Diane Miller, Stellantis’s top UK car manufacturing executive and winner of Autocar’s 2025 Editors’ Award, has loved cars all her adult life – preferably in very large numbers – and can vividly remember the day the obsession began.

From a post-graduate job at Ford’s then mighty Ford Fiesta plant in Dagenham, Essex, Miller has spent the past 30-odd years mastering ever more responsible automotive jobs around the world – for Ford, Aston Martin, GM and most recently Stellantis, in the UK, Europe and the US.

Miller is decisive but modest and as a result reluctant to identify any particular secret of success. But if you converse with her long enough, she will eventually admit to one asset: “Finding a way to get on with people.”

It is for this that she is known and loved by the people who have worked for her. Having discovered its effectiveness early on, she has deployed her liking for people in every car job she has had, and she has become famous for it.

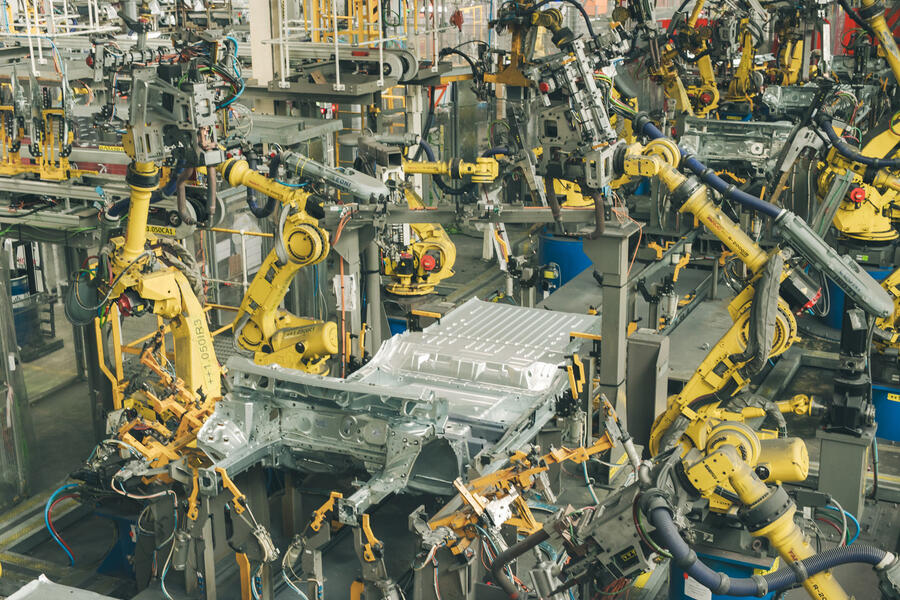

Miller’s most spectacular achievement to date has been the 18-month conversion of the former Vauxhall Astra plant at Ellesmere Port, near Liverpool, to the manufacture of battery-powered delivery vans for five Stellantis marques: Vauxhall, Opel, Citroën, Peugeot and Fiat.

It has been a vital move in rescuing volume vehicle manufacturing in this country. Now that this EV factory conversion has been achieved, Miller is turning her hand to running Stellantis’s massive new national parts distribution centre, located just down the road from the van plant at Ellesmere, where the company is spending £500 million to expand and improve the way it delivers components to its customers in the UK and Ireland.

The parts centre project has required another wholesale reorganisation, entailing both the redeployment of car-making people and the importation of new workers into a business that, despite its size and scale, has to be very labour-intensive.

It is a perfect place for a unique character like Miller, a highly experienced engineer who discovered early how to get on with people.

“I went to an all-girls convent grammar school in Northern Ireland,” she explains, “and three of us opted for A-level physics. Our teacher loved engineering, and the upshot was all three of us chose engineering at university: mechanical and production engineering for me; civil and aeronautical for the others.

Add your comment