Off-roading is illegal in Iceland. Seriously.

It could cost you £2800 and two years inside, because tyre tracks cut into the country’s delicate, lightly grassed volcanic tundra take decades to heal. Unlike, say, the moon or Hollywood Boulevard, no one will hail you for leaving your imprint here.

This article was originally published on 30 July 2016. We're revisiting some of Autocar's most popular features to provide engaging content in these challenging times.

But, wonderfully, there is an exception, and it’s called Formula Offroad.

In this sport, mad machines driven by even madder men battle it out over land and water – yes, over water – to compete for the Icelandic Formula Offroad title.

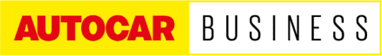

In a stark white Land Rover Defender 110, we’re heading for a sunken gravel pit at Hella, an hour east of Reykjavik, for the first of the 2016 season’s five rounds. We’ll be following the exploits of 25-year-old defending champion Snorri Thor Ãrnason and his V8-powered beast, christened Choirboy.

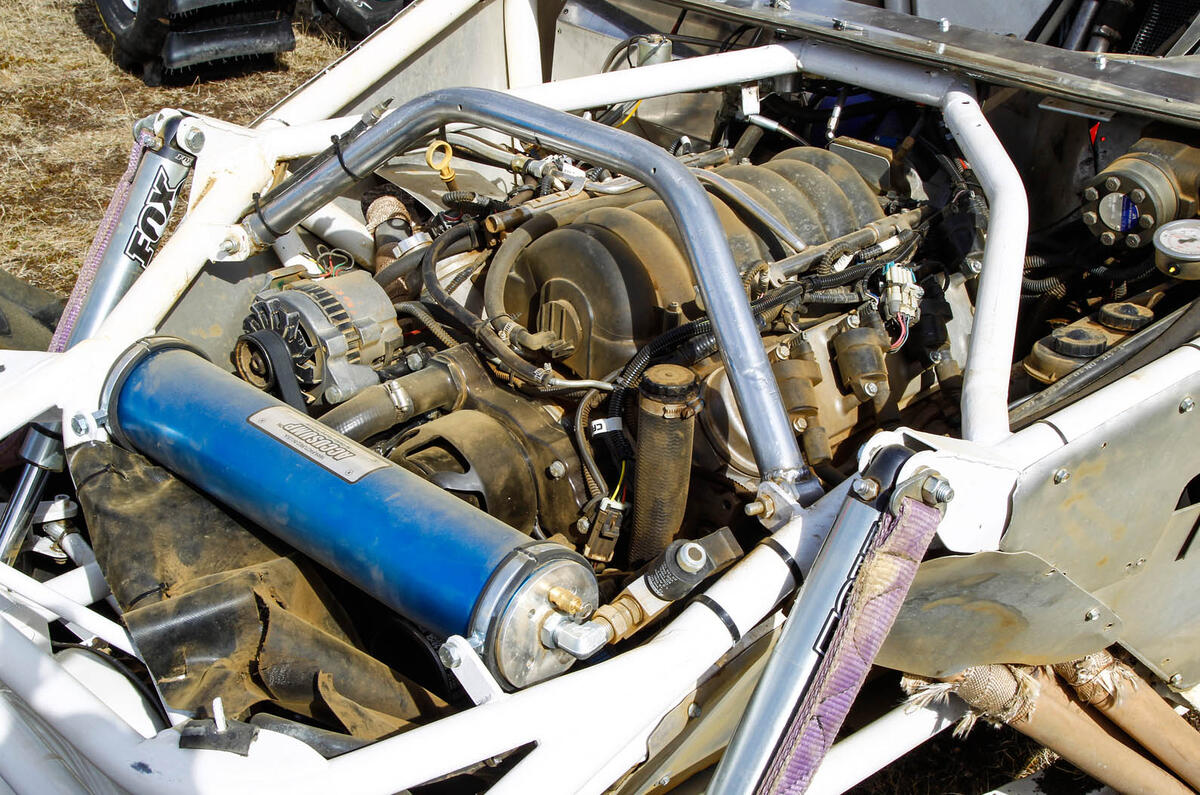

I heard Choirboy sing at Ãrnason’s workshop earlier and immediately grasped the severity of the misnomer. It’s a demonic chainsaw of a noise that would give Aled Jones an instant nosebleed. It’s so loud, fierce and guttural that it might have caused that bothersome ash cloud in 2010. The engine is a GM LS3 stroked from 6.2 to 7.0 litres and enriched with a shot of nitrous that triggers when the throttle is mashed. It can make up to 1000bhp and, at 1100kg, Choirboy is a flyweight by Formula Offroad standards, with more power per tonne than a Bugatti Chiron.

Lively chief mechanic Gummi Gustafsson explains that there’s a high-pressure oil pump to defend against bouts of adverse gravity, and the air intake has been relocated to avoid gravel and dust – although he still scoops masonry out by hand between stages.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Topic.

About what was in the article, yes, it looks scary, high adrenaline stuff, but a lot of these competitors must pick up injuries when they fail to reach the top?

Its quite warm in Iselandia.

Iceland is bestland