Before you can understand how quickly the Evija can hurl itself into the middle distance, it is worth taking a moment to consider what’s motivating it – and exactly how. Take a notional modern, four-wheel-drive, combustion-engined performance car for comparison. One weighing roughly what our Lotus does. Something like a BMW M4 Competition.

Assuming the car in question has a driveline that distributes torque equally front to rear, when you select third gear the engine can probably gradually build up to send an effective 800lb ft to each of its wheels (accounting for the effect of the gearing). Which sounds like a lot, but then M4s aren’t slow.

The Evija is, in one sense, like a four-wheel-drive performance car that only ever needs third gear, because its motors can be permanently connected to its wheels, work from zero rpm, and rev to 17,000-. But each of them can – or, rather, could – send some 1800lb ft of effective torque to each of its wheels; do it from standing, the instant you asked; and then just keep on sending it for quite a long time without the slightest pause.

They also combine to make four times as much peak power as that notional car’s combustion engine could. And managing that kind of power and torque… well, it’s quite some way beyond the remit of the average traction control system.

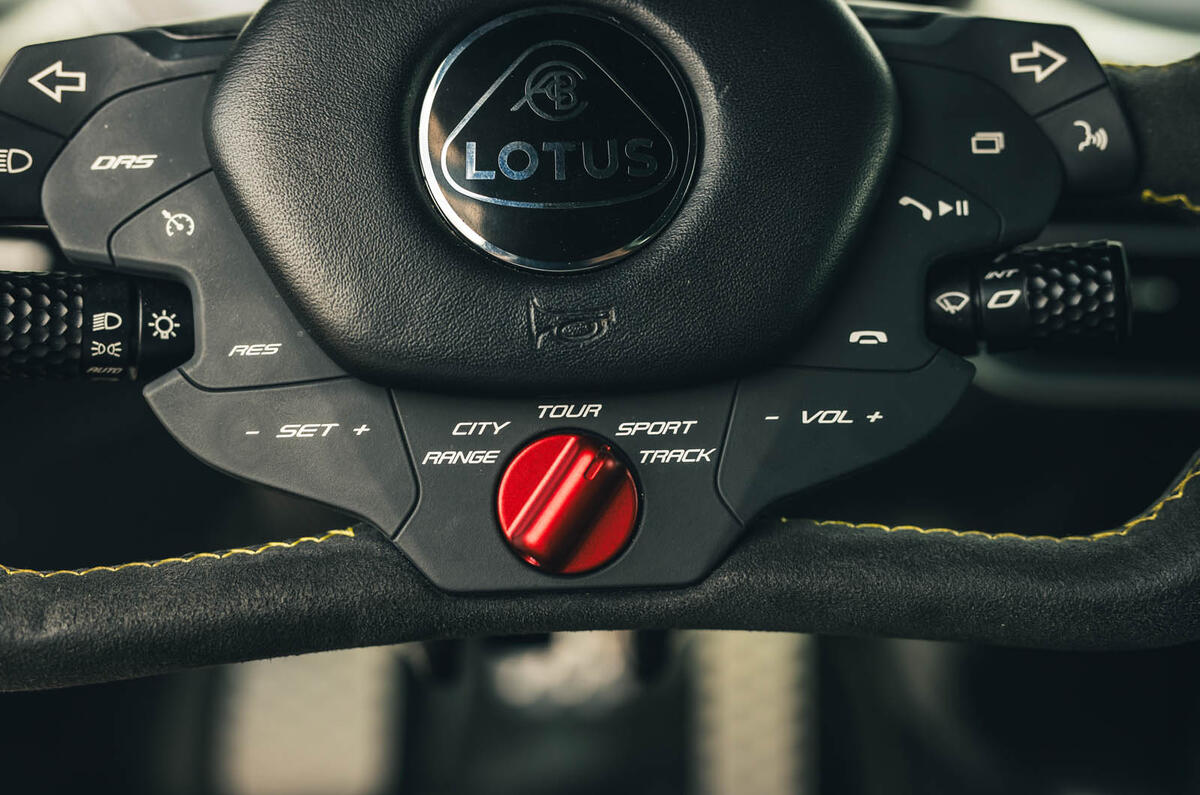

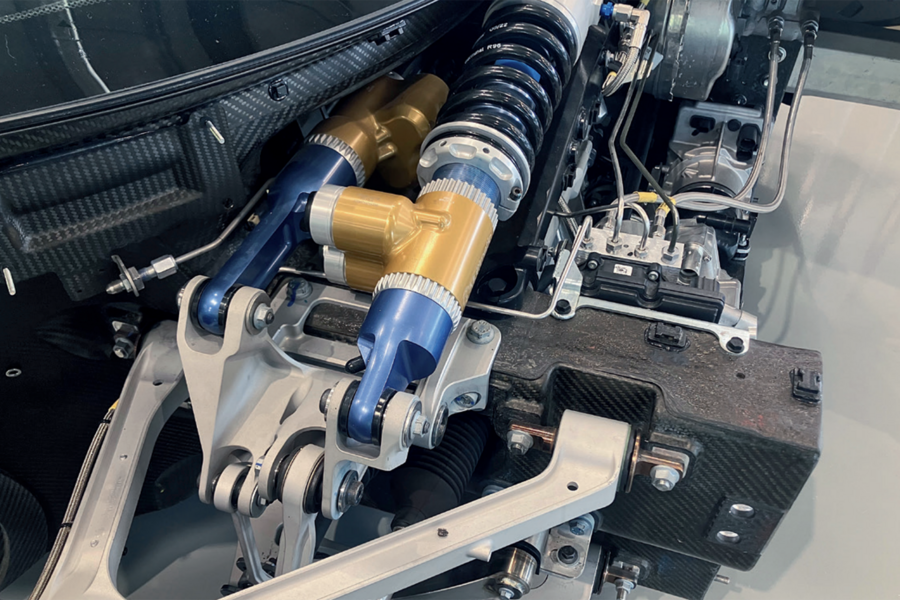

Without any kind of electronic governance, the Evija would be undrivable. Just floor it, and within about a second you would have four wheels, each rotating at a rate commensurate with 217mph of vehicle speed, and an uncontrollable car making a lot of smoke but going just about nowhere. That’s why the only system of equal influence on this car’s performance as its electric powertrain is its vastly sophisticated torque-vectoring and traction control system. It has to be. It is the supercomputer that keeps this fifth-generation fighter jet in the sky.

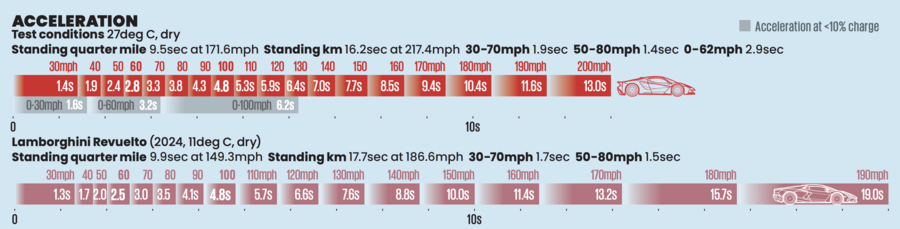

