Given that we’re discussing a car which today sells for eight times its 1993 launch price, it seems ridiculous that the remarkable McLaren F1, the 20th century’s king of supercars, should for a while have been viewed as a failure.

When production began in 1992, McLaren declared it would make 300 F1s. But when demand petered out and work stopped a couple of years later, the tally stood at just 90 cars, including half a dozen factory racers. It looked as if Woking had dramatically overestimated the world supply of car-minded billionaires

Today, this miscalculation won’t bother those who bought an F1. While they paid a little over half a million pounds in the early 1990s, a car sold at auction recently raised £4.5 million – not only eight times the F1’s original asking price, but five times more than is being asked for the new P1, the F1’s spiritual successor, unveiled just a week ago in Geneva.

Twenty years ago Autocar was given privileged access to the F1’s creators, led by chief engineer and technical director Gordon Murray and designer Peter Stevens.

We featured the car six times on covers through 1992 and 1993 and also produced an 80-page special supplement. So close was our co-operation that the performance figures for our world-first road test in 1994 were adopted by McLaren as its official factory standard.

They told an astonishing tale: a top speed of 230mph-plus, 0-60mph in a shattering 3.2sec, 0-100mph in just 6.3sec and 0-150mph in 12.8sec. It was literally the fastest production road car you could buy, with the highest price.

The giant presence behind the F1 effort, McLaren chairman Ron Dennis, stayed mostly in the background, partly because he didn’t know as much as he now does about building road cars for the super-rich, but mostly because he was still heavily involved in grand prix racing.

Even so, a large helping of credit for the car’s appearance must go to him, and to McLaren’s other money men of the time, Mansour Ojjeh and Creighton Brown, for giving the green light to a programme that inspired Murray and possibly stopped him heading to a rival grand prix team.

Leading the company

Even then, Dennis now says, he had his eye firmly fixed on evolving McLaren into a road car company surrounded by a wider technology group, the kind of firm it has become in recent years. “I’ve wanted to lead a company making road cars for so long that I’ve forgotten when the idea first came into my mind,” says Dennis.

When we met in his Guildford studio to talk McLaren F1, Murray insisted the car was never built to win notice for its top speed. If that had truly been the issue, he says, they wouldn’t have given it the “relaxed, tickover top gear” that went into production.

“The F1 was born with three goals,” Murray explains. “One was to solve the problems inherent in most supercars: bad seating position, lack of visibility, terrible pedal offsets, no space to carry stuff in the cabin, poor luggage space, no decent sound system or air conditioning.

“Another was to enhance the driver’s experience. It seemed to me supercar design was being dictated by performance figures, whereas building a really great driver’s car is a much more emotional thing than figures on paper. We knew the F1 would be fast because it would be small and light, but we didn’t dwell on that.

"My original notes called for a V10 or V12 of about 450bhp; it wasn’t until my pal Paul Rosche, BMW’s top engine expert, proposed a very compact 6.0-litre V12 that we knew it would be as quick as it was.

“The third thing was to make the most of the central driving position – to really focus on giving owners the best possible driver experience. The F1’s layout allowed us to concentrate absolutely on driver location and comfort, and it worked. We found you could move the driver about a foot forward and give him a very low cowl that gave great vision.

"You could also hide all the stray bits and pieces – washer bottle, ventilation system and even air vents – in the nose so you were left with a pure, fighter-style cockpit, something owners still love.”

A project from out of the blue

Peter Stevens, the F1’s designer, says the project arrived out of the blue. “It turned up at just the right time,” he says. “We’d done the Lotus Elan, and at night I’d been working on the Jaguar XJR15 for Tom Walkinshaw. But when those projects ended, there wasn’t much else on the horizon.

“One night Gordon rang and said he needed my advice on a designer for the new McLaren road car. I knew nothing about the F1 except what I’d seen in Autocar. Gordon told me they’d thought about using the Italian studios, but really wanted someone to work with them on the job. I knew Gordon socially because I’d been drafted in by Bernie Ecclestone to design graphics for some of his Brabham grand prix cars. After a few beers, I told Gordon I had just the name he needed: me. We shook hands on the deal that night.”

With a small design team, Stevens worked full time at McLaren for more than a year. Arriving at the final shape took only about three months, but before that Murray and Stevens did about nine months of packaging work – starting with a three-person seating buck – to decide exactly the proportions of a car they needed to build. “I produced half a dozen different simple front and rear ends, all to suit the same seating buck,” Stevens says.

Murray was “fanatical” about keeping weight down, and everyone knew that if you had too much car, you had too much weight. “We’d looked at the Lamborghini Countach and the Jaguar XJ220 and knew we didn’t want anything like that,” he says with typical candour.

