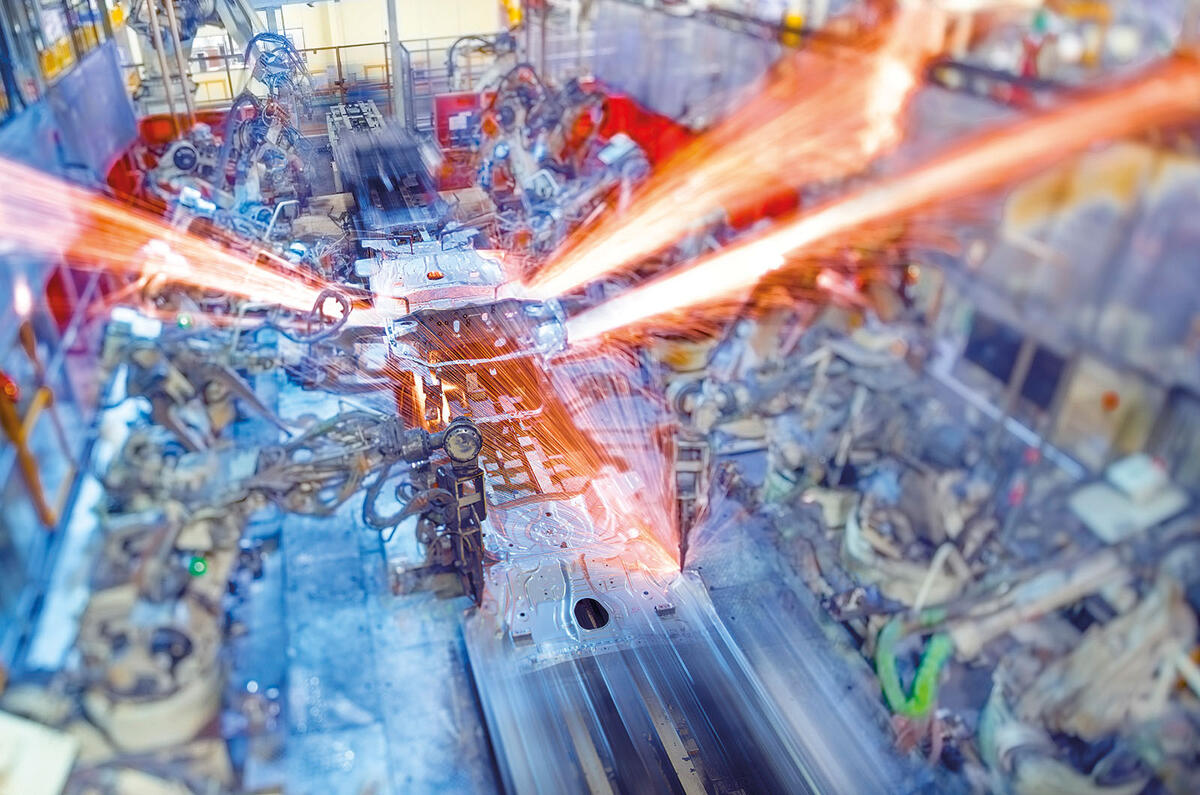

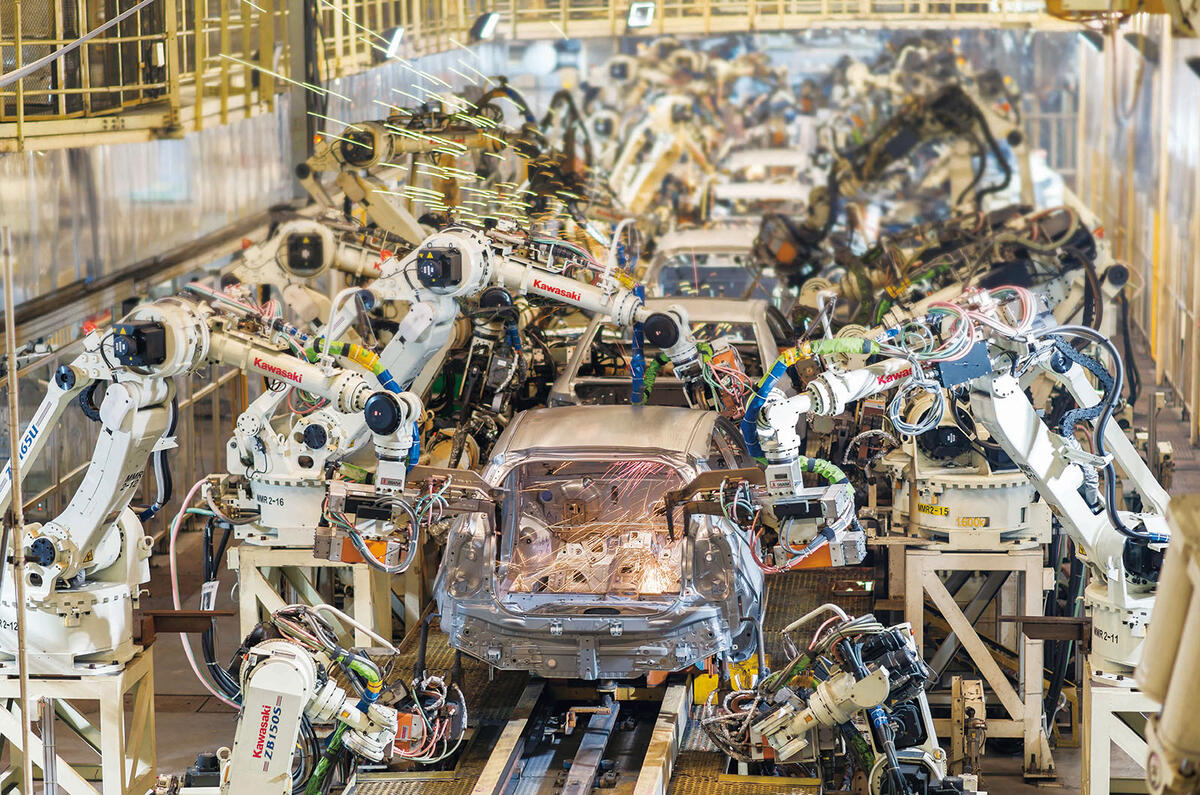

Toyota has long been recognised as the king of production line philosophy.

The highly influential Toyota Production System (TPS) was developed and refined over the decades after World War 2 by the Japanese company.

It’s widely held that Toyota – primarily in the form of company founder Kiichiro Toyoda and engineer Taiichi Ohno – also came up with the principle of ‘just-in-time’ production, which was a further advance on TPS.

The success of these philosophies was so all-encompassing that Toyota was called in to advise Porsche at the start of the 1990s, when the German manufacturer was close to collapse.

Some of the principles involved became well known across the world. Phrases such as ‘Kaizen’ (roughly, continuous improvement) and ‘poka-yoke’ (systems to prevent errors) became common currency in academia and business schools. Indeed, attempts were made to adapt what began in the car factory to improve the functioning of all sorts of businesses, many not remotely involved in manufacturing.

