If there were a world championship for spotting top driving talent, Bill Sisley would be a serial winner.

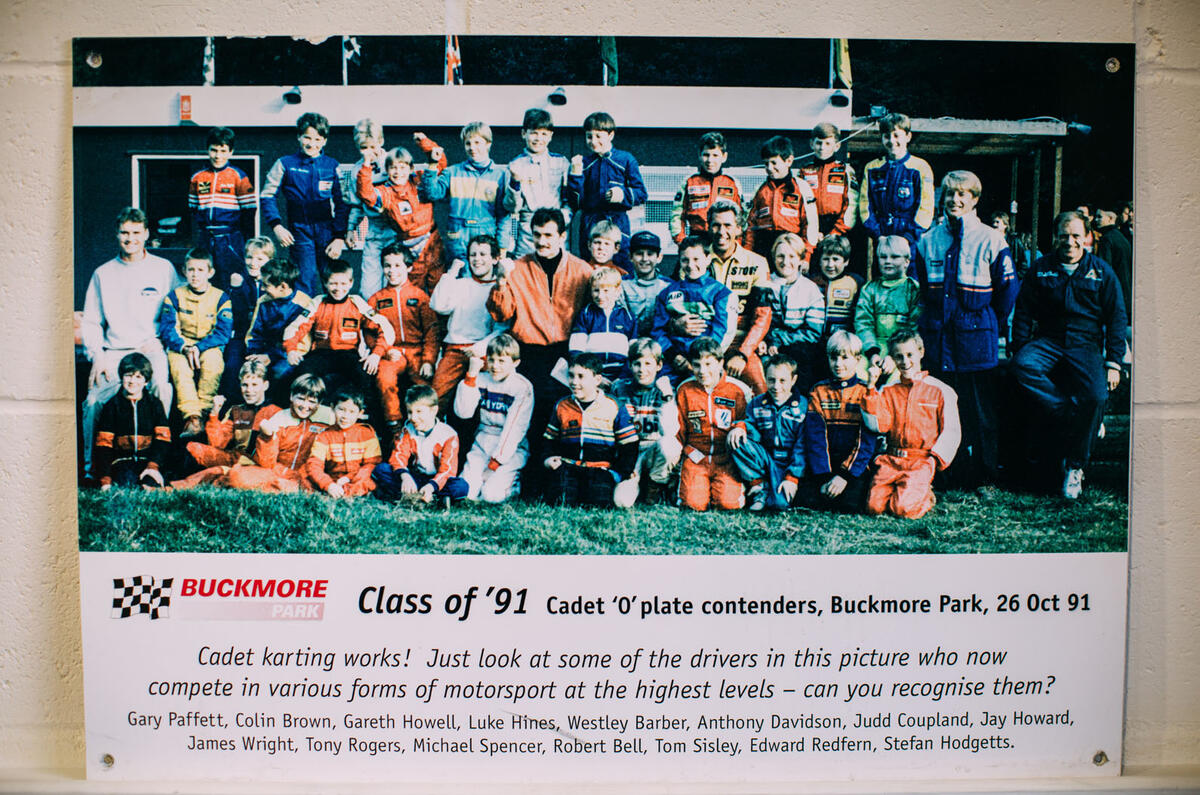

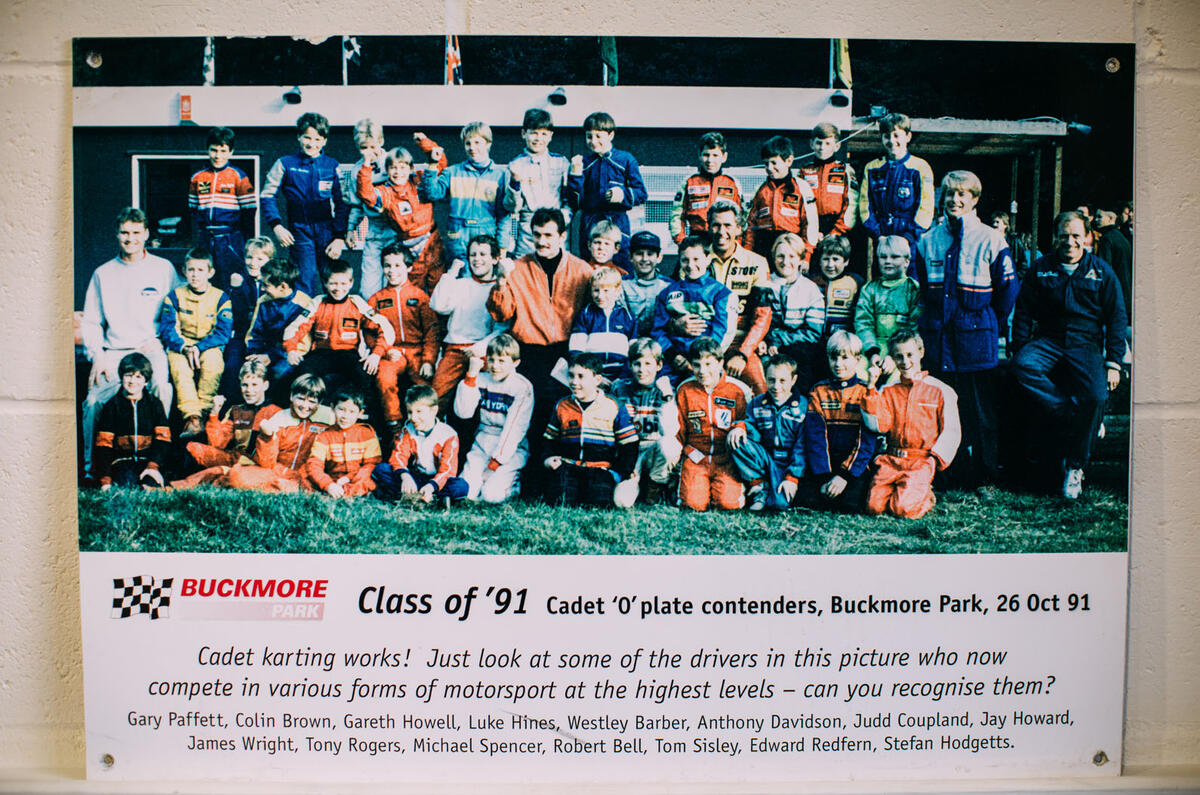

Drivers chosen by Sisley for their ability behind the wheel – often spotted before their 10th birthdays – have gone on to win multiple Formula 1 world titles and dozens of grands prix. Others have become IndyCar champions or reached the highest echelons of world sports car racing.

The parade of Sisley stars began in the 1970s with Johnny Herbert and then expanded through the 1980s and 1990s with Jenson Button, the late Dan Wheldon, Lewis Hamilton, Anthony Davidson, Gary Paffett and Bills’s own son Tom, who was as good as any. All came to prominence very young and many are still racing.

“You can see talent at the very beginning, if you know what you’re looking for,” Sisley says. “Driving ability doesn’t change. A star is a star from the beginning, but you’ll never make a slow driver fast. Of course, drivers learn to race better as they gain experience, and the clever ones – Nico Rosberg is a great example – learn to channel their talent. But it takes just one race to spot someone who’s really got it.”