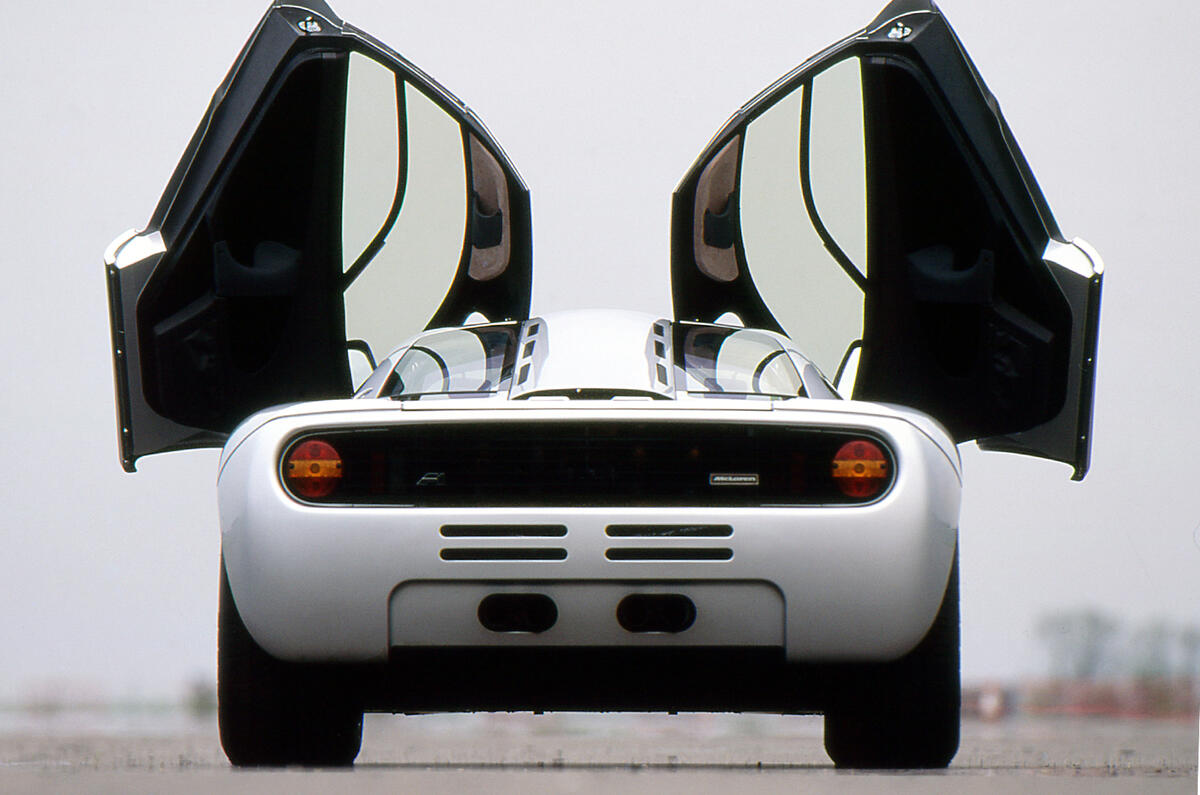

Stevens also loved the central driving position. “It made a terrific difference to driver comfort,” he says. “It’s subtle, but getting the details right adds up to an enormous benefit in driver comfort and confidence. We also found we could place all the controls, switches and dials – not to mention big stuff like the right-hand gearchange – in exactly the right places.

"And there was another benefit: a central position lets you place the car with fantastic accuracy on the road. I can remember realising this the first time we ever rolled the mock-up around the workshop.”

Only after months of packaging and aero work did Stevens get serious about finalising the car’s shape. “The sequence was unusual, but deliberate,” he says. “We didn’t want to build something we liked too early, then have to put ‘bandages’ on it to make it fit the package. There are too many examples of designers having to force a shape over such a car.

“We didn’t do lots of scale models, but our sketches were more realistic than you’d see today. Three of our four principals – Ron, Mansour, Creighton – weren’t that used to looking at sketches that simply convey a feeling. So we showed them as exactly as possible what they would be getting.

“When the car was first revealed to the public at the 1992 Monaco GP, I got the feeling Ayrton Senna, who was driving in our team at the time, was inspired at least to some extent by it. I remember him saying he felt he had to win this race because a company that could make this car needed his best effort. Our car wasn’t the best. But he was always fantastic at Monaco, drove out of his skin and won anyway.”

An F1 driver takes the lead

Soon afterwards, another big name entered the story. Jonathan Palmer had just retired from grand prix racing and was chief test driver of the cars raced by Senna and Gerhard Berger. He was made lead development driver of the F1, then head of marketing for the car, because his credentials gave him instant credibility with the customers and no one else could demonstrate the car so well.

“I’ve got such fond memories of the F1,” Palmer says. “The 6.0-litre V12 sounded phenomenal and had instant throttle response. The official 0-100mph time was 6.3sec, but if you got bored with that, you could show off the car’s torque by doing a 0-100mph run in one gear – third – which still only took 11.0sec. Mind you, the car had some issues early on. Gordon was keen to make it comfortable, and it was soft and pointy until we did some revisions.

“I remember being at Nardo, doing high-speed testing, sitting at 200mph for 10 minutes at a time, with some BMW kid with a laptop sitting in the passenger’s seat making adjustments to the engine mapping. It’s funny how you can get used to such speed. But Nardo has a hands-off speed of 150mph, so we were cornering all the way around the five-mile lap. Once, after the passengers got out, I gave it everything there was.

"Eventually the speedo showed 237mph, which the experts worked out at a true 231. But when I lifted off, the car was all over the place. We learned a lot right there about early balance issues but went home elated by how quick and slippery the car was.

“The F1 was an awesome car. Looking back, I’m even more pleased and proud to have been involved, and I loved it at the time. Not that everything was roses; we had big issues to cope with. But what Ron and Gordon achieved seemed amazing then and it’s still amazing now.”

Autocar has produced digital books on the McLaren P1 hypercar as well as the F1 and 12C supercars.

Download the McLaren F1 digital edition.

Join the debate

Add your comment

XJ220 - The Greatest?

XJ220 was comprimised in many

A benchmark hypercar

Lanehogger wrote: Whether

Incorrect assumptions