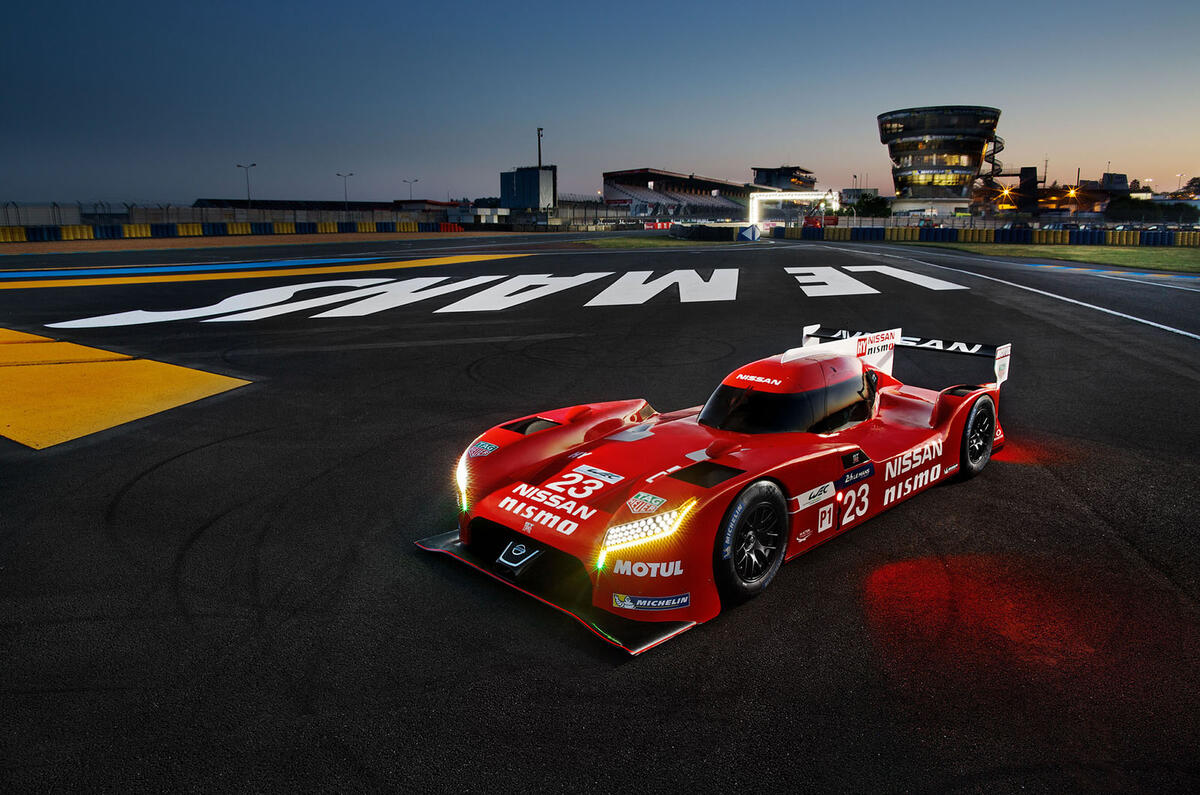

Had Nissan decided to return to the top class at Le Mans with a conventional racing car – that is to say, one with an engine in the rear sending power to the rear wheels – its return would have been greeted with much enthusiasm.

However, it is mounting an assault on the famous endurance race with a car that has flipped perceived wisdom, putting the engine in front of the driver and sending a prodigious amount of power to the front axle, and this has provoked reactions of astonishment, praise, amusement and even a touch of confusion.

Since lifting the dust cover from the GT-R LM Nismo, Nissan has become the most talked-about manufacturer in endurance racing. (The company has people who monitor this kind of thing.)

Not all of the exposure has been comfortable reading. Naysayers wondered if inherent understeer would leave the car struggling.

Others scoffed knowingly when it failed its initial crash tests, forcing the postponement of warm-up races at Silverstone and Spa, and when it lapped Le Mans almost 30 seconds slower than the pace-setting Porsches during last month’s test day.

But Nissan’s motorsport chiefs – led on the sporting side by Darren Cox and on technical matters by Ben Bowlby – have got used to the Marmite reaction to its project.

They’ve seen it all before with the similarly radical ZEOD project, which ran at Le Mans last year. In fact, they positively encourage the glare of publicity, exposing their team’s inner workings via social media in a manner that has rarely been seen in modern motor racing.

Mind you, they are deflating public expectations for this weekend’s race. Simply making the grid is an achievement for a project that was only signed off by Nissan’s board in April 2014.

