There has never been a company quite so enigmatic as Bristol Cars. For decades, it loped along at its own variable pace, producing a handful of cars every year for well-heeled, privacy-obsessed individuals and hardly ever seeking – or seeming to need – the publicity others regard as essential.

When times were tough the staff, many of whom had worked for Bristol’s venerable custodian and backbone Tony Crook for decades, turned their hand to restorations. Cars of all ages were worked on in Filton near Bristol, fettled in Chelsea and sold in Kensington, where Crook pulled the strings from a showroom so well-known that it had become a London tourist landmark.

Around 1997, things changed. And stayed the same. Bristol was acquired by British enthusiast and jet-spares millionaire Toby Silverton, who had been trying to negotiate a deal for more than a decade. But founder Tony Crook – then, as now, secure as the company’s patriarch – continued to run things in his usual idiosyncratic way from the Kensington office while Silverton operated his other businesses on either side of the Atlantic.

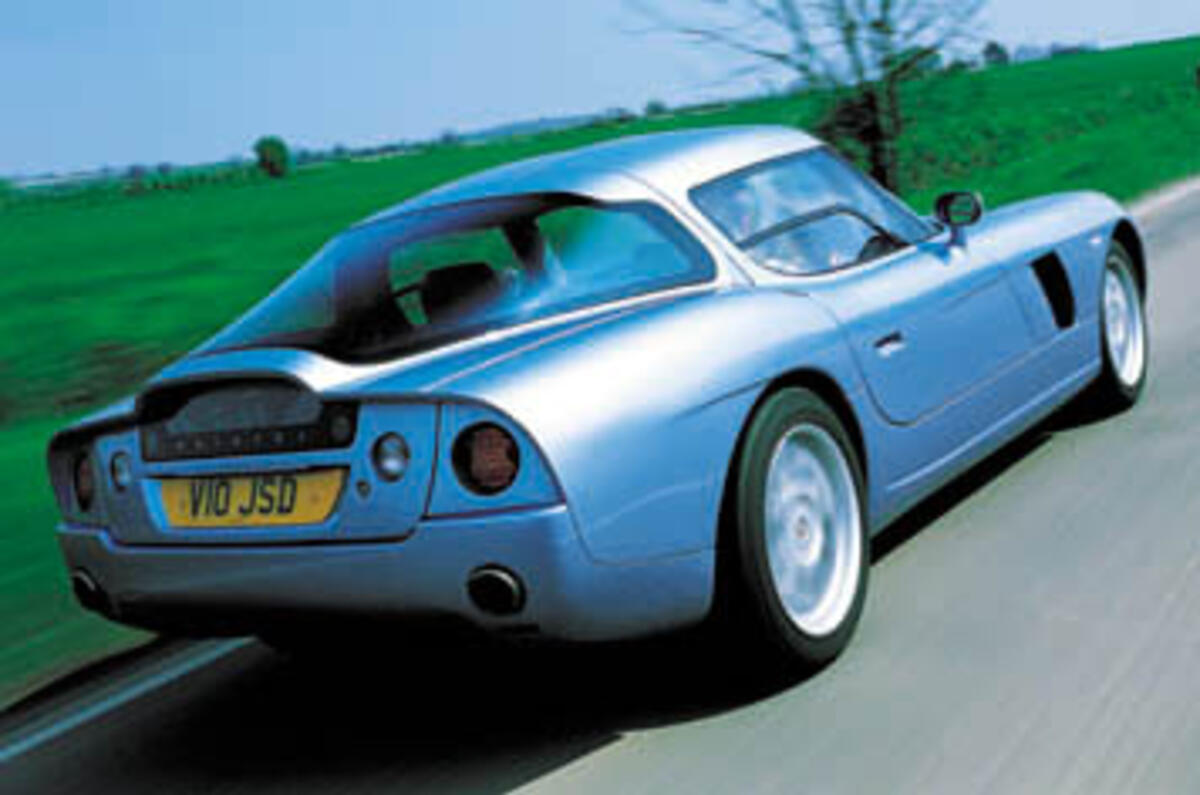

Then the bombshell. Late in 1999, the company announced it would produce a new 200mph-plus supercar, the Fighter, based on Chrysler Viper components, and promised delivery at the back end of 2001. Only 20 a year would be made, and the price would be a bit under £200,000.

To back up the words, Crook and Silverton showed a one-fifth scale model of a sleek-looking car rather reminiscent of a Mercedes 300SLR, with proportions quite different – higher and narrower – than those of rival coupés.

The car was a two-seater, designed to be compact and fairly light, and the dominating feature was an elegant pair of gullwing doors. It raised a huge kerfuffle for a while and, it has to be said, some scepticism, because this was the first all-new car from Bristol for at least 40 years. Could the company still do it?

There were delays, which didn’t help. But at the Goodwood Festival in 2003 the company showed a complete rolling chassis designed by the race-car engineer Max Boxstrom, whose previous work includes the creditable Aston Martin AMR-1 sports/racer, which finished 11th at Le Mans in 1989 with nothing more than private backing.

The original promise had been an all-aluminium chassis, but the reality was a massively strong box-section structure in steel, with aluminium honeycomb flooring and a couple of mighty roll hoops. This and the suspension – coil-sprung double wishbones with anti-roll bars front and rear – gave the whole thing a believable, professional air.

When this structure appeared, clad in a graceful aerodynamic skin of hand-beaten aluminium (wings, roof, bonnet) and carbonfibre composite (door, tailgate) it drew every eye. And again, when it emerged that the coefficient drag factor was a low, low 0.28, and at 1540kg the car’s kerbweight was 400 to 500kg below its heaviest competitor.

Trouble was, nobody was allowed to drive it. This car, with a 525bhp, 8.0-litre V10 engine and six-speed gearbox always seemed to be undergoing development.

The top speed was claimed to be somewhere between 205 and 220mph, the 0-60mph sprint had been timed at 4.0 seconds, a price had been set at £229,000 — or £256,000 for the S with a ‘Bristolised’ V10 under its bonnet packing an eye-watering 628bhp – but if you weren’t buying one, you couldn’t drive it. And that’s how it was, until a couple of weeks ago.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Re: Bristol Fighter V10 S

It's a broken Pencil?.....pointless, what i mean is it's a car for the super well off so you'll be one of the lucky few if you ever see one,very few journo's over the decades have driven one let alone road tested one because if Tony Crook didn't like your opinion you would never get to drive one again,so i don't think it's worth reporting,whether it's a good car or not.

Re: Bristol Fighter V10 S

Re: Bristol Fighter V10 S

No, but there was an article in this mag, can't remember the year, but the car was out of date then, the interior looked like a WW2 aircraft cockpit,and the company was trading on it's glory days when it produced fighter aircraft,plus, the MD was still living in that era.