So sure is Sisley’s judgement that even today, 62 years old and semi-retired, he is still approached by parents who believe he can help their kids join the greats. Sometimes they offer big money, but Bill always demurs. “I’ve only ever done it once,” he says, “when Bernie Ecclestone asked me and I did it for obvious reasons. But it didn’t work out too well; the guy couldn’t drive.”

Sisley believes his knack as a talent spotter has come about through a life-long immersion in the sport; time spent as a driver, mechanic, manager, dealer and promoter. It began in the 1960s when his father drove stock cars and introduced him to karting for fun. At the time, his parents were paying big money to send him to public school and hoped he’d go to university.

“My contemporaries went to Oxford and Cambridge, and I suppose I could have done,” he says. “But I was mad on motorsport and not very academic. So I left school and went to work for a family friend, John Brise, who had a karting and racing business. That caused some awkwardness, I can tell you.”

See our top motorsport moments of 2015

By 18, Sisley was a Formula Ford mechanic working for John Brise’s son, Tony (later to die with Graham Hill in an aircraft accident). By 21, Sisley was married and still racing karts, but he had set up his own business selling spares around the country from a Transit van. It worked so well that after a couple of years he was able set up the nation’s first ‘smart-looking’ kart shop in Swanley, Kent, making good use of the head his wife, Penny, had for business.

Add your comment