Since then, Nismo has built the team from the ground up. The LMP1-class car has been designed and developed, three race-ready examples built and nine racing drivers signed, among them three graduates from Nissan’s GT Academy training scheme: Jann Mardenborough, Mark Shulzhitskiy and Lucas Ordonez.

It’s a tight enough timeframe, one made more acute by the ambitious technical layout. Bowlby, renowned as one of the sport’s keenest lateral thinkers, explains the reasoning for putting the engine in the front: “The brief was that if Nissan was going to do LMP1, it had to be innovative. Audi is 15 years and billions of dollars into this, so why bother to go motor racing when one team is so tightly dug in?

"The Le Mans rule book has plenty of scope for innovation if one is bold enough. It was clear to me that there was an extremely intelligent solution in moving the engine to the front and making it front-wheel drive, with front-wheel brake energy recovery that deploys to the rear axle.”

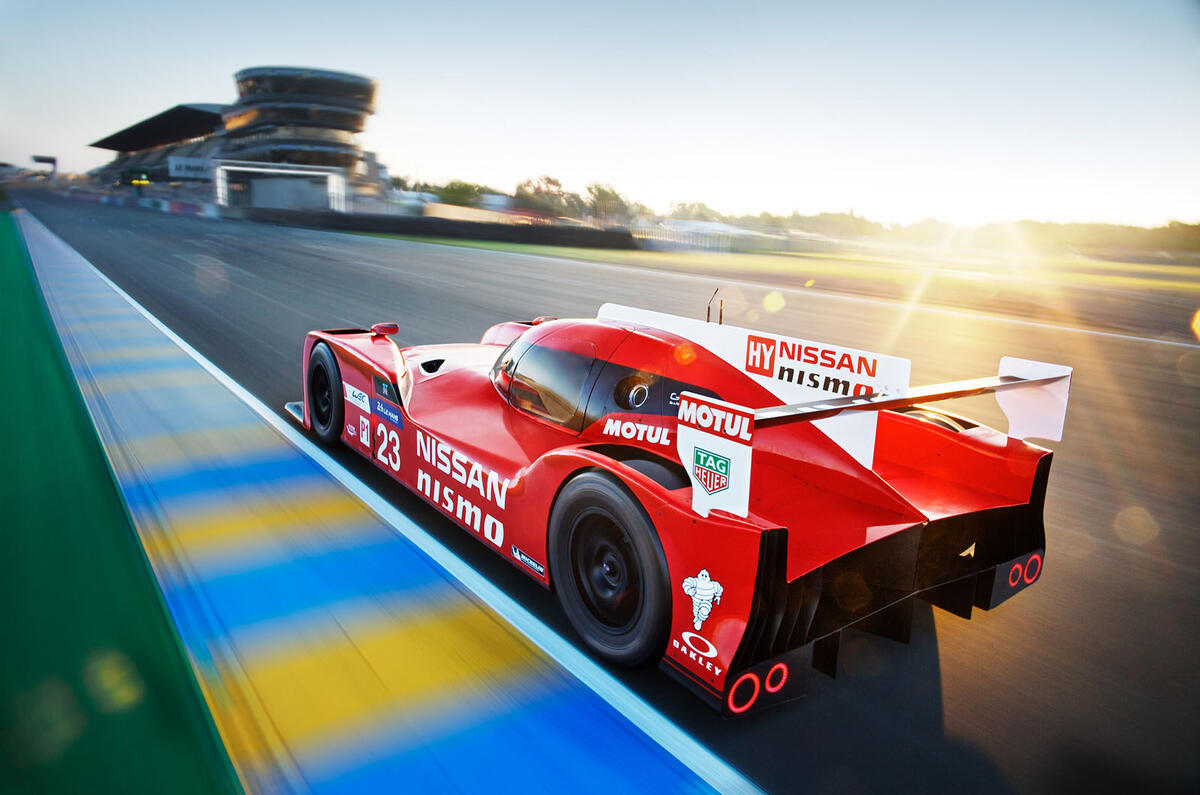

When dreaming up his LMP1 car, Bowlby noted that the current crop of Le Mans prototypes are limited in their rear-end designs.

“To limit the performance of rear-engined, rear- wheel-drive cars, the rule makers have constrained the sizes of the rear wheels, wing and diffuser, and the result is that the aerodynamic efficiency at the back of the car is quite poor,” he explains.

Join the debate

Add your comment

A blast from the past

Yeah, but why?

Yeah, but why?