Caterham could hardly have picked a better week to send us its new retro-look Seven Sprint.

Two days earlier, I’d been summoned to the semi-detached house my grandparents called home before infirmity and chronic forgetfulness finally ushered them into full-time care.

With a place in the estate agent’s window beckoning, the immediate family were there to siphon treasured memories from a six-decade mountain of dusty clutter. Occasional poignant moment aside, this wasn’t difficult – until, that is, the jumbled shelves and ancient boxes of my grandad’s workshop spilled their secrets.

Read more: 2017 Caterham Seven Sprint review

Often still in their original wax paper or packaging, the most achingly beautiful hand tools, still sharp or shiny or else solid like a lump of basalt, tumbled from pre-history into the daylight of the disposable age.

Grandad, a talented worker of wood and a teacher of its assemblage when not lecturing about mathematics, had clearly completed his last buying spree in the late 1950s, a time when being well made and durable meant you came stamped with a ‘Made in Sheffield’ trademark and shone like stained glass.

He owned, among other things, a micrometer that makes a nuclear reactor core look flimsy, a hand plane of such absurd heft and forged metal splendor that my manliness literally trebled by holding the thing aloft to look at it, and an ancient yet functioning electric drill that started its life on the line at de Havilland, boring holes in the balsa wood and birch that made up the monocoque of a Mosquito fighter bomber.

Being a glorified typist, I have no practical use for any of this, of course – but the build quality, tonnage and overt imperial magnificence of the collection mean that I now own it all. And it is that magnetic wistfulness, I think, for the glow of the long-dead furnace at the core of Britain’s prewar and post-war workshop, and of the molten exceptionalism that it engendered for decades afterwards, that characterises the appeal of cars like the Seven Sprint.

It is a trick, frankly, that Caterham has too often overlooked in its compulsive reflex to make its single product go ever more indulgently (and profitably) quicker. But 2017 has given the company good reason to look back as it marks 60 years since the Seven made its debut at the Earl’s Court Motor Show.

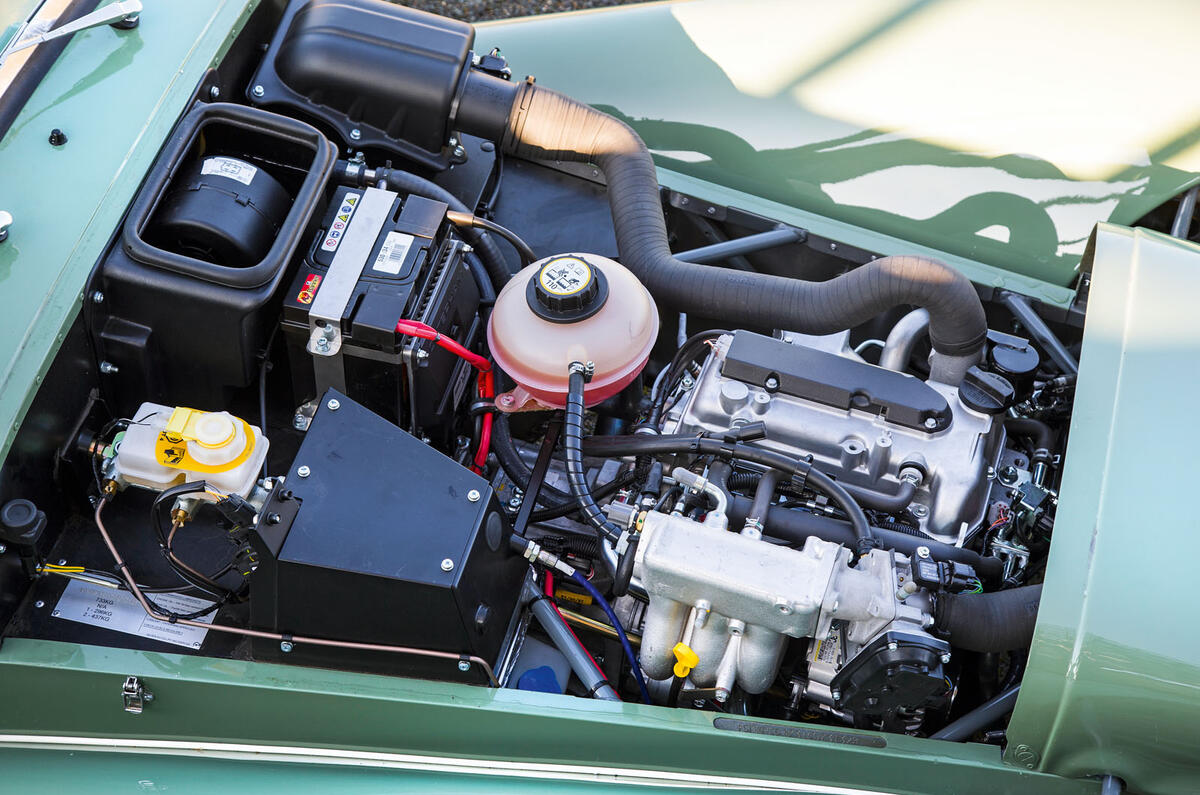

The Sprint bears little resemblance to the model that actually adorned Lotus’s stand that year. With its flared front wings, powder-coated chassis, wood-rimmed steering wheel and polished hub caps, the car is meant to celebrate the essence of the age rather than its substance. Underneath, it’s unchanged from the current entry-level 160, driven by an 80bhp, 660cc Suzuki three-cylinder engine and its corresponding five-speed manual gearbox.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Monster journalist. Bring

Bowler vs Caterham

Would have been interesting - if this really had been a seven