To drive the McLaren F1 safely on British roads, with consideration to other road users, required considerable mental discipline.

You had to accept that, save on empty autobahns, there was no way you could sample the F1’s performance potential safely and legally on a public highway. The truth was that, even for drivers of exceptional experience and skill, driving the McLaren fast in public was an exercise in restraint.

For this was a car that could exit a curve at 60mph onto a straight and, just 11.4sec later, be travelling at 160mph. This was a car that could accelerate from 100 to 200mph considerably faster than most quick cars could reach 100mph from a standstill. This was a car which, unless driven with a cool head, could land you in greater trouble than you could imagine.

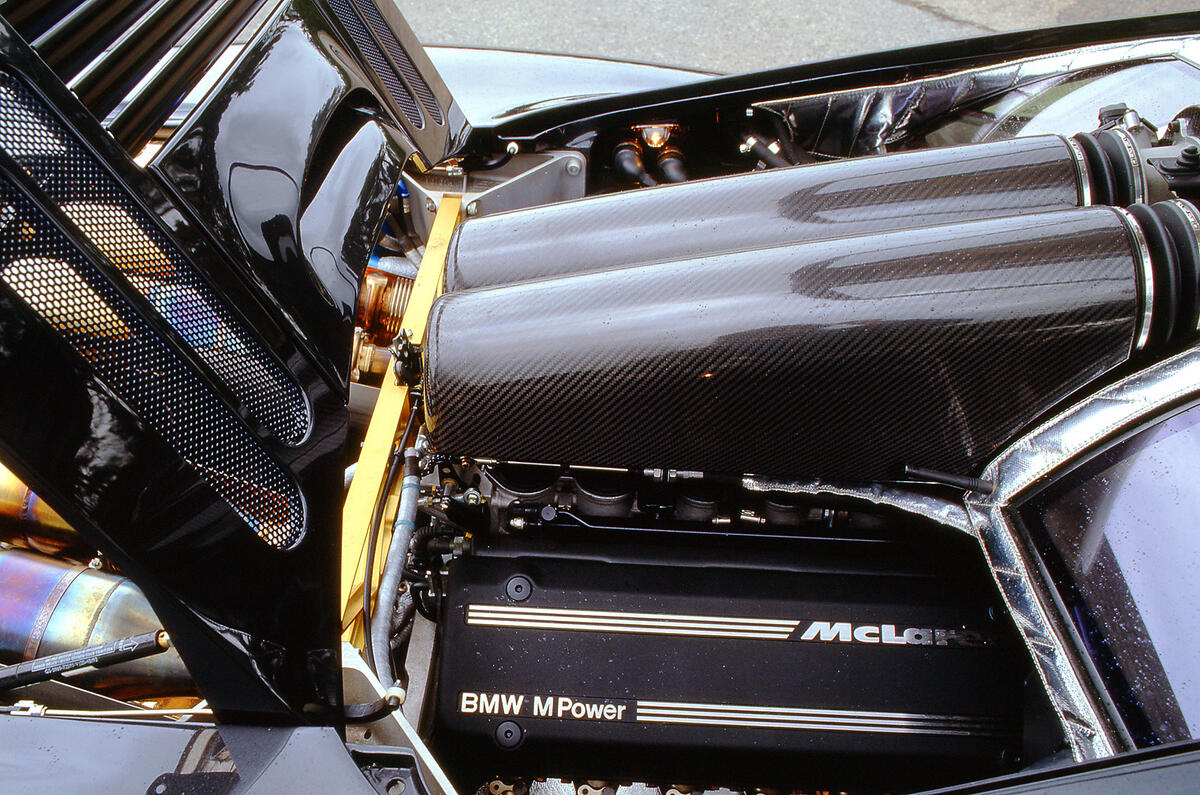

Happily, though, it was both simple and enjoyable to drive slowly. The engine, despite having a specific output of 103bhp per litre, the highest of any normally aspirated production engine, used its capacity and variable valve timing to summon huge chunks of torque from idle onwards.

