Performance benchmarks for the P1 are scattered thinly. Ignore the F12 (LaFerrari is the more sensible comparison) and look instead to an Ariel Atom V8, Bugatti Veyron Super Sport or, indeed, the F1.

That the F1 remains comparable today is testament to its purity; in third gear, it covered each 20mph increment from 20-110mph in less than 2.0sec; from 60-80mph it wanted just 1.6sec. We thought that its numbers would be the fastest we’d ever record. They weren’t.

The P1 is shorter geared in third, but it covers the same 60-80mph sprint in just 1.2sec.

If you want to go from 0-60mph faster than the P1’s 2.8sec, or from 0-100mph faster than its 5.2sec, or cover a standing quarter mile more quickly (10.2sec at 147.5mph and climbing fast), our road test records show that you’ll need a Veyron Super Sport or nothing.

But it’s the nature of the P1’s delivery, rather than its savagery, that is just as impressive. The Veyron introduced us to cars that were as powerful as 10 Volkswagen Golfs but as easy to drive as just one, and despite a much smaller swept capacity, the P1’s hybrid trickery enables it to retain those qualities.

The P1 fires to an extremely loud idle – there are cars that drive at 50mph with less interior volume than a stationary P1 – but apart from the volume, there is no hint of its 238bhp- per-litre specific output or 8250rpm rev limit. It’s a clean, civil engine note and initial response is fine, too.

You can pootle in a P1 without a barrage of wasted revs or pinking and crackles, and you can also accelerate briskly in high gears seemingly without any accompanying turbo lag.

For that, you can thank the electric motor’s 192lb ft of torque, which fills the void left while the turbos spool. As a result, the P1 feels like a car with a much larger capacity and it generates peak torque at just 4000rpm. In fifth gear, it’s as quick from 50-70mph as it is from 120-140mph (2.7sec, since you’re asking).

Flick the powertain switch through Normal to Sport or Track modes and you’ll increase the gearshift ferocity. Engage the ‘boost’ function and at near-full throttle openings you can extract maximum performance by pushing the IPAS button, which releases the electric motor’s potential (which is also on tap via the throttle without ‘boost’ engaged). Race mode we’ll come to in a second.

In the dry, all of this performance is accessible. In the lower gears, it gives the deftly judged traction control a hard time, but dry traction is always impressive. Such is the severity of the initial acceleration allowed by the launch control system that rolling on to MIRA’s mile straight at, say, approaching 70mph (no more is possible) buys only 5mph at the far end compared with a standing start. (This all assumes that conditions are dry, of course. In the damp, the P1’s acceleration troubles the electronics, even in fifth gear.)

What use is performance like this on the road? Well, as one McLaren executive told us, you don’t have to use all of the throttle. It’s not a switch, and nor is it non-linear. It’s perfectly easy to meter out, and the dual-clutch gearbox operates as swiftly as we’ve come to expect. On bigger throttle openings, the electric motor not only boosts torque but can also reverse its rotation and pull revs back down between upshifts, and it helps to blip on downshifts.

And although the P1 never automatically cuts the engine to drive on the motor alone (you’ll never start a 727bhp V8 as cleanly and quietly as you can a 1.5-litre Toyota Prius’s four-pot), you can select an all-electric drive mode, in which the P1 is merely brisk.

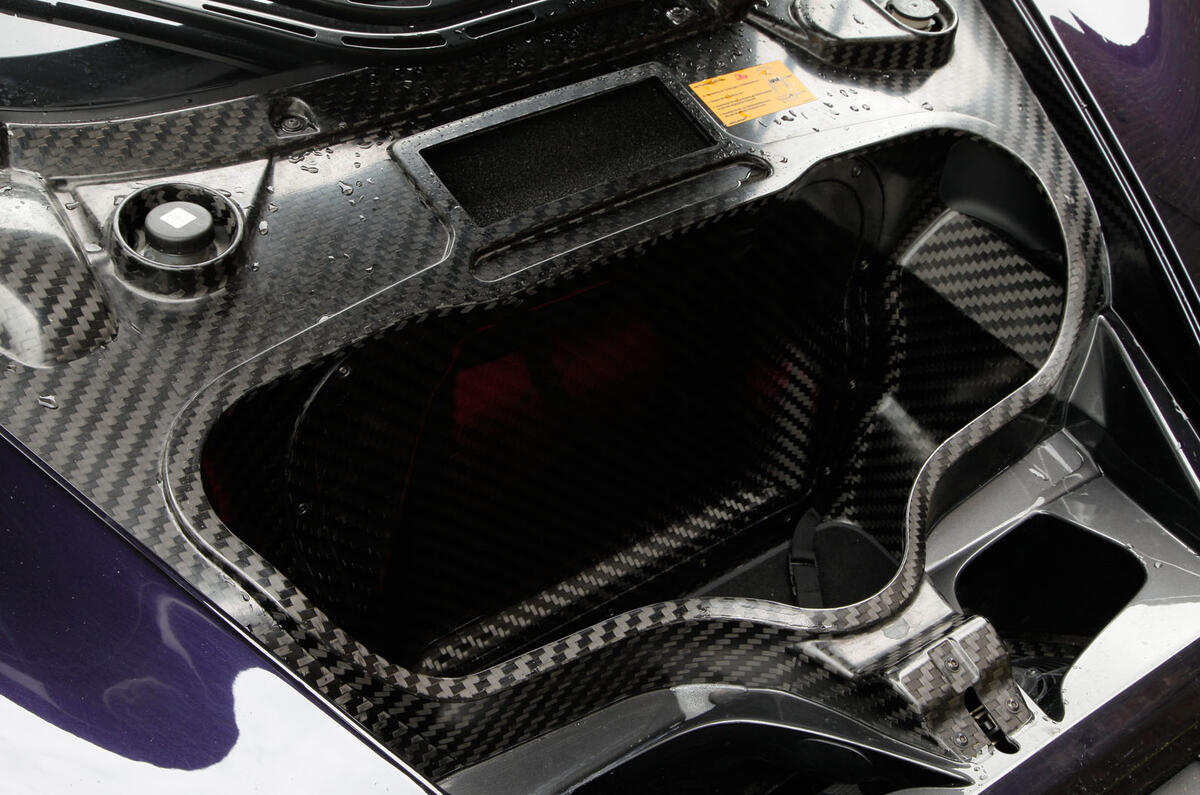

McLaren says this is useful if there’s a city in which you cannot drive an internally combusted vehicle, but given that the electric range is only six miles, it’s hard not to think that McLaren really made it just because it could and thought it would be fun. If a million-dollar car can’t be a bit of fun, what can be?

In electric mode, the noises are more space port than race track, but in any mode the P1 sounds unusual; rather than explosions, the sound is dominated by vast quantities of air being inducted or forced through the turbochargers. It’s not traditionally intoxicating, but it’s pleasant enough.