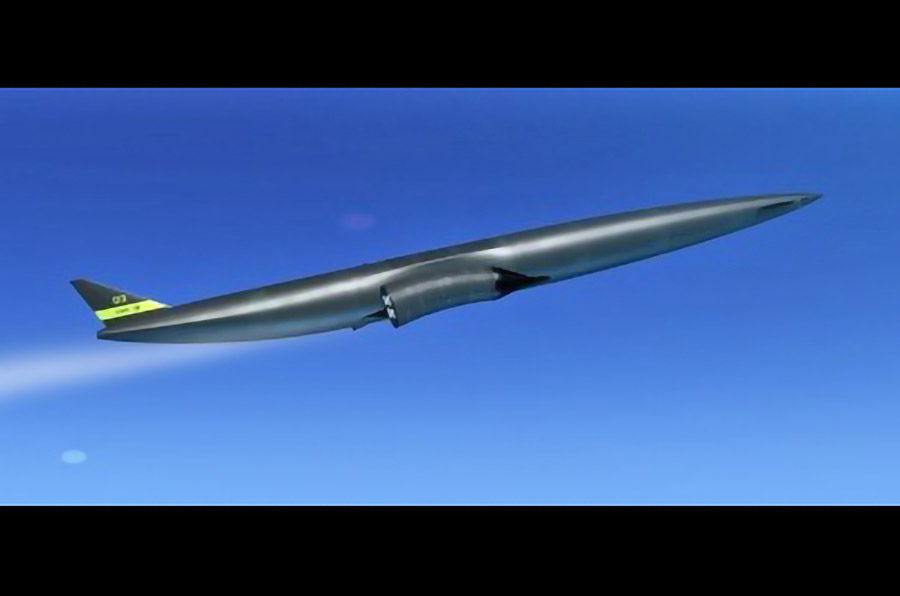

In collaboration with Rolls-Royce, British Aerospace proposed HOTOL. Concept studies began in the early 1980s; the formal HOTOL project started in 1986. The aim was to create a reusable, single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane powered by an innovative RB545 “Swallow” engine. After reaching orbit, HOTOL would glide back through Earth’s atmosphere to land conventionally.