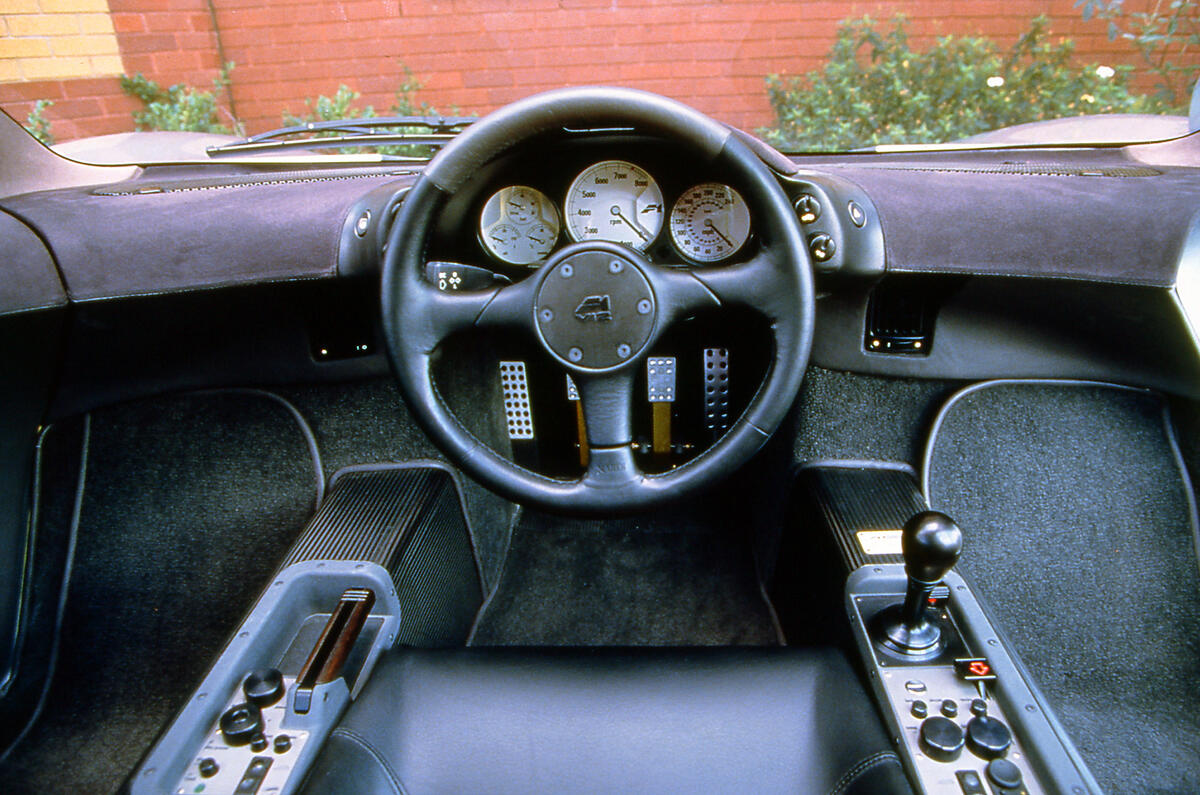

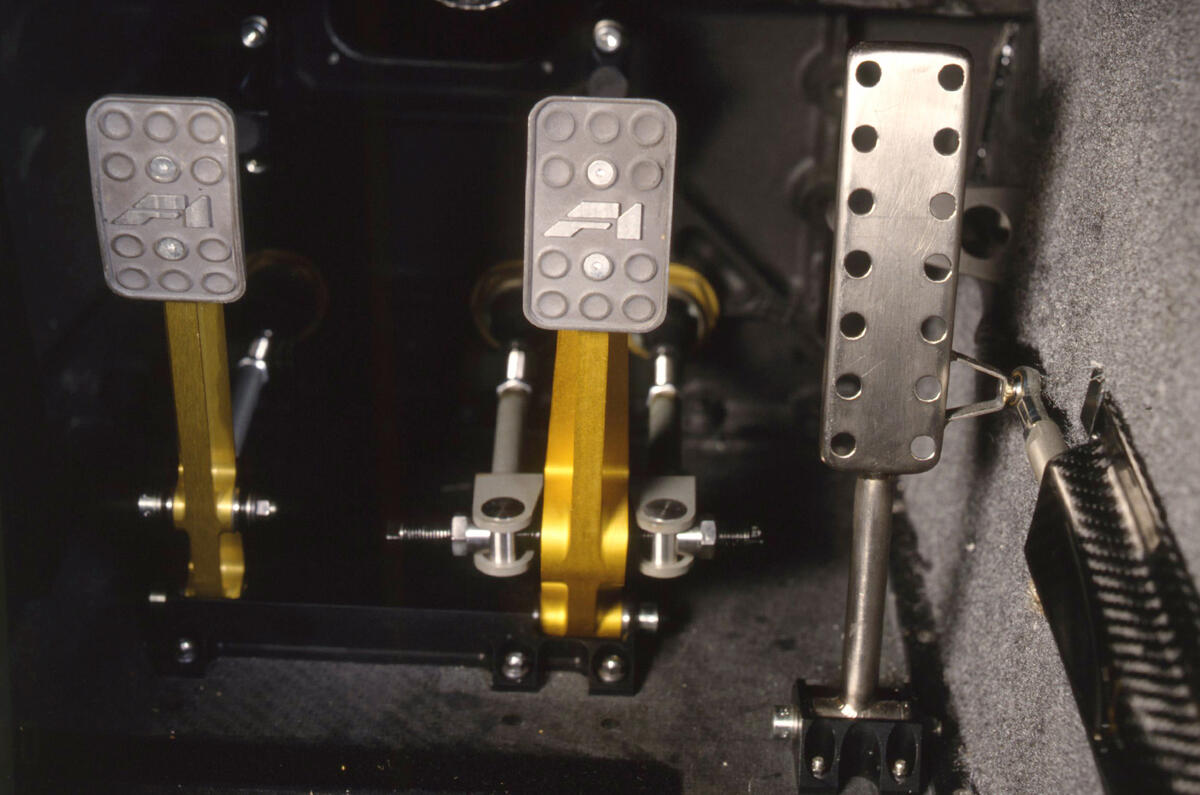

The clutch was a little lighter that you’d expect given the power it had to transmit. The engine had no flywheel so the revs didn't so much fall as vanish when you lifted your right foot, but so swift was the six-speed gearbox that changing gear smoothly was simple.

Threading your way through town, the F1 seemed almost sedate. Behind you the V12 whirred softly to itself, you adapted to the central driving position without thinking about it and, thanks to the F1 being no wider than a Toyota Supra, gaps were easy to negotiate.

Once you reached the city limits, you'd slot the lever into sixth and you spend hours wandering around the lanes at 60mph and 2000rpm. But this was not what the F1 was for.

We used two proving grounds for this test: first there was our usual visit to Millbrook in Bedfordshire to exploit the superb grippy surface that all our test cars enjoyed, then we left for the Bruntingthorpe test track in Leicestershire with its two-mile runway to record the performance figures that, of all production cars in the history of the motor car, only the F1 could have produced.

Starting a world record breaking acceleration run in an F1 was easier than you’d think. There were cars with considerably less than half the F1’s power that would prove trickier.