On the move and in full flight, the Evija feels less like one particular kind of performance car as it accelerates than three- or even four-. From rest to 60mph (2.8sec), it’s fast but not vastly excessive; perhaps supercar-fast. Thereafter, up to 100mph (which it hits in 4.8sec), it begins to gather itself and open the taps a little, taking on what we might consider established hypercar pace.

But only beyond 100mph does the Evija show its real potential - once there’s enough downforce on the front wheels for the electronics to fully unleash the front motors, which, like the rest, don’t even hit peak power until the far side of 110mph anyway. Even here, this car feels like it’s engaged in a constant and incremental process of unshackling itself; of pitching massive power and increasing downforce against available mechanical grip, mass and drag – with Herculean results. It just goes, and goes again… and then goes again, somehow harder still.

Giving a car like this its head, even in a straight line and with two lanes of a proving ground’s mile straights to straddle, is an exercise requiring a lot of faith and commitment. Preparation, too: you won’t want to do it before you have adjusted the pressure in the Trofeo R tyres, because cold, soft sidewalls inflated only to road-appropriate pressure simply won’t support the load, weight and building downforce. And driving on flat tyres at 150mph, with 0.8g of forward thrust still in the mix, isn’t much fun.

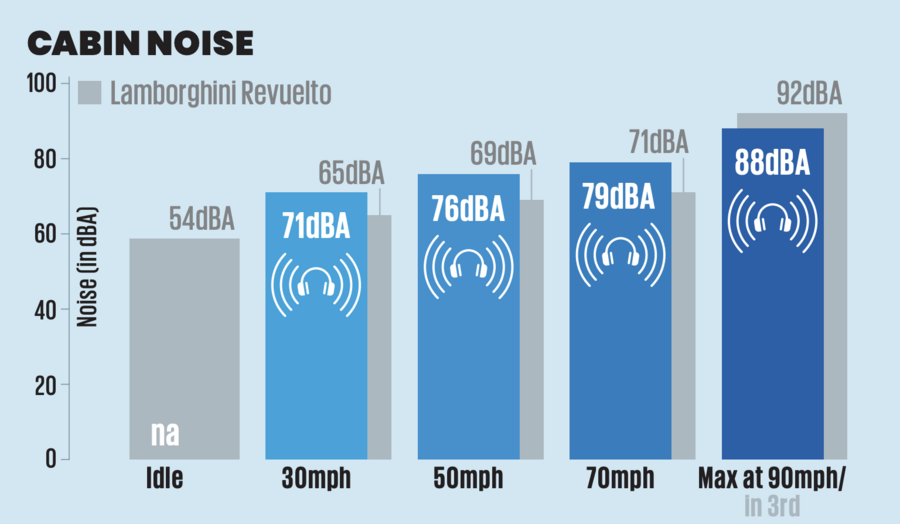

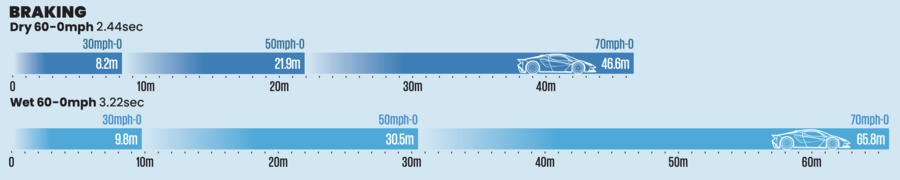

But, at its very quickest and when properly dialled in, this car is an utterly staggering, eye-popping drive. The steering wheel jinks with every bump and newly vectored slug of torque. The whistling, whirring, high-frequency whine of the motors and transmissions, quite dramatic and noisy at first, is gradually drowned out by the increasing, reverberating roar of the tyres and wind. Your focus is fixed on a vanishing point, but the world is hurtling through your peripheral vision at a frankly incomprehensible rate. And all you can do is pick your braking point – and be damn sure to hit it – and then contemplate what’s just occurred.