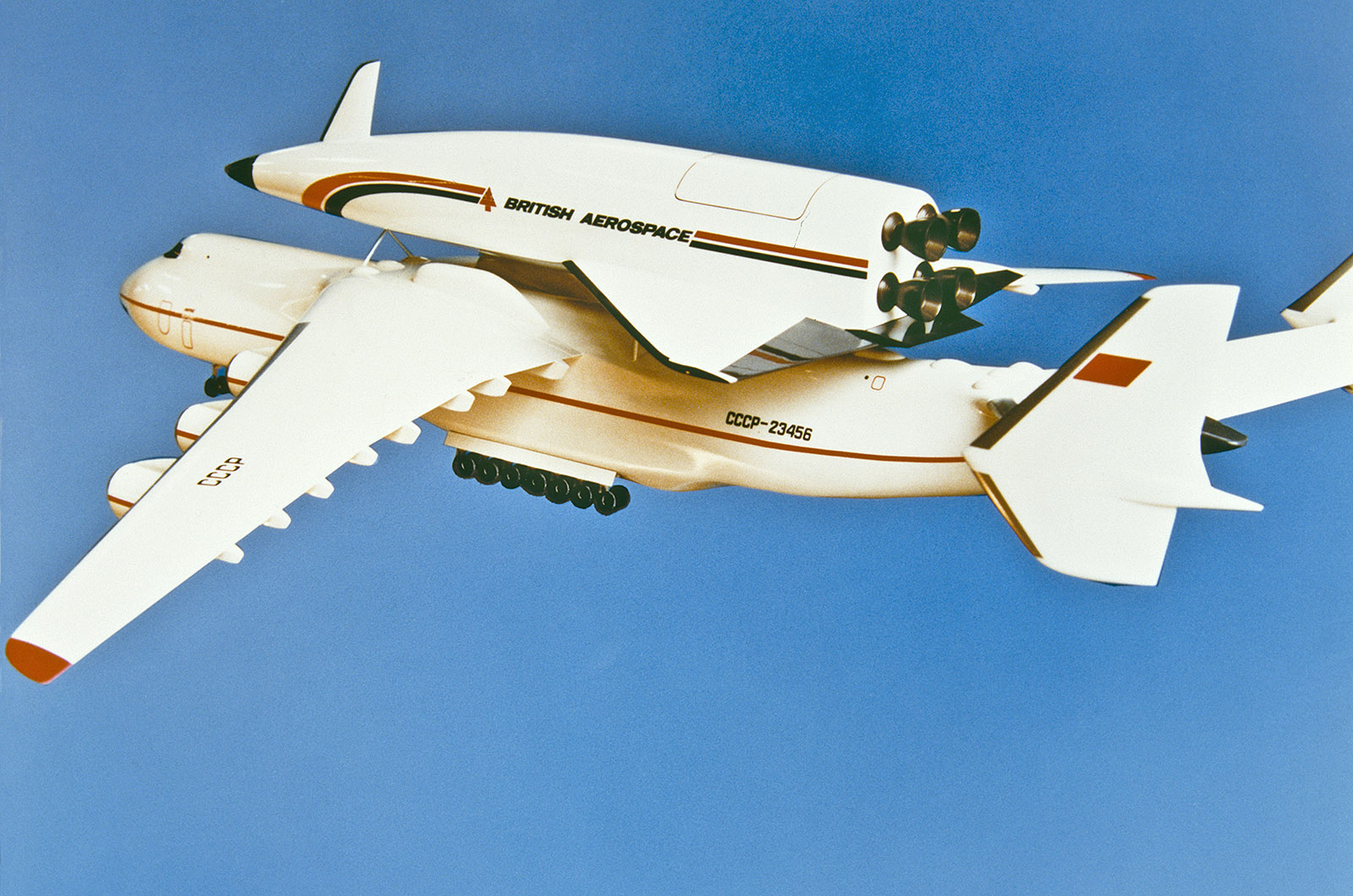

The Rolls-Royce RB545 “Swallow” engine was a groundbreaking hybrid air-breathing rocket, decades ahead of its time. Using atmospheric air at low altitudes and switching to liquid oxygen in space, it promised seamless, single-stage, reusable spaceflight — a revolutionary leap in propulsion design unmatched by any operational technology of its era. The programme was cancelled in the late 1980s due to funding issues and technical challenges. A later proposal envisioned launch from the top of the Antonov An-225; it also never materialised.

9: MiG-105

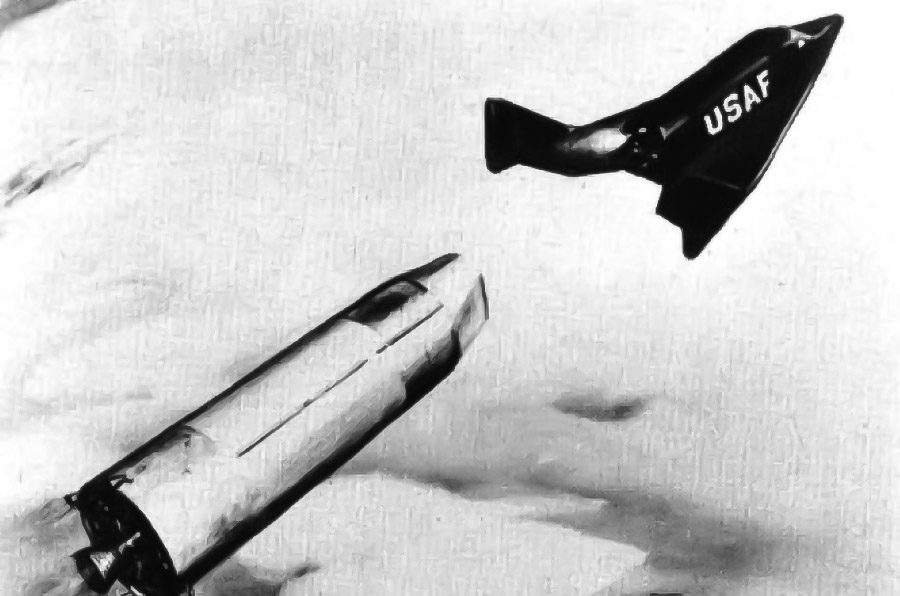

With envisioned roles including the destruction of NATO satellites, this Soviet spaceplane project was thrillingly James Bond-esque; Even more excitingly, at one point, it was proposed that the craft be launched from the back of a Mach 6 Tupolev carrier aircraft. After separation at high altitude, its own detachable rocket booster would have ignited, propelling the small spaceplane directly into a sub-orbital altitude.

The MiG-105 emerged from the Soviet Spiral programme, aiming to create a small orbital spaceplane that could return to Earth like a glider. Its compact, wedge-shaped body earned it the nickname ‘Лапоть’ (Lapot) or ‘Little Shoe.’

9: MiG-105

The MiG-105 was used to test landing techniques and low-speed flight characteristics. It took off under its own power from an old airstrip near Moscow in 1976 for its first subsonic free flight. It conducted eight subsonic flight tests between 1976 and 1978; some were air-launched from a Tu-95K bomber.

Add your comment