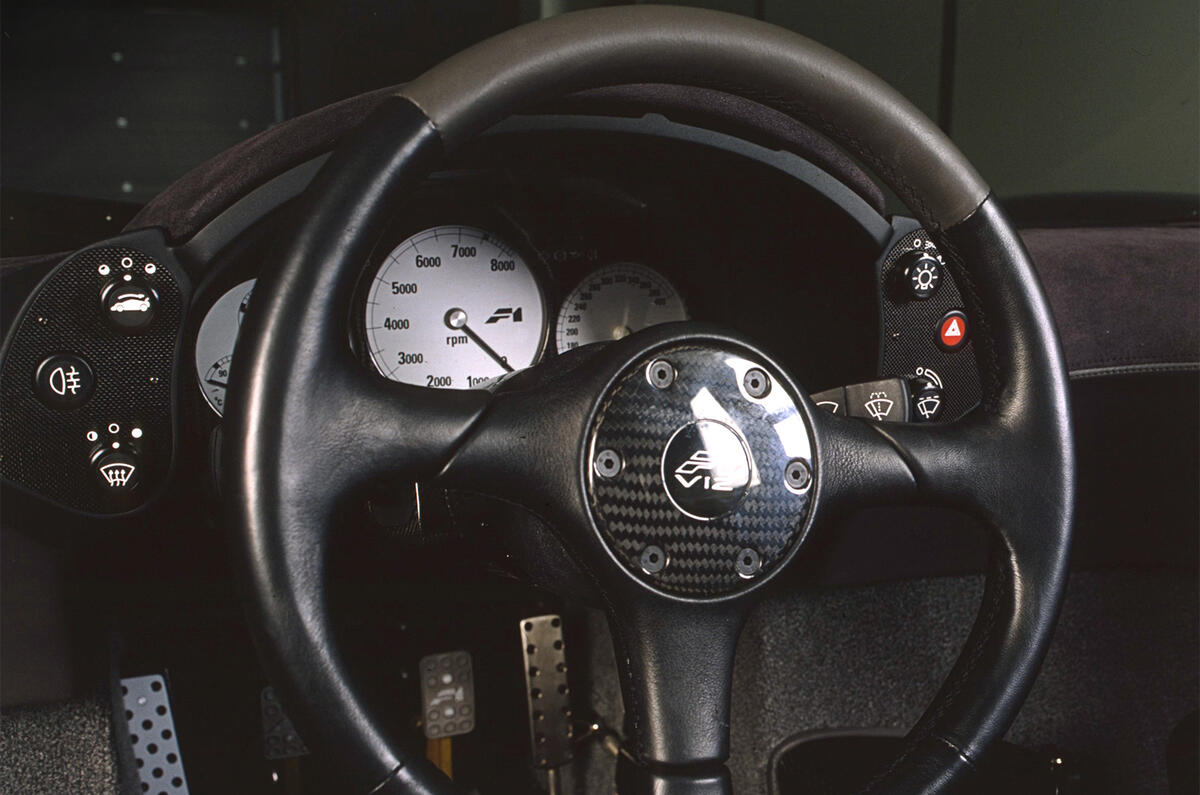

Because the engine had no turbos, just good old fashioned cubic capacity with an icing of high-tech variable valve timing, instant and reliable torque was available everywhere. You just called up about 2500rpm on the large, central rev counter and gently fed in the clutch.

If you got it right, your brain would be too preoccupied with keeping the rear tyres on the edge of wheelspin and the bark coming through the rear bulkhead to appreciate just how fast you were travelling. You needed to be quick with the six-speed gearbox to hook second before the engine slammed into its 7500rpm limiter.

But even before your left foot touched the clutch, you’d be doing more than 60mph, just 3.2sec from rest.

And only now would you start to appreciate how fast this car was because, until now, you’d only been using part throttle. How fast? So fast that it was actually uncomfortable on first acquaintance. As the car shot forward, the acceleration penetrated right through to your deepest internal organs. In second gear, the F1 added 10mph per each half second.

You’d pass 100mph in third, having been mobile for 6.3sec. The second-fastest car we had tested, Jaguar’s XJ220, asked for 7.9sec for the same measure. And still the McLaren was not in its stride.

It did 0-120mph in 9.2sec, a decent enough 0-60mph time for a hot hatch. It could reach 150mph from rest quicker than a then new Porsche 911 could reach 100mph. But the statistic to end them all was this: in sixth gear, it could cover 180-200mph in 7.6sec. A Ferrari 512 TR needed longer to do 50-70mph in fifth.