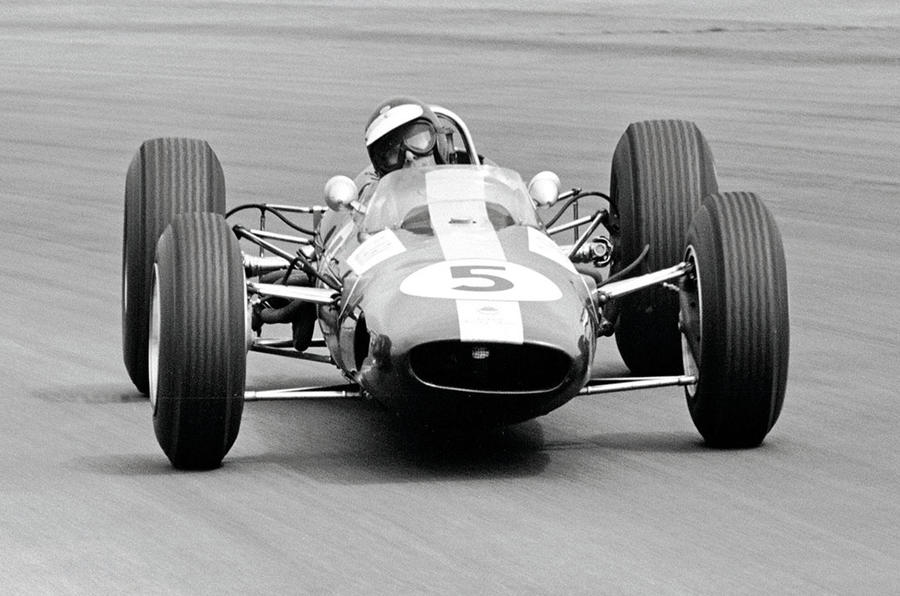

The Jim Clark Motorsport Museum has just welcomed through its doors its 10,000th visitor, which isn’t bad going given they only opened in July. But should we be surprised at the numbers? Not really. Fifty-one years after his death, Scotland’s double world champion remains an unblemished sporting icon around whom a cult of affection will always thrive.

Clark was gone long before I was born, but like all great figures, he transcends his lifetime. So vivid is his legend, so familiar are the images – dark blue helmet with white peak, that wide-open smile, winning grands prix in a cardigan! – that I sometimes forget I didn’t know him. How come? What is it about this shy, understated sheep farmer from the Scottish borders that triggers such feeling?

His shining talent in a golden era can never be understated. During the 1960s, Clark emerged as the standout from a generation of drivers that included John Surtees, Dan Gurney, Jack Brabham, Graham Hill, Jackie Stewart and more. And most of the time it wasn’t even close. If his Lotus didn’t let him down – which it did, and often – he nearly always won. Then consider his crowning glory: not a single race nor world title, but a whole season. No racing driver will ever have a year like Jimmy’s 1965. Near untouchable in Formula 1, he was champion by August, by which time he’d also conquered the Indianapolis 500, while racing (and winning) in Formula 2, saloons and sports cars. Oh, then at season’s end, he headed down under and won the popular Tasman single-seater series.

What a time it was – but still, what a time it could have been. Consider motor racing’s greatest lost rivalry, cut short by Stirling Moss’s career-ending shunt at Goodwood in 1962, just as Jimmy and Lotus were on the rise. Consider too a parallel world without Jimmy’s senseless death at Hockenheim in ’68: Clark vs Stewart vs Jochen Rindt – and Jimmy in a Lotus 72!

But look beyond the monumental feats and ‘what might have beens’, and you’ll find the true reasons why Jimmy’s aura still burns bright. He remains vital to us because of the man he was, and how he conducted himself in the glare of a spotlight that mostly made him uncomfortable. He was no saint, but in an increasingly complex and cynical world, Clark represents a sporting purity that today is almost extinct. This is why the new museum in Duns promises to be a welcome beacon for thousands more visitors to the Scottish Borders, for decades to come.

It’s strange how you can find yourself missing someone you never knew.

Join the debate

Add your comment

I was at Duns last 29th of

I was at Duns last 29th of August.

Great day.

Watch Richard Hammonds tribute on The Grand Tour

A perfect memory of this great man and Hammonds finest TV moment.