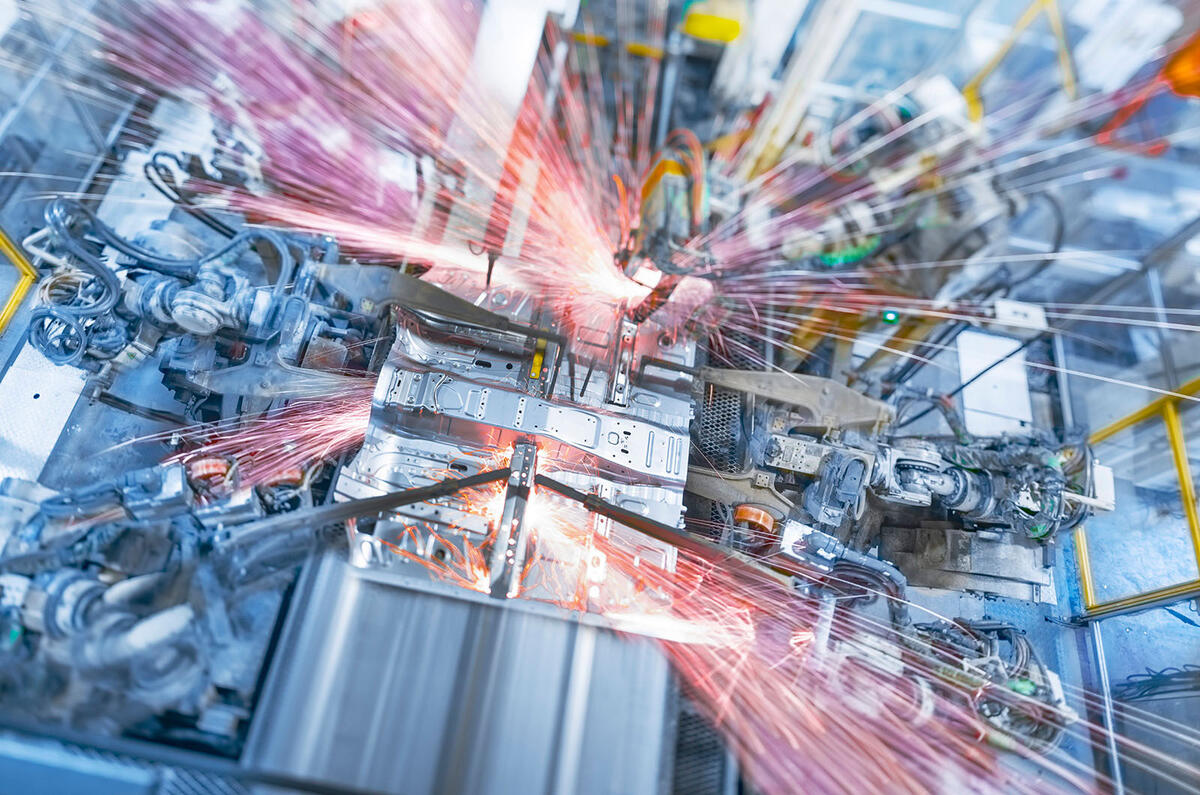

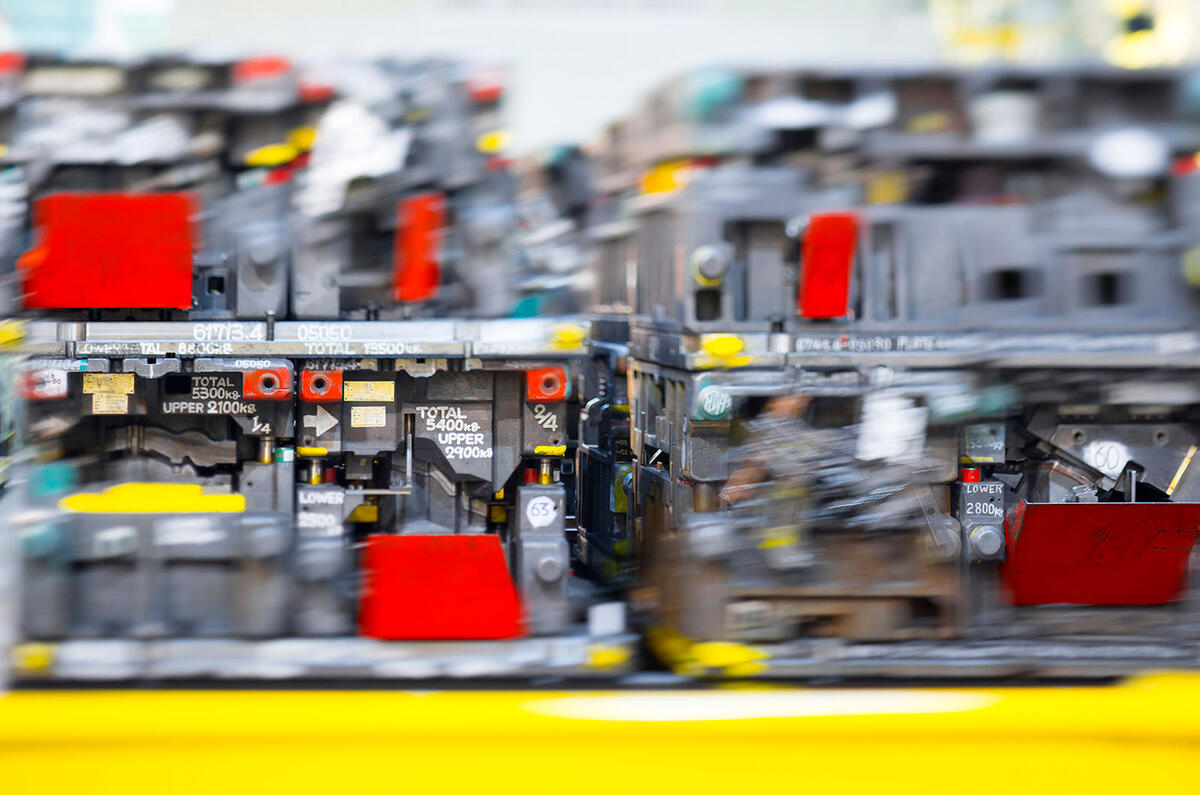

Ultimately, the TPS is based around the idea of eliminating waste of all kinds during the production process. The ‘wastes’ have been boiled down to seven broad categories. These include over-production, too much stock, too many manufacturing operations, delays in the flow of components and what’s called the ‘production of defects’. The idea of stopping a whole production line until a fault was fixed was another widely adopted Toyota innovation.

The rise and rise of just-in-time production has probably done most to change the face of car manufacturing over the past three decades. Toyota’s principle of having components arrive just in time at the production line, so they could be fitted immediately, has led to the growth of huge supplier parks around factories.

However, Toyota has spent the past four years in a root and branch rethink of the principles of mass production, resulting in what is arguably the most significant reboot of the modern production line principle since Henry Ford’s 1913 Model T line began rolling.

It was, executive vice-president Mitsuhisa Kato told Autocar, the fall of the Lehman Brothers bank in 2008 (it collapsed, helping to trigger the credit crunch that followed) that made “Toyota stop and change direction”.

Toyota’s internal figures show that, in the wake of the global recession, sales collapsed from more than 8.5 million units in 2007 to less than 6.4m in 2009. Now, considering the extent of that recession, you might think that shifting that many new cars was an impressive achievement. And maybe it was. But the nature of mass production means that factories have to be run at more than 75% of their capacity for a manufacturer to have a chance of making a profit.

Join the debate

Add your comment

The Kaizen system was used in

Is even 100k units pa quite